Vivek Kaul

“Ek bandra station,” I told the conductor of the B.E.S.T (BrihanMumbai Electric Supply and Transport) bus number 83, handing over a ten rupee note.

“Do rupiya aur,” he replied.

“12 rupiya ka ticket hai?” I asked him.

“Ji sir,” he replied.

I was travelling from Century Bazar in Worli to Bandra. The ticket till very recently used to cost eight rupees. It has now been increased to Rs 12, a rather steep 50% increase. The prices of tickets of lower denominations haven’t been increased so much. A four rupee ticket is now five rupees. But at the same time a ten rupee ticket now costs fifteen rupees and a twelve rupee ticket costs eighteen rupees.

This got me thinking. Why had the B.E.S.T increased prices? Well for the simple reason that they had to match their income with their expenditure, which is the most basic thing that needs to be done for successfully operating any institution. The fact that it is not allowed to raise prices as often as it probably wants to has led to this very high increase.

While the B.E.S.T believes in at least trying to ensure that its income meets its expenditure, the United Progressive AllianceUPA) which runs the government of India, doesn’t. And this is neither good for the UPA nor for you and me, the citizens of India.

In the year 2007-2008 (i.e. between April 1, 2007 and March 31,2008) the fiscal deficit of the government of India stood at Rs 1,26,912 crore. Fiscal deficit is the difference between what the government earns and what it spends. For the year 2011-2012 (i.e. between April 1, 2011 and March 31, 2012) the fiscal deficit is expected to be Rs 5,21,980 crore.

Hence the fiscal deficit has increased by a whopping 312% between 2007 and 2012. During the same period the income earned by the government has gone up by only 36% to Rs 7,96,740 crore.

Things cannot be quite right when your expenditure is expanding nine times as fast as your income. As Franklin Roosevelt, who was the President of America for a record four times, between 1933 and 1945 famously said “Any government, like any family, can, for a year, spend a little more than it earns. But you know and I know that a continuation of that habit means the poorhouse.”

So why is the UPA led Indian government headed to the poorhouse? For that we have to dig a little deep and look into this document known as the annual financial statement of the government of India. In this document the government gives out numbers for the amount it had assumed initially as the oil subsidy for the year, and the final oil subsidy it gave.

The data for the last three years has been very interesting. The subsidy assumed at the time of the finance minister presenting the budget has always been much lower than the final subsidy bill. Take the case for the year 2009-2010(i.e. between April 1, 2009 and March 31,2010) the oil subsidy assumed was Rs 3109 crore. The final bill came to Rs 25,257 crore (direct subsidies + oil bonds issued to the oil companies), around eight times more.

The next year (i.e. between April 1, 2010 and March 31, 2011) the oil subsidy assumed was Rs 3108 crore. The actual bill was nearly 20 times more at Rs 62,301 crore. For the year 2011-2012(i.e. between April 1,2011 and March 31,2012) the subsidy assumed was Rs 23,640 crore. The actual subsidy bill came to Rs 68,481 crore.

So in each of the last three years the oil subsidy bill has come out to be greater than what was assumed. For the current financial year (i.e. April 1, 2012 to March 31,2013) the oil subsidy bill has been assumed to be at Rs 43,580 crore. While this is greater than the assumption made over the last three years, it is highly likely that the oil subsidy bill will come to amount greater than this.

There are two reasons for the same. The first reason is that the rupee has been rapidly depreciating against the dollar and since oil is sold in dollars that means that the Indian companies are paying up more in rupees to buy the same volume of oil. Currently oil is priced at around $115 per barrel (around 159litres) of oil. This means that Indian companies pay around Rs 6141 per barrel of oil.

If the rupee falls further and one dollar equals Rs 60 (as has been written about on this website), the Indian companies will be paying Rs 6900 or 12.4% more per barrel of oil. In the normal scheme of things this cost would have been passed onto the customer and everybody would have lived happily ever after.

But that is not the case. Various products coming out of oil like kerosene, diesel etc, are heavily subsidized in India. Hence even with higher prices of oil internationally the Indian oil companies will have to keep selling their products at lower prices and suffer losses. These companies are then compensated for the losses they face by the government of India.

