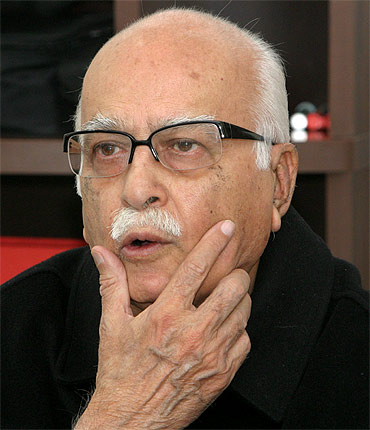

Lal Krishna Advani in his dreams must sometimes wish that he should have belonged to the Nehru-Gandhi family. Irrespective of what happens to the political fortunes of the Congress, the Nehru-Gandhis remain at the top.

Even when the party is not under the control of a Nehru-Gandhi, the Congress politicians keep conspiring endlessly till they have managed to install a Nehru-Gandhi at the helm of affairs. This was clearly the case between 1991-1996, after Rajiv Gandhi was assassinated and his widow Sonia refused to take over. Nevertheless the Congress installed Sonia as the president of the party as soon as she was ready.

As Rasheed Kidwai writes in Sonia – A Biography “Throughout the Narsimha Rao regime, 10 Janpath[where Sonia continues to stay] served as an alternative power centre or listening post against him.” In December 1997, Sonia Gandhi indicated that she wanted to play a more active role in Congress politics. It took the party less than three months to throw out Sitaram Kesri, the then President of the party and put Sonia in charge in his place.

Advani has not been anywhere as lucky as Sonia. In fact, he has constantly been sidelined in the Bhartiya Janata Party (BJP) over the last five years. And unlike Sonia, who continues to enjoy the spoils of the hard-work of her husband’s ancestors, Advani built the BJP right from scratch.

The final nail in the coffin for Advani was the decision by the newly appointed BJP president Amit Shah to drop him from the 12-member Parliamentary Board of the Party. Advani though has been included in the newly created margadarshak mandal, where he is unlikely to have any decision-making powers.

In fact, Advani had to recently go through the ignominy of his nameplate being removed from his room in Parliament (the nameplate was put back later). This after being denied the post of the Lok Sabha Speaker, which he wanted. All this must be too much to handle for a man who is BJP’s senior most active leader, and refuses to retire.

The BJP was formed on April 5-6, 1980, after it broke away from the Janata Party. The Janata Party had been formed a few years earlier in 1977, with the merger of Congress O, Bhartiya Lok Dal, the Socialist Party and the Jana Sangh (the BJP’s earlier avatar), with the idea of taking on Indira Gandhi and her Congress party in the 1977 Lok Sabha elections.

The Janata Party won 295 seats in the elections, with 93 MPs coming from the erstwhile Jana Sangh. But trouble soon broke out and different constituents of the party could not get along with each other. This experiment against the Congress ended in 1980, and the BJP was formed. Atal Bihari Vajpayee became the president of the BJP, and Advani was its general secretary.

Interestingly, the party chose “Gandhian socialism” as its credo. Kingshuk Nag writes in The Saffron Tide—The Rise of the BJP that a “consensus emerged…on Gandhian socialism being the credo of the new party; in other words, it would fashion itself like the Janata Party.”

Advani explains this in his autobiography My Country, My Life: “The stress from the beginning was not on harking back to our Jana Sangh past but on making a new beginning.” The new beginning happened primarily because both Vajpayee and Advani had been influenced a lot by Jaiprakash Narayan, who was the main architect behind the Janata Party.

Also, what did not help was the fact that Indira Gandhi in her second avatar as the Prime Minister had in a way hijacked the “Hindutva” agenda, which the Jan Sangha had stood for. “Indira Gandhi had become religious with vengeance after coming to power in 1980 and began visiting temples with fervour. In public imagination, the impression created was that of a Hindu lady seeking the benefaction of the Gods. The policies in her tenure were also interpreted as being pro Hindu,” writes Nag.

This newly discovered “Gandhian socialism” did not work for the BJP in the Lok Sabha elections that happened in December 1984, after the assassination of Indira Gandhi by her bodyguard. The party won just two seats in this election. A committee was formed to try and understand the reasons for the electoral debacle.

As Nag writes “The committee…found a lot of lacunae in the working of the BJP. The committee also commented on the lack of political training of workers on political, economic, idealogical and organizational matters.” Or as a BJP insider told Nag “Basically, the committee politely said the party was going nowhere.”

