Vivek Kaul

Over the last few days my mother and her sister have been complaining about how the price of the 10 kg bag of rice that they buy has gone up by 17% in just over a couple of month’s time.

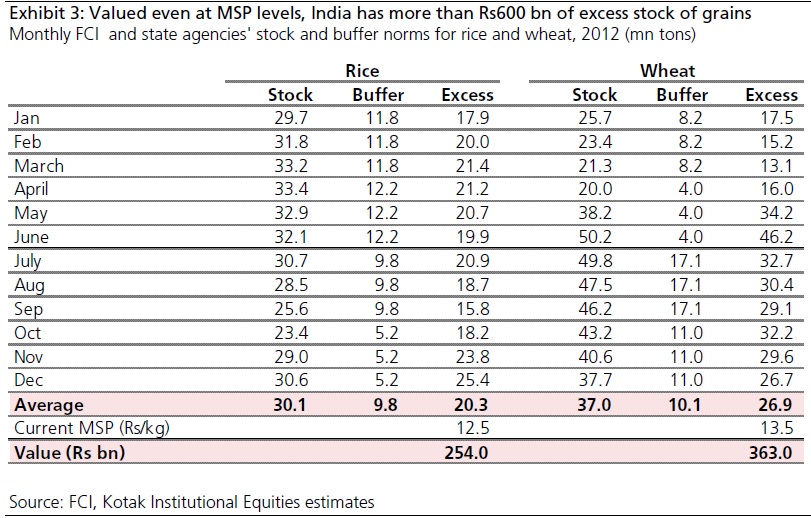

Now contrast this with what Akhilesh Tilotia of Kotak Institutional Equities Research writes in the GameChanger Perspectives report titled Putting the mountain of grains to use (Released on March 5, 2013). “India can raise more than Rs60,000 crore if it prunes its inventory of food grains: an excess 20 million tons of rice and 26 million tons of wheat (without accounting for procurements to be made this year),” writes Tilotia. (The table shows the numbers in detail).

As the above table shows the government currently has an excess rice stock worth around Rs 25,400 crore and an excess wheat stock worth Rs 36,300 crore, or more than Rs 60,000 crore in total. These numbers have been arrived at by taking into account the MSP of rice at Rs 12.5 per kg and the MSP of wheat at Rs 13.5 per kg and multiplying them with the excess stocks. What the table also tells us is that the government currently has an excess rice stock of nearly 2 times the buffer and an excess wheat stock of nearly 2.7 times the buffer.

The government sets a minimum support price(MSP) for wheat and rice. Every year the Food Corporation of India (FCI), or a state agency acting on its behalf, purchases rice and wheat at MSPs set by the government. The “supposed” idea behind setting the MSP much and that too much in advance is to give the farmer some idea of how much he should expect to earn when he sells his produce a few months later. FCI typically purchases around 15-20 percent of India’s wheat output and 12-15 percent of its rice output, estimates suggest.

At least this is how things are supposed to work in theory. But most government motives have unintended consequences. With an assured price more rice and wheat lands up with the government than it distributes through the public distribution system. Also with FCI obligated to purchase what the farmers bring in, its godowns overflow and at times the wheat and rice are dumped in the open, leading to rodents feasting on the crop.

On the other hand the way things currently are it helps the farmer as he has an assured buyer in the government for his produce. But what it also does is it pushes up prices of rice and wheat everywhere else, as more of it lands up in the godowns of FCI and not in the open market.

The procurement also adds to the food subsidy. The government pays for all the rice and wheat that the farmer brings to it and then lets a lot of it rot. The government currently has nearly 67 million tonnes of rice and wheat in stock. Of this nearly 47 million tonnes is excess.

Tilotia expects the rice and wheat stock of the government to go up to 100 million tonnes by the time this harvest season gets over. As he writes “After the current harvest season, Indian granaries will stock about 100 million tonnes of wheat and rice…A high inventory comes with a heavy carrying cost, which the FCI estimates at Rs6.12 per kg for year-end September 2014: At 100 million tons, this will cost India Rs 60,000 crore a year (forming most of its food subsidy bill).”