The second reason is that the price of oil is unlikely to go down in dollar terms as well. As governments and central banks around the world run close to zero interest rates and print more and more money (and are likely to continue to do so) in order to revive economic growth in their respective countries, oil has become a favourite commodity to buy among the speculators.

While central banks and governments can print all the money they want, they can’t dictate where it goes. As Ruchir Sharma writes in Breakout Nations – In Pursuit of the Next Economic Miracles “When money is loose, investors borrow to buy hard assets, which is why the prices of oil, copper, and other commodities have become disconnected from actual demand.”

This means that oil will either continue at its current price level or even go up for that matter. And with the rupee likely to depreciate further this means that India’s oil import bill is likely go up even further.

It is highly unlikely that this increase in price will be passed onto the end customer. This means that the government will have to bear the losses incurred by the oil companies, pushing up the oil subsidy, which has been assumed to be at Rs 43,580 crore.

A higher oil subsidy bill means the government expenditure going up and this in turn means a higher fiscal deficit. Typically, the government finances this deficit by borrowing money. With the government needing to borrow more money it would have to offer a higher rate of interest. At the same time a higher government borrowing will crowd out private borrowing, meaning that the private borrowers like banks and other finance companies will have to offer a higher rate of interest on their deposits because there would be lesser amount of money to borrow. A higher rate of interest on deposits would obviously mean charging a higher rate of interest on loans.

All this can be avoided if the government follows what B.E.S.T did recently i.e. allow oil companies to raise prices of its products. Why can’t a free market operate when it comes to oil products? If the price of oil products changes on a daily basis depending on its international price, like the price of vegetables, people will gradually get used to the idea of a changing price for products like diesel and kerosene.

And of course chances are that with the government borrowing coming down, interest rates might also fall. In 2007, when the government fiscal deficit was low, a 20 year home loan could be got at an interest rate of 8%. A loan of Rs 25 lakh would mean an EMI(equated monthly installment) of around Rs 25,093. A lot of banks are now charging their existing consumers around 13% on their home loans. This means an EMI of around Rs 35,147 or almost 40% more.

The huge subsidy on oil prices has had a role to play in this increasing EMI. Bad economics does not always mean good politics. Its time UPA woke up to that.

(The article was originally published on May 9, 2012,at http://www.rediff.com/business/slide-show/slide-show-1-special-what-the-upa-govt-can-learn-from-best/20120509.htm. Vivek Kaul is a writer and can be reached at [email protected])

Gold is about to touch Rs 30,000. What to do now?

The price of gold has been rising and might touch Rs 30,000 per ten grams very soon(it is currently around Rs 29,300 per 10 grams). If you had invested Rs 1 lakh in gold five years back, it would currently be worth around Rs 3.1lakh. In comparison Rs 1 lakh invested in the stocks that constitute the BSE Sensex would now be worth Rs 1.22 lakh.

So clearly gold has done much better than Indian stocks have. But will it continue to give the kind of returns that it has in the past? Before I try and answer that question, let’s get into a little bit of history and try and understand why people buy gold.

Queen Elizabeth I who ruled England in the sixteenth century used to have a financial advisor by the name of Sir Thomas Gresham. Gresham had been appointed to clear up the financial mess created by the Queen’s father Henry VIII and her brother Edward VI, who had ruled before her.

Between them they had completely destroyed the pound by debasing it and ensuring that there was very little silver left in it. Kings and governments throughout history have had a habit of debasing coins and other forms of money. Nero, King of Rome, and who watched it burning, was one of the first Kings to debase coin.

Debasement was a practice where the ruler or the government of the day decided to lower the metal content of the coin while keeping its value unchanged. Let us try and understand this through the example of a coin which has a face value of 100 cents (or any other unit for that matter). The face value of a coin is referred to as its tale. This coin is made up of a metal (gold or silver) and the metal content of the coin is worth 100 cents as well. The metal content in a coin is referred to as specie.

So in this example the tale of the coin is equal to its specie, which is the ideal situation. Now the ruler decides to debase the coin by 20%. So he reduces the metal content or the specie value of the coin by 20% to 80 cents. But at the same time he maintains the face value of the coin at 100 cents. And thus debases the coin.

