Summary:

There must be some kind of way outta here

Said the joker to the thief

There’s too much confusion

I can’t get no relief.

— Bob Dylan, All Along the Watchtower.

India’s midnight tryst with the Goods and Services Tax (GST) is a little over three years old and is looking more and more like a bad joke which, we brought upon ourselves.

The state of GST takes me back to the last thirty minutes of several Priyadarshan comedies, where everyone is running after everyone else and no one knows what is really happening. (Actually, it can also compared to the ending of the wonderful comedy Andaz Apna Apna).

In reel life, all this confusion has the audience in splits. In real life, those going through the experience feel like they are a part of surreal black comedy.

Yesterday, the finance minister Nirmala Sitharaman said that the covid-19 pandemic was an act of god and that would impact GST collections negatively. An act of god is essentially a natural hazard which is beyond human control, something like an earthquake or a tsunami for that matter. No one can be held responsible for it.

The act of god has led to a situation where the GST collections have nose-dived. This is hardly surprising given that private-consumption has come down over the last few months. Also, by characterising the fall as an act of god, the central government doesn’t want to be held responsible for the fall in GST collections.

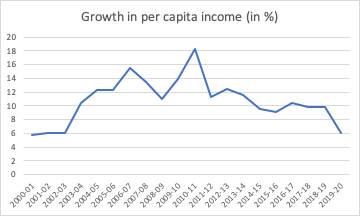

Nevertheless, it needs to be said here that GST collections weren’t doing well even before covid-19 struck. Let’s take a look at the growth/fall in GST collections between August 2018 and February 2020, before the covid pandemic struck.

All is well?

Source: Centre for Monitoring Indian Economy.

The above chart clearly shows that the growth in GST collections had been falling since early 2019 though it did recover a little since late last year, before stabilizing at half of the peak growth. In November 2018, the growth in GST collections was 16.5%. In February 2020, it was at 8.3%.

The point here being that the growth in GST collections had slowed down since early 2019. It picked up again in late 2019, thanks to a cap on the input tax credit that certain businesses could take. Festival season sales also helped.

This slower growth in GST collections was a reflection of a broader economic slowdown, for which the botched up implementation of GST was also hugely responsible. Of course, the spread of the covid pandemic has only made the situation much worse, with GST collections falling between March and July.

In a normal scenario, a fall in tax collections would mean lower expenditure by the government. But the situation that prevails is nowhere near normal. With private consumption falling, the governments (states and central) are expected to continue spending money, in order to keep the economy going. Also, state governments are at the forefront of fighting the epidemic and they need money to do that.

The GST collections are split between the central government and the state governments. One of the carrots that the central government had offered to the states in a bid to make GST acceptable and to hasten India’s midnight tryst with GST, was a promise of a compensation if the GST revenues did not grow by 14% from one year to the next. The GST(Compensation to States) Act, guarantees state governments a revenue protection of 14% for the first five years of GST.

Of course, it doesn’t take rocket science to understand that GST revenues will contract in 2020-21, the current financial year. Hence, as per the GST(Compensation to States) Act, state governments need to paid a compensation by the central government.

As per the law, a compensation needs to be paid to state governments every two months. In fact, the compensation due to states for the period April to July 2020, stands at Rs 1.5 lakh crore.

This money comes from the compensation cess which is levied on both sin and luxury goods. The trouble is that like the overall GST collections, the growth in collections of the compensation cess had been falling through most of 2019. This can be seen in the following chart.

To sin or not to sin?

Source: Centre for Monitoring Indian Economy.

In June 2020 and July 2020, the collections of compensation cess fell by 9.4% and 15%, respectively. It needs to be said that even during an economic slowdown or a contraction, the consumption of sin and luxury goods does not fall at the same pace as the overall consumption. But despite that, the compensation cess collected in 2020-21 will not be enough to pay state governments to ensure a 14% growth in overall GST earned.

