Vijay Mallya is too much of a stiff upper lip to have ever read the Urdu poet Mirza Ghalib. But if he has, he would know, that one of Ghalib’s most famous couplets, fits the current situation that Mallya is in, very well.

Sometime in the nineteenth century Ghalib wrote:

Nikalna khuld se aadam ka soonte aaye hain lekin

Bahot be-aabru hokar tere kooche se hum nikle

(We have heard about the dismissal of Adam from Heaven,

With more humiliation, I left the street on which you live…

Source of translation: https://medium.com/@herahussain/poetry-in-the-east-a-journey-of-discovery-of-urdu-poetry-6197767f41b4)

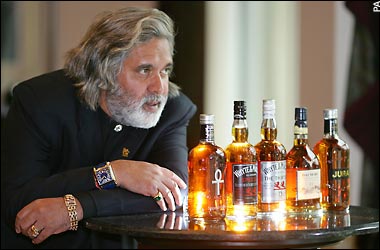

The board of United Spirits Ltd, India’s largest liquor company, has asked Mallya to step down as the Chairman of the company. The liquor baron may have been involved in financial irregularities as per an internal probe carried out by the company.

In a press release dated April 25, 2015, the company said: “The inquiry covered various matters, including certain doubtful receivables, advances and deposits. The inquiry revealed that between 2010 and 2013, funds involved in many of these transactions were diverted from the Company and/or its subsidiaries to certain UB Group companies, including in particular, Kingfisher Airlines Limited…The inquiry also suggests that the manner in which certain transactions were conducted, prima facie, indicates various improprieties and legal violations.”

Mallya in true Indian style has refused to bow out. ““All I wish to say is that I intend to continue as chairman of USL in the normal manner. This includes chairing monthly operating review meetings and board meetings,” he told the Mint newspaper.

Where does this confidence come from? Mallya personally holds 0.01% shares in United Spirits. United Breweries Holdings Ltd (controlled by Mallya) holds 2.90%. Other investment companies controlled by Mallya own around another 1.18%. So Mallya’s holding in United Spirits is down to a little over 4%.

Diageo, the British company to which Mallya sold United Spirits, owns 54.78% of United Spirits. Mallya’s confidence stems from the fact that while selling United Spirits, Mallya and Diageo entered into an agreement, as per which Diageo has to endorse Mallya as the Chairman of United Spirits. This, till Mallya has a stake in United Spirits.

Given this, the stage is set out for a messy legal battle, which will continue for sometime to come. Nevertheless, the question is how did Mallya end up in the mess that he has? One reason was that he took his flamboyant style a little too seriously and ended up starting Kingfisher Airlines in 2005.

Airlines are huge cash guzzlers. As Warren Buffett has said in the past: “The worst sort of business is one that grows rapidly, requires significant capital to engender the growth, and then earns little or no money. Think airlines. Here a durable competitive advantage has proven elusive ever since the days of the Wright Brothers. Indeed, if a farsighted capitalist had been present at Kitty Hawk, he would have done his successors a huge favor by shooting Orville down. The airline industry’s demand for capital ever since that first flight has been insatiable. Investors have poured money into a bottomless pit, attracted by growth when they should have been repelled by it.”

Kingfisher Airlines became Mallya’s bottomless pit. Mallya was in a rush to buy planes. He had plans of buying one Airbus A-320 every month until March 2012. All this needed a lot of money. Mallya loaded up on debt from public sector banks. At the same time, Mallya being Mallya could not have run a low cost airline. In a October 2012 article, Tehalka quotes an aviation sector CEO as saying: “Food served in KFA[Kingfisher Airlines], recalls an aviation sector CEO, was about Rs 700-800 per passenger compared to Rs 300 of Jet’s.”

Other than this Mallya was in a hurry to fly Kingfisher to international destinations. A domestic airline was allowed to do that only once it had completed five years of operation. That meant that Kingfisher would be allowed to fly abroad only by 2010. Mallya did not have the patience to wait for that long. He bought Air Deccan in 2007 to get around the regulation. He ended up overpaying for the low cost airline.

Further, he rebranded Air Deccan as Kingfisher Red. By doing this he diluted the premier positioning that Kingfisher Airlines had acquired in the minds of the consumer. The philosophy required to run a premium brand is totally different in comparison to the philosophy required to run a low cost brand. Hence, Mallya buying Air Deccan was mistake. And then changing its name to Kingfisher Red was an even bigger mistake.

So in the end this did not work and Mallya decided to close down Kingfisher Red. He explained it by saying that “We are doing away with Kingfisher Red, we do not want to compete in the low-cost segment. We cannot continue to fly and make losses, but we have to be judicious to give choice to our customers.”

It is very difficult to run a full-service airline as well as a low cost airline at the same time. The basic philosophy required in running these two kind of careers is completely different from one another. The full service Kingfisher also soon ran into trouble leaving Mallya with a lot of debt. He had got terrible publicity for not paying the salaries of employees of Kingfisher Airlines.

Other than running the liquor and the airline business, Mallya also has interests in real estate. Over and above this, he also indulged in expensive hobbies by buying a formula one and an IPL cricket team. Running an airline is a full time business and can’t be done in a part-time sort of way which Mallya did.

The best Indian companies in the last few decades have made money by concentrating on one line of business. Airtel made money in telecom. It did not make money trying to sell us insurance and mutual funds. The same stands true about DLF. Tata, Birla and Ambani, all lost money in the retail business. Businesses over the years have become more complicated. And just because a promoter has been good at one particular business doesn’t mean it will be good at another totally unrelated business. Mallya did the same with his main liquor business, which he is now losing control of.

Over the last few years, Mallya has been battling the banks which have been going after his assets, for all the debt that is unpaid. To conclude, Mallya has always been too busy living his flamboyant lifestyle and that seems to have caught up with his businesses in the end.

(Vivek Kaul is the author of the Easy Money trilogy. He tweets @kaul_vivek)

The column originally appeared on www.Firstpost.com on Apr 27, 2015