In most situations the rulers used to pocket the metal (gold or silver) they had saved by debasing the coin. The situation in Britain at the start of Elizabeth’s rule was similar and the market that was full of debased coins.

She wanted to correct the situation and decided to launch new silver coins where the tale of the coin was equal to its specie i.e. the face value of the coin was equal to the amount of metal in it.

But her financial advisor Gresham thought that there would be a major problem in doing that. He felt that the bad money would drive out the good. This essentially meant that the citizens of the country would hold onto the full metal new coins and try and carry out their transactions through the existing debased coins.

They would melt the newer coins for the greater amount of silver in them and sell them for their precious metal content. Hence bad money would drive out the good. This phenomenon came to be known as the Gresham’s law. Gresham decided to solve problem by exchanging all the old coins for new coins. This would ensure that there would be no old coins in the market and people would move onto using the new coins as money.

Even though Gresham’s name came to be attached to this phenomenon, this had been happening for thousands of years. “,“Under the Greeks and Romans, when gold coins were debased, few people were dumb enough to want to exchange their old coins that had high gold content for newer ones that had low gold content, so older good coins disappeared as people hid them,” writes hedge fund manager John Mauldin.

In fact it is even being observed today, though in a different form. Central banks and governments around the world have been printing money in the hope of tiding over the financial crisis and reviving economic growth in their respective countries.

When the governments print money there is much more money in the financial system than before, and hence the money gets debased. To protect themselves against this debasement people buy gold, something that cannot be created out of thin air and thus is expected to hold value.

So as governments have been printing money, people have been buying gold and the price of gold has been going up. Till early 1930s, paper money around the world used to be backed by gold or silver. This meant that citizens at any point of time could go to the central bank of the governments and its various mints and exchange their paper money for gold or silver.

Hence whenever people saw that the government was resorting to money printing, they could get their money converted into gold or silver, and thus ensure it did not lose its value. Now the paper money is not backed by anything except a fiat from the government which deems it to be money.

Given this, now whenever people see more and more of paper money, the smarter ones simply go out there and buy that gold. Hence, as was the case earlier, bad money (that is, paper money), drives out good money (that is, gold) away from the market.

But that’s just one part of the story. The governments around the world are likely to continue printing more money, in the hope that people spend this money and this revives economic growth. This in turn would mean that the price of gold is likely to go up in dollar terms. It is important to remember that gold is bought and sold worldwide in dollar terms and not in terms of Indian rupees. Hence whether Indians will continue to benefit from the price of gold continuing to go up will depend on a few other factors.

Let us examine four possible scenarios:

1) The price of gold goes up in dollar terms and the rupee continues to depreciate against the dollar: This is what has happened over the last one year. In dollar terms gold has given a return of 6.1% over the last one year. But in rupee terms the return is almost four and a half times more at 27.3%. Why is this the case? A year back one dollar was worth Rs 44. Now it’s worth almost Rs 54. So the gold price has increased in dollar terms but because of the depreciation of the rupee, the returns of gold in rupee terms are a lot higher. If gold quotes at $1600 per ounce (around 31.1grams), and one dollar is worth Rs 44, then the price of gold in rupee terms is Rs 70,400(1600 x 44) per ounce. If one dollar is worth Rs 54, the price of gold increases to Rs 86,400 per ounce. So the depreciation of the rupee against the dollar can spruce up returns for the Indian gold investor. Even if gold prices remain flat, and the Indian rupee keeps depreciating against the dollar, there is money to be made in gold. But the ideal situation for an Indian gold investor is that the price of gold goes up in dollars and at the same time the rupee depreciates against the dollar.

2) The price of gold in dollar terms falls and the rupee depreciates against the dollar, so as to knock off the fall in price in dollar terms: This is a phenomenon that has been observed over the last six months. The price of gold in dollar terms had gone down by around 7.4%, whereas in rupee terms the return on gold has been around 1%. This is because six months back one dollar was worth around Rs 51, now it’s worth Rs 54. So even though the price of gold has fallen in dollar terms, a depreciating rupee has more than made up for it.

3) The price of gold in dollar terms falls and the rupee appreciates against the dollar: This is a scenario that the Indian gold investor does not want. An appreciating rupee will further accentuate the negative returns of gold. This is a scenario that is highly unlikely. The chances of gold price falling majorly remain low as there is no end in sight to the financial crisis. Also with the government of India being in the mess it is, the chances of rupee appreciating also remain very low.