The shortfall in GST collections as per the central government is expected to be at Rs 2.35 lakh crore. It has said that this shortfall cannot be paid for through the consolidated fund of India, which is a repository for all the money earned by the central government through taxes as well as the money it borrows.

Basically, the central government after promising a 14% growth protection to states on GST, has come back and told them, hey, now that we are in trouble, you are on your own. It reminds me of an old line in buses in North India, sawari apne samaan ke khud zimmedar hai (the travellers are responsible for what they are carrying). The joke, the way the drivers of these buses drove, was, sawari apni jaan ke bhi khud zimmedar hai (the passengers are also responsible for their lives). This is the kind of joke that the central government has just cracked on state governments. This is black humour of the finest kind, which you won’t even see in an Anurag Kashyap movie.

In order to fulfil the gap, the options offered to the state governments by the central government are: 1) To borrow Rs 97,000 crore at a reasonable rate of interest from a special window at the Reserve Bank of India. The Rs 97,000 crore number is an estimate of GST loss due to implementation issues. 2) To borrow the entire gap of Rs 2.35 lakh crore. These options are only for 2020-21. The states can repay the money in the years to come by using the GST compensation cess they receive in the years to come.

This leads to a few points:

1) The central government basically sold the state governments a dummy in promising a 14% growth in GST collections. A narrative was created, it was marketed and then the constituents of the narrative were abandoned.

2) The state governments were also responsible for this to some extent given their resistance to the original law. Also, the central government was in a hurry to ensure India’s midnight tryst with GST, in order to create a narrative.

3) It is easier for the central government to borrow than for the states to do so. It seems here that the central government doesn’t want to spoil its fiscal deficit number any further than it already will this year. Fiscal deficit is the difference between what a government earns and what it spends.

Nevertheless, whatever be the case, the total government borrowing (centre + states) is bound to go up. So, I really can’t understand what is the fuss around the central government borrowing more. Also, with the GST in place, the ability of state governments to tax more is rather limited. Their main taxes on alcohol, real estate, petroleum products and vehicles, have already taken a huge beating this year.

4) It will be interesting to see the legal logic being used by the central government to take this stance. From what I understand, the GST Council and the central government are being considered separate entities (Maybe some lawyer can explain this in simple English).

5) If the state governments borrow from the market, how is it going to impact bond yields?

6) Also, the compensation cess on luxury and sin goods, will now have to be extended beyond 2022 and this will not go down well with businesses, which are already struggling.

7) There is bound to be in increase in compensation cess on some luxury and sin goods during this financial year. That remains the easiest way for the government to increase tax revenues. Also, I sincerely hope the GST Council doesn’t start increasing tax rates on normal goods in a bid to shore up revenues (Governments and government bodies have a tendency to do that).

Of course, the move hasn’t gone down well with state governments. Sushil Modi, the deputy chief minister of Bihar told this to the Press Trust of India, even before the GST Council meet: “It is the commitment of the central government to compensate the states for the shortfall in GST collections. It’s true that it is legally not binding on the Centre, but morally, it is.” Modi belongs to the BJP.

West Bengal finance minister Amit Mitra said: “The question is who should borrow. The Centre… can get a better rate and has more debt servicing capacity.” The finance minister of Delhi, Manish Sisodia, accused the Centre of “betraying” federalism by “refusing” to pay GST compensation to states.

As stated earlier, these options are only for 2020-21. What happens next year? With covid-19 pandemic continuing, the negative economic impact of this might be felt next year as well. The states have a week’s time to get back to the GST Council.

Of course, until then and even beyond, all the confusion will prevail. As I said, the entire scenario now looks like the last thirty minutes of a Priyadarshan movie, where everyone is going after everyone else, and no one knows what is actually happening. The irony is that this is in real life and not something to laugh at. But then when a government talks about an act of god to wriggle out of something that it clearly promised to many other governments, what else can one do anyway but laugh in pain.

There’s has got to be some difference between the government of the world’s largest democracy and an insurance company?