A higher food subsidy bill adds to the fiscal deficit and which as writers Firstpost regularly keeps discussing has huge consequences of its own. Fiscal deficit is the difference between what a government spends and what it earns.

In fact, the United States of America had a similar policy in place in the aftermath of The Great Depression which started in 1929, on a number of agri-commodities like wheat, tobacco, cotton etc. The government offered a support price to farmers. This support price had unintended consequences over the years, especially in case of wheat.

As Bruce Gardner writes in the research paper “The Political Economy of U.S.Export Subsidies for Wheat” (quoted by Tilotia) “The traditional means of price support is a governmental agreement, through its Commodity Credit Corporation (CCC), to buy wheat at the support price. This programme periodically led to governmental acquisition of large stocks which were costly to store and for which markets did not exist at the support price level.”

As is happening in India right now the American government ended up buying more and more wheat, of which it had no use for, especially at the price it was paying for it. The farmers had an assured buyer in the government and they went around producing more wheat than before.

This resulted in excess stocks with the American government. Over the years this excess wheat was exported at a subsidised rates. As Gardner writes “The subsidy ranged from 5 to 30 percent of the price of wheat, depending on world and U.S. market conditions in each year.” A lot of wheat was also donated under the Agricultural Trade and Development Act of 1954 ( better known as P.L. 480) of which India was a huge beneficiary in the late 50s and early 60s till Lal Bahadur Shastri initiated the agricultural revolution.

Gradually the wheat acreage, or the area over which wheat was planted, was also reduced in the United States. This meant that the farmers had to keep their land idle and not plant wheat on it. “Acreage allotments…were reintroduced in 1954 and reduced planted acreage by about 18 million acres (from 79 million in 1953 to an average of 61 million in 1954-56). Each producer had to stay under the farm’s allotment in order to be eligible for price support loans. In 1956 the Soil Bank program was introduced. It paid wheat growers about $20 per acre (roughly market rental rates) to idle an average of 12 million more acres (20 percent of preprogram acreage) in 1956-58,” writes Gardner.

India seems to be heading on the same path if the current policies don’t change. As Tilotia writes “India’s inventory is concentrated in the north-western states of Punjab and Haryana, which store 36 million tons of its 66 million tons of stock. Given the large procurement expected from these states again this year (though Madhya Pradesh may better Haryana in wheat procurement this year, especially given state elections), this imbalance can worsen.”

Interestingly, the government can use this excess inventory of rice and wheat to control inflation and at the same time bring down its fiscal deficit. The government currently has rice and wheat worth in excess of Rs 60,000 crore. On the other hand it also has a disinvestment target of Rs 54,000 crore for the next financial year (i.e. the period between April 1, 2013 and March 31, 2014). The government hopes to earn this amount by selling stakes it holds in public sector units to the public.

Along similar lines the government can try selling the excess rice and wheat that it currently holds in the open market. This will help control food inflation with the excess government stock hitting the market. Food forms around 43% of the consumer price inflation number and so if food inflation comes down, the consumer price inflation is also likely to come down.

The challenge of course in doing this is two fold. The first being moving grains from Punjab, Haryana where more than half the inventory lies. The second is to ensure that the market prices of rice and wheat don’t collapse.

Also the current MSP system is not working. If the idea is to pay the citizens of this country to improve their living standards, the government may be better off paying them in cash, rather than paying them in this roundabout manner that creates inflation. This is simply because the current system drives up the price of food for everyone else and it doesn’t necessarily always benefit the farmers. The middleman continue to make the most money.

As Tilotia puts it “If such a payment indeed needs to be made, there is no point in raising prices for all in the system by adding it to the price of the grain: Simply pay the farmer whatever support you want to pay him/her. India is reaching a situation where, by using UID it would be able to send payments to farmers directly. Maybe it is time to re-couple wheat and rice prices with global prices – that can meaningfully reduce inflation in India.”