So the moral of the story is that even if the price of gold goes up in dollar terms, for Indian gold investors to continue to make money, the rupee has to either depreciate against the dollar or to at least remain flat. The rupee is likely to continue to lose value against the dollar and thus there are still more gains to be made on gold. But these gains will be rather limited till gold does not rally majorly against the dollar, which it hasn’t for the last one year.

The moral of the story is that stay invested in gold. But don’t bet your life on it.

(The article originally appeared on http://www.firstpost.com/investing/gold-is-about-to-touch-rs-30000-what-to-do-now-299622.html on May 7,2012. Vivek Kaul is a writer. He can be reached at [email protected])

‘US, India are now on the verge of a social revolution’

Ravi Batra is an Indian American economist and a professor at the Southern Methodist University in Dallas, Texas. Unlike most economists who are in the habit of beating around the bush, Batra likes to make predictions, and he usually gets them right. Among these was calling the fall of communism in the Soviet Union more than ten years before it happened. Batra is also the author of many best-selling books like The Crash of the Millennium, The Downfall of Capitalism and Communism, Greenspan’s Fraud and most recently The New Golden Age. In this interview he speaks to Vivek Kaul.

Excerpts:

You are a great proponent of the Law of Social Cycle. What’s it all about?

In 1978, to the laughter of many and the ridicule of a few, I wrote a book called The Downfall of Capitalism and Communism, which predicted the demise of Soviet communism by the end of the century and an enormous rise in wealth concentration in the United States that would generate poverty among its masses, forcing them into a revolt around 2010. My forecasts are derived from The Law Of Social Cycle, which was pioneered by my late teacher and mentor Prabhata Ranjan Sarkar. Lo and behold! The Berlin Wall fell in 1989 and Soviet communism vanished right before your eyes. And in 2011, the United States witnessed the birth of a social revolt in the form of the ‘Occupy Wall Street Movement’, which opposes the interest of the richest 1% of Americans. The nation now has the worst wealth concentration in history.

So what is this law?

It is an idea that begins with general characteristics of the human mind. Sarkar argues that while most people have common goals and ambitions, their method of achieving them varies, depending on innate qualities of the individual. Most of us, for instance, seek living comforts and social prestige. Some try to attain them by developing physical skills, some by developing intellectual skills and some by saving and accumulating money, while there are also some with little ambition in life. Based on these different mentalities, Sarkar divides society into four distinct classes: warriors, intellectuals, acquisitors and labourers.

Can you go into a little more detail?

Among warriors are included the military, policemen, professional athletes, fire fighters, skilled blue-collar workers, and anyone who displays great courage. The class of intellectuals comprises teachers, scholars, bureaucrats, and priests. Acquisitors include landlords, businessmen, merchants, and bankers. Finally, unskilled workers constitute the class of laborers. The division of society into four classes based on their mentality and occupations, not heredity, is at the core of Sarkar’s philosophy of social evolution. His theory is that each society is first dominated by the class of warriors, then by the class of intellectuals, and finally by the class of acquisitors. Eventually, the acquisitors generate so much greed and materialism that other classes, fed up by the acquisitive malaise, overthrow their leaders in a social revolution. Then the warriors make a comeback, followed once again by intellectuals, acquisitors and a social revolution. This, in brief, is The Law Of Social Cycle.

That’s very interesting. Can you explain this through an example?

Applying this theory to western society, we find that the Roman Empire was the Age Of Warriors, the rule of the Catholic Church the Age Of Intellectuals, and feudalism the Age Of Acquisitors, which ended in a social revolution spearheaded by peasant revolts all over Europe in the 15th century. The centralised monarchies that then appeared represented the Second Age Of Warriors, which was, in turn, followed by another Age Of Intellectuals, this time represented by the rule of prime ministers, chancellors and diplomats. Since the 1860s the west has had a parliamentary rule in which money or the acquisitive era has been prevalent.

What about India?

