Vivek Kaul

Vivek Kaul

Sometime in the mid 1980s, I vaguely remember spending a few days with my family, in one of the many small coal producing towns that dot what is now known as the state of Jharkhand. As was common in those days, we had hired a VCR and had decided to go on a movie watching spree.

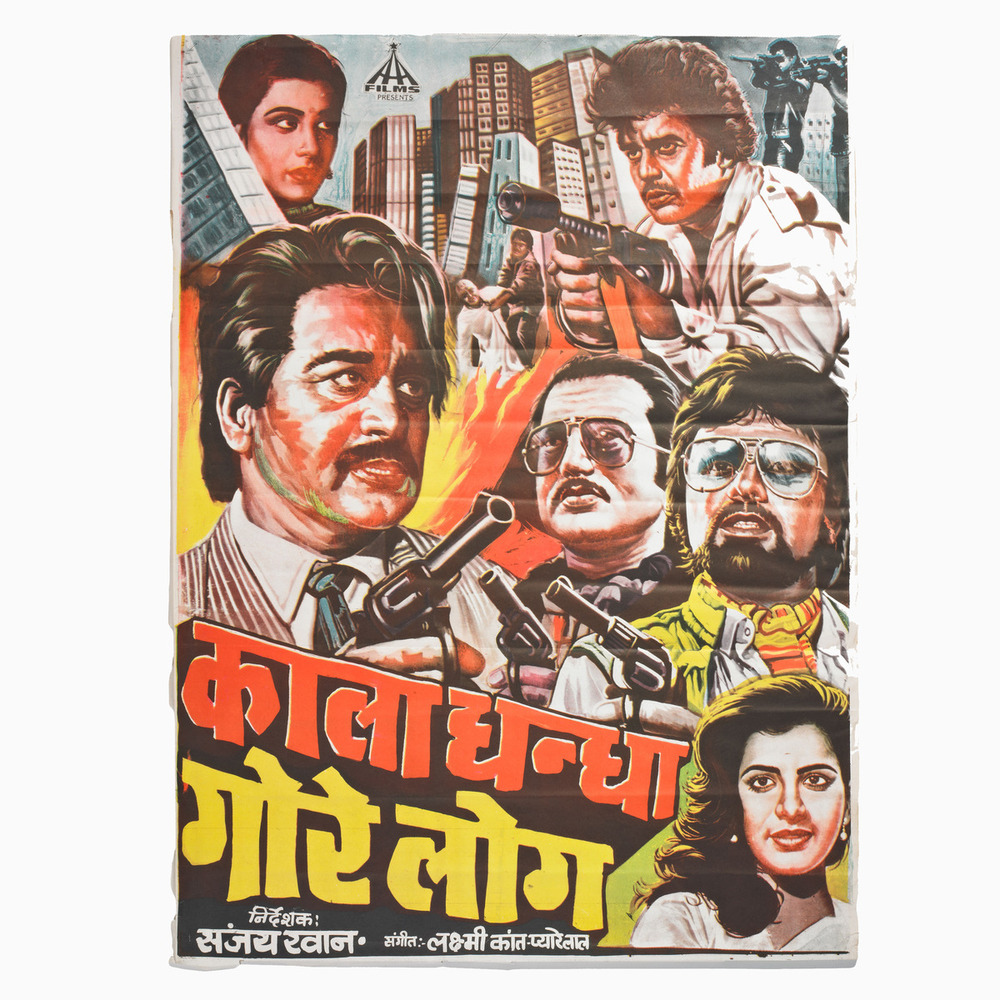

One of the movies on the list was Kaala Dhandha Gore Log. The movie was directed by Sanjay Khan. That is the only bit about it that I still remember. I don’t know why, but I found the title of the movie very fascinating and was really looking forward to watching it.

But the adults in the family threw a spanner in the works and banned us “kids” from watching the movie, without really going into the reasons for it. Around three decades later I can speculate as to why we weren’t allowed to watch the movie.

I guess the movie must have had a few scenes with the heroine mouthing the most famous cliché of the eighties,“mujhe bhagwan ke liye chhod do,” or it must have had songs we now call “item numbers”.

