On November 8, 2016, the prime minister Narendra Modi announced his government’s decision to demonetise Rs 500 and Rs 1,000 notes, to an unsuspecting nation. The decision came into effect from the midnight between November 8 and November 9, 2016, and suddenly rendered 86.4 per cent of the nation’s currency in circulation, useless.

It’s been six months since then and more than four months since December 30, 2016, the last date for depositing the demonetised Rs 500 an Rs 1,000 notes, into bank accounts. But even after this period as far as the government is concerned, a few basic points remain.

a) How much demonetised money finally made it into bank accounts? When demonetisation was first announced, this number was shared regularly. Nevertheless, the last announcement on this front from the Reserve Bank of India(RBI) came on December 13, 2016. As of December 10, 2016, Rs 12.44 lakh crore of demonetised currency had made it back into the banks.

Given that Rs 15.44 lakh crore worth of currency notes had been demonetised, nearly 80.6 per cent of the currency had found its way back into banks, nearly three weeks before the last date to deposit demonetised notes into bank accounts.

Neither the Reserve Bank nor the government has told the nation how much money eventually made it back into the banks. This is an important question and needs to be answered.

b) The initial idea behind demonetisation was to curb fake currency notes and eliminate black money.

As far as fake currency goes the minister of state for finance Arjun Ram Meghwal told the Lok Sabha in early February 2017 that the total number of fake notes deducted in the currency deposited into banks after demonetisation stood at 2.46 lakhs. This amounted to a total value of Rs 19.5 crore.

As mentioned earlier, the total value of demonetised notes had stood at Rs 15.44 lakh crore. Given this, the proportion of fake notes deducted is almost zero and can be ignored. Hence, as far as detecting and eliminating fake notes was concerned, demonetisation was a total flop.

How did it do as far as eliminating black money is concerned? The hope was that the black money held in the form of cash will not make it back into the banks, as people wouldn’t want to get caught by declaring it. But by December 10, 2016, more than four-fifth of the demonetised notes had already made it back into the banks. Since then the government and the RBI have not given out any fresh numbers. It’s surprising that it has been more than four months since December 30, 2016, and this number is still not out in the public domain.

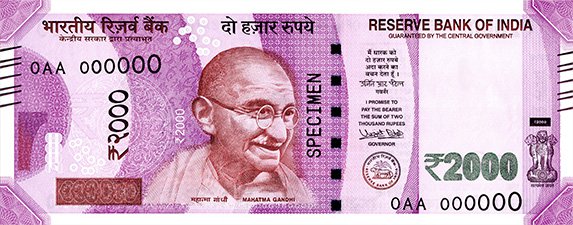

Also, it is important to point out here: “High denomination notes are known to facilitate generation of black money. In this connection, it may be noted that while the total number of bank notes in circulation rose by 40% between 2011 and 2016, the increase in number of notes of Rs.500/- denomination was 76% and for Rs.1,000/- denomination was 109% during this period.”

If high denomination notes facilitate generation of black money, then why replace Rs 1,000 notes with Rs 2,000 notes. Given that a Rs 2,000 note is twice the value of a Rs 1,000 note, it makes black market transactions even more easier. It also makes storage of black money in the form of cash easier, given that it takes less space to hide the same amount of money.

Again, this is a basic disconnect in what the government planned to achieve through demonetisation and what it eventually did. No effort has been made to correct this disconnect.

c) The government has still not offered a good explanation of what prompted it to demonetise. There has been no similar decision taken by any other country in a stable financial situation like India currently is, in the modern era. The best that the government has done is blamed it on the RBI. As Meghwal told the Lok Sabha in early February 2017: “RBI held a meeting of its Central Board on November 8, 2016. The agenda of the meeting, inter-alia, included the item: “Memorandum on existing banknotes in the denomination of Rs 500 and Rs 1000 – Legal Tender Status.””

Anybody who has studied the history of the RBI would know that the RBI would never take such an extreme step without extreme pressure from the government.

d) Other than eliminating black money and fake currency notes through demonetisation, in the aftermath of demonetisation, the government wanted to promote cashless transactions. As Modi said in the November 2016 edition of themann ki baat radio programme: “The great task that the country wants to accomplish today is the realisation of our dream of a ‘Cashless Society’. It is true that a hundred percent cashless society is not possible. But why should India not make a beginning in creating a ‘less-cash society’? Once we embark on our journey to create a ‘less-cash society’, the goal of ‘cashless society’ will not remain very far.”

How are things looking on that front? Look at the following table. It shows the volume of digital transactions over the last few months.

| Month | Volume of digital transactions (in million) |

| Nov-16 | 671.5 |

| Dec-16 | 957.5 |

| Jan-17 | 870.4 |

| Feb-17 | 763.0 |

| Mar-17 | 893.9 |

| Apr-17 | 843.5 |

Source: Reserve Bank of India

While digital transactions picked up in December, they have fallen since then. The total number of digital transactions in April 2017 is higher than it was in November 2016. Nevertheless, it is worth asking, whether this jump of 25 per cent was really worth the trouble of demonetisation.

e) Falling digital transactions since December 2016 tell us that cash as a mode of payment is back in the system. There is another way this can be shown. Between November 2016 and February 2017, banks barely gave out any home loans. During the period, the banks gave out home loans worth Rs 8,851 crore. In March 2017, they gave out total home loans of Rs 39,952 crore, which was 4.5 times the home loans given out in the previous four months. It also amounted to 35 per cent of the home loans given out during the course of 2016-2017.

A major reason why people weren’t taking on home loans between November 2016 and February 2017 was demonetisation. There simply wasn’t enough currency going around. With this, the real estate transactions came to a standstill because without currency it wasn’t possible to fulfil the black part of the real estate transaction. Those who owned homes (builders and investors) were not ready to sell homes, without being paid for a certain part of the price, in black.

By March 2017, nearly three-fourths of the demonetised currency was replaced. This basically means that by March 2017, there was enough currency in the financial system for the black part of the real estate transactions to start happening all over again. Also, the Rs 2,000 note makes this even more convenient.

To conclude, six months after the declaration of demonetisation it is safe to say that demonetisation has failed to achieve what it set out to achieve i.e. if it set out to achieve anything on the economic front.

The column originally appeared on Firstpost on May 9, 2017