India’s history is silent on some periods, but, wherever full information is available, the social cycle clearly holds. For instance, around the times of Mahabharata, warriors dominated society, then came the rule of Brahmins or intellectuals, followed by the Buddhist period, when capitalism and wealth were predominant; this era ended in the flames of a social revolution, when a great warrior named Chandragupta Maurya put an end to the reign of a king named Dhananand, and started another Age Of Warriors. Dhan means money and ananda means joy, so that dhan + ananda becomes Dhananda or someone who finds great joy in accumulating money, suggesting that the Mauryan hero overthrew the rule of greed and money in society.

How do you see things currently through The Law Of The Social Cycle?

Today, the world as a whole is in the Age Of Acquisitors, while some nations such as Iran are ruled by the clergy or their intellectuals. Russia is in transition from the warrior era to the era of intellectuals, while China continues in the Age Of Warriors, which was founded by Mao Tse Tung in 1949 after overthrowing the feudalistic Age Of Acquisitors in an armed revolution. As regards Iran, applying the dictum of social cycle, I foresaw the rise of priests or the Ayatollahs in a 1979 book called Muslim Civilization and the Crisis in Iran. For ten thousand years, the law of the social cycle has prevailed. Egypt went through three such cycles before succumbing to Muslim power. Muslim society as a whole is now in the Age Of Acquisitors. Some Muslim countries such as Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, Jordan, Pakistan, Malaysia and Bahrain are still in the acquisitive age, while some others such as Egypt and Libya have recently seen a social revolution and are in transition to the next age. The wheel of social cycles has thus been turning in all societies, albeit at different speeds; not once in human history was it thwarted.

Any new predictions based on this law?

The United States along with India are now on the verge of a social revolution that will culminate in a Golden Age. That is what I have predicted in my latest book, The New Golden Age. The American revolution is likely to occur by 2016 or 2017, and India’s should arrive by the end of the decade. This is the way I look at some popular movements such as the Occupy Wall Street Movement in the United States, and those started by Anna Hazare and Baba Ram Dev in India. They reflect people’s anger and frustration with the corrupt rule of acquisitors. Such movements are destined to succeed in their mission, because the rule of wealth is about to come to an end.

One of your predictions that hasn’t come true is that about the Great Depression of the 1930s happening again

It is true we have not had another Great Depression like that of the 1930s, although the slump since 2007 is now being called the Great Recession. The difference between the two may be more semantic than real. The Great Depression was not a period of one long slump lasting for the entire 1930s. Rather, there were pockets of temporary prosperity. The first part of the depression lasted between 1929 and 1933. Then growth resumed and the global economy improved till1937, only to be followed by another slump. This time there has been no depression, but at least in the United States people’s agony has been nearly as bad as in the 1930s. Farming played a great role in society at that time so that the unemployed could go back to agriculture and survive. This time around, that has not been possible. Millions of Americans are homeless today as in the1930s. Still the 1930s were the worst ever, but my point is that American poverty today is the worst in fifty years. The wage-productivity gap, consumer debt and the stock market went up sharply in the 1920s, just as they did after1982. The market crashed in 1929 and then the depression followed. So I concluded that since the same type of conditions were occurring in the 1980s we would have another great depression. However, what I could not imagine was that, China, one-time America’s arch enemy, would lend trillions of dollars to the United States. Note that so long as debt keeps up with the rising wage gap, unemployment can be avoided. In other words, China’s loans postponed large-scale unemployment in the United States for a long time, but not forever.

Can a depression still occur?

Yes, it can, but only if countries are unable to create new debt. Such a likelihood is small but cannot be ruled out. On the other hand, if for some reason oil prices shoot up further to say $150 per barrel, the depression will be inevitable.

How do you see the scenario in Europe playing out?

In Europe and elsewhere the nature of the problem is the same, namely the rising wage gap, so that production exceeds consumer demand, and the government has to resort to nearly limitless debt creation. But the PIIGS — Portugal,Ireland, Italy, Greece and Spain — show that government debt cannot rise forever and when debt has to be reduced there is further rise in unemployment. The European troubles are not over and we should expect the debt problem to linger for years to come.

The dangers in Europe have suddenly taken away the attention from the United States. What is your prediction about the United States the way it currently is?