Those were days when cable television hadn’t come to India (that would happen only in late 1991, early 1992). Middle class India still hadn’t discovered The Bold and the Beautiful or Santa Barbara for that matter, two shows that went a long way in Indian parents becoming a lot more liberal in deciding what their kids could watch on television.

For some reason the title of the movie has always stayed in my mind, and I have speculated now and then, on its possible storyline. As the title of the movie suggests, the story could possibly be about businesses run by white people (meaning foreigners) which throw up black money.

Three decades later, reel life seems to have turned into real life. There is a great belief in this country that all of the black money generated over the years is now with foreigners. It has been transferred into foreign banks operating out of tax havens. The prime minister Narendra Modi has promised to get the money back.

In an earlier piece I had explained why getting this money back is not a feasible proposition, even though it might sound possible. And a better thing to do would be to simply concentrate on unearthing all the black money that is there in the country. I had also said that a lot of black money which has gone abroad over the years is possibly now being round-tripped to India, given that the chances of earning a good return are better in India.

Nevertheless, there are two questions that arise here? First, why has the black money problem been allowed to become so huge? Second, will the politicians choose to do anything about it? Let me answer the second question first.

Political analyst Mohan Guruswamy shared some very interesting data in a recent column in The Asian Age. Between 2004-05 and 2011-12, national political parties collected Rs 435.87 crore as donations. Of this the Bhartiya Janata Party received Rs 192.47 crore from 1,334 donors and the Congress Rs 172.25 crore from 418 donors.

Corporates made 87% of these donations. Interestingly, over and above this, the parties received donations from unknown contributors as well. The Congress party received a total of Rs 1,185 crore in three financial years (2007-08, 2008-09, 2009-10) and the BJP received around Rs 600 crore during the same period.

It is worth remembering that in the period between 2004-05 and 2011-12, there were two Lok Sabha elections and many elections to state assemblies. It doesn’t take rocket science to come to the conclusion that the amount of donations declared by the political parties were clearly not enough to fight so many elections.

In fact, a study carried out by Centre for Media Studies in March earlier this year estimated that around Rs 30,000 crore would be spent during the 16th Lok Sabha elections which happened in April and May 2014. Of this total, the government would spend around Rs 7,000-8,000 crore to conduct the elections through the Election Commission and the home ministry.

The remaining amounts would be spent by the candidates contesting the elections and the political parties they belonged to. Candidates standing for Lok Sabha elections are allowed to spend only Rs 70 lakhs for fighting an election in bigger states. For other states, the amount varies from anywhere between Rs 22 lakh to Rs 54 lakh.

These amounts are peanuts when it comes to fighting elections. Even candidates from major political parties fighting state level elections spend more money than this. Candidates stay within these limits officially, but political parties spend much more money outside the set limits, during the course of campaigning.

What this tells us clearly is that political parties have got access to funding beyond what they have declared in the public domain. This money that comes to them is black money. This black money can possibly be the money that politicians have accumulated through corruption or money handed over by crony capitalists looking at possible favours in the days to come.

Hence, a crackdown on black money within the country would lead to the major source of funding for political parties and politicians being impacted. Guruswamy put it very aptly in his column when he said “Their own taps will run dry.”

Now, let me try and answer the first question, which was that why has the black money problem been allowed to become so huge? Why has it been left unattended for so many decades? As Daron Acemoglue and James A Robinson write in Why Nations Fail—The Origins of Power, Prosperity and Poverty “Political institutions determine economic institutions…Extractive political institutions concentrate power in the hands of a narrow elite and place few constraints on the exercise of power. Economic institutions are then often structured by this elite to extract resources from the rest of the society. Extractive institutions thus naturally accompany extractive political institutions. In fact, they must inherently depend on extractive political institutions for their survival.”

So what does this mean in the Indian context? It means that the Income Tax department, which is supposed to be unearthing the black money in this country, is corrupt because the politicians running this country are corrupt. The way the economic incentives of politicians have evolved has led to a situation wherein they simply cannot become active in cracking down on black money.

It explains why only 3.5 crore individuals out of a population of 120 crore pay income tax in this country.

To conclude, the question worth asking is, what will it take for politicians of this country get serious about unearthing black money?

The column originally appeared on www.equitymaster.com on Nov 14, 2014