Vajpayee resigned in the aftermath of the debacle and Advani took over as the president of the party. With Advani at the helm, the relations with the Rashtriya Swayemsevak Sangh(RSS) also improved significantly. In the years to come, the BJP went back to Hindutva and gradually junked “Gandhian Socialism” as its main credo. In fact, in 1990, Advani launched a rath yatra in which he wanted to travel in a motorized van from Somanth in Gujarat to Ayodhya in Uttar Pradesh.

But before he could enter Uttar Pradesh, Lalu Prasad Yadav got Advani arrested in Bihar. As Advani recounts in his autobiography “My yatra was scheduled to enter Deoria in Uttar Pradesh on 24 October. However, as I had anticipated, it was stopped at Samastipur in Bihar on 23 October and I was arrested by the Janata Dal government in the state then headed by Laloo Prasad Yadav (sic). I was taken to an inspection bungalow of the irrigation department at a place called Massanjore near Dumka on the Bihar-Bengal border [Dumka now comes under the state of Jharkhand].”

Even though Advani could not complete the yatra it was a huge success and Advani was greeted by huge crowds wherever he went. “At some places, charged-up followers applied tilak to the Ram rath while at other places, those moved by the movement smeared dust from the path of the rath on their forehead,” writes Nag.

Advani went around building the party on the ideology of hardcore Hindutva, taking the number of seats that the party had in the Lok Sabha to 85 in 1989 and 120 in the 1991. This fast rise of the party was built on slogans like “saugandh Ram ki khaate hain mandir wohin (i.e. Ayodhya) banayenge” and “ye to kewal jhanki hai Kashi Mathura baaki hai”. As Advani went about his job, Vajpayee took a back-seat for a while.

Nevertheless, Advani soon realized that temple and Hindutva politics could only get the party to a certain level. He also realized that he was looked at as a Hindu hardliner and as long as he led the party, it would never be in a position to form the government. Hence, in November 1995, at the end of his presidential address at the BJP national council meet held in Mumbai, he announced that “We will fight the next elections under the leadership of A.B.Vajpayee and he will be our candiate for a prime minister…For many years, not only our party leaders but also the common people have been chanting the slogan, “Agli baari, Atal Bihari”.”

This was a political master stroke. At the same time it needs to be said that not many people would have been able to make the decision that Advani did, if they had been in his position. It is never easy to build an organisation right from scratch and then hand it over to someone else, to lead it.

With Vajpayee at the helm, other poltical parties were ready to ally with the BJP. The BJP led National Democratic Alliance first came to power in 1998. They were in power till 2004, when they lost the Lok Sabha elections. After the 2004 Lok Sabha elections, Vajpayee gradually faded from the limelight.

In these years, the spin-doctors of Advani had managed to tone down his image as a Hindu hardliner. This can be very gauged from the fact that Nitish Kumar had no problem with being in alliance with an Advani led BJP, but he wasn’t ready to work with a Narendra Modi led BJP.

The NDA fought the 2009 Lok Sabha elections under the leadership of Advani and lost. And from then on, the stock of Advani has constantly fallen in the BJP. The decision to drop him from the Parliamentary Board of the party, as mentioned earlier, is probably the last nail in the coffin of his political career.

Interestingly, Narendra Modi was also handpicked by Advani to play a greater role in the BJP. As Nilanjan Mukhopadhyay writes in Narendra Modi – The Man. The Times “From the beginning it was evident that Modi was Advani’s personal choice and he was keen to strengthen the unit in Gujarat because the state was identified as a potential citadel in the future.”

Advani also mentored Modi during his early days in politics. “It was Advani who mentored Modi when he virtually handpicked him into his team of state apparatchiks after recommendations from a few trusted peers in the late 1980s. Advani also gave Modi early lessons in how to convert the mosque-temple dispute into one of national identity,” writes Mukhopadhyay.

But in the recent years while Advani’s stock within the BJP and the RSS has fallen dramatically, Modi’s stock has been on a bull run. The shishya has become the guru. The trouble is that the guru does not want to retire, and is probably still itching for a one-last-fight.

But there is not much that he can do about it. Advani’s side-lining is an excellent lesson of what happens when one overstays one’s welcome in politics as well as life. There is a time to work. And there is time to retire and move on.

To conclude, Advani’s one remaining political ambition would have been to become the prime minister of India. But that somehow did not happen. As Salamn Rushdie aptly put in Midnight’s Children “This is not what I had planned; but perhaps the story you finish is never the one you begin.”

The article originally appeared on www.firstpost.com on August 29, 2014

(Vivek Kaul is the author of the Easy Money trilogy. He tweets @kaul_vivek)