So long as the United States is able to borrow more money either from the world or from its own people, its economy will remain stable at the bottom. But there is a strong sentiment now among most Americans that the budget deficit must come down, and the laws already passed aim to bring it down from 2013 on. This is likely to raise unemployment in that year and beyond. 2012 could also see real troubles after June when the already rising price of oil and gasoline starts hurting the economy. If the speculators succeed in raising the oil price towards their goal of $150, there could be another serious slump by the end of the year.

Do you see a dollar crash coming in the years to come?

Yes the dollar could crash against the currencies of China and Japan, but I don’t see this happening before July. After that the global economy could be as sick as it was in 2008. The scenario would be reminiscent of what happened in 1937 when the global depression made a comeback. Something similar could materialise again in that the Great Recession could make a resounding come back. However, I don’t see an alternative to the dollar at this point because the whole world is in trouble. For the dollar to fall completely from grace, Opec would have to start pricing its crude in terms of a different currency and I am not sure if that is possible.

What do you think about the current steps the Obama administration is taking to address the economy?

The Obama administration has followed almost the same policies that George W Bush did, and in the process wasted a lot of money to generate paltry economic growth and some jobs. In fact, the government has been spending over $1.5 million to generate one job. This sounds bizarre, but here is what has happened since 2009. The administration’s tack is that we should keep spending money at the current rate to lower unemployment, even though the annual federal budget deficit has been around $1.4 trillion over the past two years. It seems apparent that the main purpose of excessive federal spending is to preserve or generate jobs. This is a point emphasised by every American president since 1976, and especially since1981 when the federal deficit began to soar. This is also how most experts defend the deficit nowadays.

Could you elaborate a little more on this?

In 2010, according to the Economic Report of the President, as many as 800,000 jobs were created, and the government’s excess spending was $1.4trillion, which when divided by 800,000 yields 1.7 million. In other words, the US government spent $1.7 million to generate one job. The economy improved in 2011, providing work to 1.1 million people for the same expense. So dividing $1.4 trillion by the new figure yields $1.3 million, which is now the cost of creating one job. Thus, the average federal deficit or cost per job over the past two years has been $1.5 million.

Is it prudent to be wasting precious resources like this?

I don’t think so. The trillion dollar question is this: where is it all going, when the annual American average wage is no higher than $50,000? Obviously, it must be going to the so-called 1% group or what the Republican Party calls the job creators, i.e., the CEOs and other executives of large corporations.

Could you explain that?

Let us see how the main culprit for the mushrooming incomes of business magnates is the government itself. This is how the process works and has been working since 1981. The CEO forces his employees to work very hard while paying them low wages; this hard work sharply raises production or supply of goods and services, but with stagnant wages, consumer demand falls short of growing supply. This then leads to overproduction and threatens layoffs, which in turn threatens the re-election chances of politicians. They then respond with a massive rise in government spending or huge tax cuts, so that total demand for goods and services rises to the level of increased supply. As a result, either those layoffs are averted or the unemployed are gradually called back to work. This way, the CEO is able to sell his entire output and reap giant profits in the process, because wages are dwindling or stagnant even as business revenue soars. In the absence of excess government spending, companies would be stuck with unsold goods and could even suffer losses. In other words, almost the entire federal deficit ends up in the pockets of business executives. With such a vast wastage of resources, the economy has to falter once again, and I think the second half of 2012 will be just as bad as 2008. The Fed will then revive Quantitative Easing III, but it will not help.

What about the entire concept of paper money?

Paper money is here to stay, but in the near future there will be some kind of gold standard as well, so that money will be partially backed the government’s holding of gold. This way there will be a restraint on the government’s ability to print money.

Any long term investment ideas for our readers? Are you gold bull?

Gold and silver may still be a good investment for 2012, but not for the rest of the decade. However, if there is excessive violence, then the precious metals could shine for a lot longer. I used to be very bullish on gold, but with the metal having appreciated so much already, I am now on the side of caution.

(A shorter version of this interview was pubished in the Daily News and Analysis (DNA) on May 7,2012. Vivek Kaul is a writer and can be reached at [email protected])

What Bihar is to India, INDIA IS TO FOREIGN INVESTORS

Ruchir Sharma is the head of Emerging Market Equities and Global Macro at Morgan Stanley Investment Management. He generally spends one week per month in a developing country somewhere in the world. Also he has been a writer for as long as he has been an investor. Sharma has put his two areas of expertise that of having an extensive experience on emerging markets and being able to write about them, into a new book, Breakout Nations – In Pursuit of the Next Economic Miracle. In this interview he speaks to Vivek Kaul([email protected]).

