One of the favourite arguments offered by middle class Indian men (especially when all other arguments fail) is that “India needs a benevolent autocrat,” if the economy has to grow at a fast pace. The word “autocrat” is often used interchangeably with the world “dictator”.

This argument is often made by the corporate types who have made their money in life and are now looking for some intellectual stimulation through what they consider as philosophical musings.

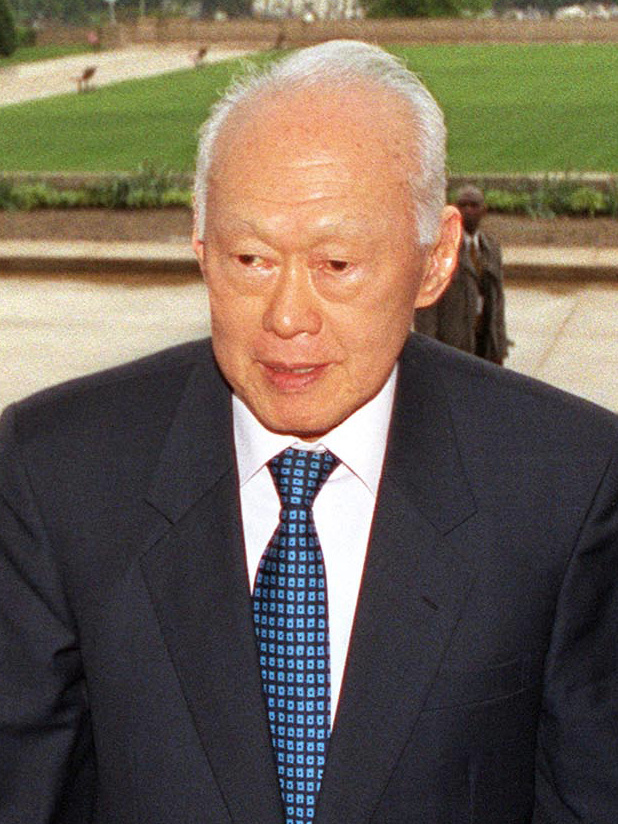

The argument has gained a new life with the death of Lee Kuan Yew (or LKY as he was commonly known as) who was the prime minister of the city-state of Singapore from 1959 to 1990. Between 1990 and 2011, he was the senior minister as well as minister mentor of Singapore. LKY died on March 23, 2015.

Data from the World Bank shows that the per capita income of Singapore in 2013 was $55,182.5. When LKY took over as the prime minister in 1959, the per capita income was $400. What this clearly tells us is that LKY turned around Singapore from a poor country to a developed country in about one generation. When he became the prime minister, Singapore was basically swamp with almost no natural resources. He turned it around into a global financial centre first and now an entertainment destination as well.

His achievements not withstanding, LKY was an autocrat who was honest enough to admit it. As he said in an interview to The Straits Times in April 1987: “I am often accused of interfering in the private lives of citizens. Yes, if I did not, had I not done that, we wouldn’t be here today. And I say without the slightest remorse, that we wouldn’t be here, we would not have made economic progress, if we had not intervened on very personal matters – who your neighbor is, how you live, the noise you make, how you spit, or what language you use. We decide what is right. Never mind what the people think.”

But as I have said above LKY’s autocratic style of working paid huge dividends for Singapore. It was transformed from a swamp to a developed country in around 50 years. And that was a huge achievement.

This high growth that Singapore achieved has led people to suggest that India also needs a benevolent autocrat to grow at a fast pace. LKY and Singapore are not the only example that is given to buttress this point. There are other examples as well—Chile under Augusto Pinochet. Or countries like Hong Kong, Singapore, South Korea and Taiwan, which grew at a very fast rate under autocratic regimes. They moved to a democratic form of government only after having grown fast for a significant period of time.

Then there is the example of China. The country is ruled by one party, the Chinese Communist Party (CCP). It has had a generation of fast economic growth without any democracy. All this has led many people to believe that if a country has to grow fast it needs to be under an autocratic regime. Hence, India needs a “benevolent autocrat,” is the argument offered. QED.

But are things as simple as that? Or are people becoming victims of what behavioural economists term as the “availability heuristic”? As John Allen Paulos writes in A Mathematician Reads the Newspaper: “First described by psychologists Amos Tversky and Daniel Kahneman, it is nothing more than strong disposition to make judgements or evaluations in light of the first thing that comes to mind (or is “available” to the mind).”

So, Lee Kuan Yew was an autocrat. Under him Singapore grew at a very rapid rate. Hence, India needs a benevolent autocrat as well, if it has to grow at a very fast rate. That’s how it works for those who feel that India needs a “benevolent autocrat”.

Economist William Easterly has done some interesting research in this area, which he summarises in a research paper titled Benevolent Autocrats. As he writes: “The probability that you are an autocrat IF you are a growth success is 90 percent. This probability seems to influence the discussion in favour of autocrats.”

But that is the wrong question to ask. The question that needs to be asked should be exactly opposite—if a country is governed by an autocrat what are the chances that it will be a growth success? “The relevant probability is whether you are a growth success IF you are an autocrat, which is only 10 percent,” writes Easterly. To put it simply—most fast growing nations are ruled by autocrats. Nevertheless, most autocracies do not grow fast.

The thing is that one never knows whether an autocrat will turn out to be benevolent or will he turn out to be an out an out dictator, once he starts to rule. That depends on the luck of the draw. Most autocrats usually end up screwing up the economies they rule. This is a simple point that middle class Indian men who want a “benevolent autocrat” to rule this country, need to understand.

(Vivek Kaul is the author of the Easy Money trilogy. He tweets @kaul_vivek)

The column originally appeared on Firstpost on Mar 30, 2015