The article originally appeared on www.firstpost.com on March 6,2013.

(Vivek Kaul is a writer. He tweets @kaul_vivek)

Akhilesh Tilotia

Adi Godrej’s Marie Antoinette moment: Indian farmer should invest in stocks

Vivek Kaul

“Qu’ils mangent de la brioche” is a French phrase which means “let them eat cake” in English. It is often attributed to the French Queen Marie Antoinette. She had apparently said this to peasants when she came to know that they had no bread to eat.

There is no record that the Marie Antoinette, wife of Louis XVI ever uttered these words. But the myth has held even after all these years. And the story does make a broader point about the rich often having no idea about the state of the poor in their country.

A good example of this is Adi Godrej, the current president of the Confederation of Indian Industry (CII), who recently had his Marie Antoinette moment. In a recent interview to the Tehelka magazine Godrej suggested that the Indian farmers should sell their land and invest the money they get in stocks and mutual funds.

“If India has to become a developed country, you cannot have the livelihood of hundreds of millions of people depending on agriculture. They have to move on. They have to move into industry, into services. That’s how you develop a country. That has happened in every country,” Godrej said.

He further went onto add that the money that the farmers get by selling their land should be invested in stocks, so that it does not run out soon. “Why should it run out soon? It can be invested. It can be made into a much bigger value than land. Land has the lowest appreciation of all assets. The best investments are in stocks. Somebody should advise them to invest it in mutual funds so their wealth will rise faster,” Godrej said.

Let’s try and examine these statements in a little more detail. Agriculture contributes around 14% of India’s gross domestic product (GDP). This has fallen dramatically since 2004-2005, when it used to contribute around 19% of India’s GDP. At the same time it employs around 58.4% of India’s population. (Source: http://www.india.gov.in/sectors/agriculture/index.php).

So 58.4% of India’s population contributes around 14% of India’s GDP. It need not be said that this is a terribly inefficient way of working. Ruchir Sharma of Morgan Stanley calls this “a disturbing tendency of the farmer to stay on the farm” in his book Breakout Nations.

The contribution of agriculture to the overall GDP is expected to continue falling in the years to come. A calculation carried out by the Planning Commission shows that the contribution of agriculture to the total GDP would fall to as low as 7% by 2025-2026. This calculation assumes a fairly optimistic growth of 4% per year in agriculture GDP. At a growth rate of 2%, agriculture’s contribution to overall GDP by 2025-2026 is expected to be at 5.2%.

In making these calculations the Planning Commission assumes that the overall GDP will keep increasing by 8% every year, which is a very optimistic assumption to make given the current state of affairs. (You can see the calculations here).

But even assuming a 4% growth rate for agriculture and just 6% for overall GDP, the contribution of agriculture to the overall GDP can be expected to fall to around 9.8% (This is my calculation and not of the Planning Commission),from the current 14%.

So theoretically the contribution of agriculture to GDP will fall in the coming years. This can be said with utmost certainty. This means that other sectors of the economy like services and industry will grow at a much faster rate. Hence, it makes sense for farmers to sell their land, move on from farming and move onto other sectors of the economy.

And that’s what Godrej suggested in his interview to Tehelka. But even after that if the Indian farmer is unwilling to sell his land there must be some reason to it.

Akhilesh Tilotia of Kotak Institutional Equities has done some interesting analysis on this. As he points out in a recent report “a farmer makes about Rs30,000 per acre a year (assuming two crops a year) if he grows staples like wheat or paddy. One can argue that the price at which a farmer should be happy to sell the land would be at Rs 2-3 lakh an acre (or seven to ten times his annual income from the land).”

But then money is not the only issue at hand. As Tilotia writes “However, there is an element of sustainability and certainty for the farmer from agriculture and he suffers from a lack of skill to get him or his family employed elsewhere (either in the plant coming up or in the urban services industry): All this means the farmer is looking at farming as a means of livelihood and not from a pure ‘return on capital’ perspective.”

The average farmer does not want to sell out because he is not skilled enough to do anything else. A lot of them are still uneducated given that the effective literacy rate in India is around 74%.

Also the average land holding of an Indian farmer is around 1.4 hectares (one hectare equals around 2.5acres).This is very small and even if he sells, he is unlikely to make much money from it. The right to property is not a fundamental right in India. And over the years the government of India has acquired land forcibly from the citizens of this country at rock bottom prices. This is an impression that cannot be gotten rid off overnight. And hence the Indian farmer is unwilling to sell his land.

But things have gradually started to change as the government has started to offer reasonable prices for acquiring land. “National Highway Authority of India’s cost of acquisition of land was Rs 25lakh per acre in Financial year (FY) 2011…It acquired 8,533 hectares in FY2011, up from 3,120 hectares in FY2009. In FY2012, NHAI expects to acquire 12,000 hectares. The size of land acquisition is up 4 times over the past four years when the going narrative has been that land acquisition has been made impossible in India,” writes Tilotia.

So just saying that the Indian farmer needs to move is not enough. The conditions have to be right for him. He needs to have the skill-set to move on, which he currently doesn’t. Very little attempts are made by the government to rehabilitate those whose land is acquired. And more than that, the farmer needs to be offered the right price, which he wasn’t being offered till very recently.

The other suggestion that came from Godrej was that farmers should invest in stocks and mutual funds. It would be nice if he goes through a November 2011 presentation made by the

by the India Brand Equity Foundation (IBEF). This shouldn’t be difficult given that IBEF is a trust established by the Ministry of Commerce with the CII. As pointed out earlier Godrej is the President of the CII.

The presentation throws up some interesting facts: A few of them are listed below:

– Despite healthy growth over the past few years, the Indian banking sector is relatively underpenetrated.

– Limited banking penetration in India is also evident from low branch per 100,000 adults ratio – – Branch per 100,000 adults ratio in India stands at 747 compared to 1,065 for Brazil and 2,063 for Malaysia

– Of the 600,000 village habitations in India only 5 per cent have a commercial bank branch

– Only 40 per cent of the adult population has bank accounts.

Given this it is unlikely that many Indian farmers have banks accounts. How can those who don’t even have bank accounts be expected to invest in the stock market? Also the stock returns in India even over the long term haven’t been great. The BSE Sensex over a period of 20 years has given a return of 8.9% per year. And even these returns haven’t been guaranteed.

So the first thing that Indian farmers should be doing is opening bank accounts.

Also, how can farmers be expected buy stocks when even the Indian middle class, which makes much more money than the Indian farmer has stayed away from investing in stocks. And there are genuine reasons for it.

As Shankar Sharma of First Global told me in a recent interview I did for the Daily News and Analysis(DNA): “We see too much of risk in our day to day lives and so we want security when it comes to our financial investing. Investing in equity is a mindset. That when I am secure, I have got good visibility of my future, be it employment or business or taxes, when all those things are set, then I say okay, now I can take some risk in life. But look across emerging markets, look at Brazil’s history, look at Russia’s history, look at India’s history, look at China’s history, do you think citizens of any of these countries can say I have had a great time for years now? That life has been nice and peaceful? I have a good house with a good job with two kids playing in the lawn with a picket fence? Sorry boss, this has never happened.”

This statement is as valid for the Indian farmer as it is for the Indian middle class. And so it’s time Adi Godrej realised that things in the real India are a little different. Marie Antoinette

may not have said “let them eat cakes” but Adi Godrej surely did.

(The article originally appeared on www.firstpost.com on September 12,2012. http://www.firstpost.com/business/adi-godrejs-marie-antoinette-moment-indian-farmer-should-invest-in-stocks-452776.html)

(Vivek Kaul is a writer and can be reached at [email protected])