Excerpts: `

How do you define a breakout nation?

Let me tell you where this idea came from. The last decade was a very exceptional decade for emerging markets in the sense that every developing economy did well. This is not consistent with the history of economic development. We have got two hundred countries in the world, and only 35 are developed, everything else is emerging. So the consistent history of economic growth is that you get bursts of growth and then it falters. Very few countries are able to sustain these bursts of growth and develop and become fully developed countries.

So why was the last decade different?

The 80s and 90s was a very bad period and this was a catch up happening because of that. Also there was a lot of easy money that started to flow out of the United States (US) from 2003 onwards. And there was a boom in the global consumer. It led to this myth at the end of the decade that if you were an emerging market it was all about a time as to when you would converge with the developed world. As I surveyed the world I figured out that’s not going to happen. That’s not the history of economic development and after a decade of economic success many countries were beginning to falter. Other thing that sort of stuck me was that people would ask me, listen even if India grows at 6%, no harm done, because the US is growing at 2-3%. There are two things that are wrong about that argument. One we saw last year, when the Indian equity market fell by 35% in dollar terms last year. So if you undershoot expectations it has a very negative fallout.

You are referring to the Indian GDP growth falling to less than 7%?

Exactly! One thing that people don’t take into account is expectations. Like in China today all expectations are of the country growing by 8-9% and if China grows below 8-9% it leads to instant panic in the markets, especially the commodity markets. So one of the definitions for a breakout nation is that the expectations have to be exceeded. If your expectations are already high and if you are just about meeting them, it’s not going to feel like bang for the buck for anyone.

You say one of the definitions….

The second is this per capita income argument, which is that if India grows at 4-5% that’s a real underachievement because we are only a $1500 per capita income country whereas if a country like Korea grows at 4% it’s a huge achievement because it’s a relatively rich country with a per capita income of more than $20,000. It is still classified as an emerging market but it is fairly rich. So there are three things behind which went into defining what a breakout nation is. One that not all emerging markets are going sort of emerge, so to speak, or become developed markets. Two that expectations are key in terms of how you define a breakout nation and three that you have to take into account per capita income levels. The lower the base the easier it is theoretically to grow and the more you should grow to get out of poverty.

You also say “very few nations achieve long term rapid growth”. Why is that?

This is because most countries or most emerging markets reform only when they have their back to the wall. They enjoy some success and then they stop reforming and begin to fritter away their gains. That’s what happened to Brazil. Brazil used to be the China of the 1960s. Its growth rate was nearly in double digits and then it completely lost its way. It started to fritter it away in terms of huge government spending, subsidies, and massive amount of wasteful expenditure which led to hyperinflation. If you look in the high growth list of the 1950s and 1960s, there were countries like Yemen, Iran and Iraq. The odds of long term success like it is with companies is very low. How many companies are there today which were there thirty years ago, or twenty years ago?

So which are the countries which have grown consistently over the long term?

There are only two countries which have grown over 5% for five decades in a row, South Korea and Taiwan. Only six countries were able at more than 5% for four decades in a row. The list included Hong Kong, Singapore, South Korea, Taiwan and I think there was Malta.

What is it that these countries did differently that other countries did not?

In countries like South Korea, China and Taiwan, they consistently had a plan which was about how do you keep reforming. How do you keep opening up the economy? How do you keep liberalizing the economy in terms of how you grow and how you make use of every crisis as an opportunity. Like Korea was really down in the dumps in 1997-98 crisis. They really had their back to the wall. But they capitalized on the crisis to clean up their balance sheet and to emerge again as an economic powerhouse. It is just about the fact you need to consistently keep reforming and understand that odds are against you. In India’s case what concerns me is the attitude. Listen we will grow by 7%, no matter what happens. That is a given. Now why it is a given, I don’t know. Earlier it was 8-9%. Many businessmen also like to parrot the line that 7% growth will happen, no matter what happens. To me I find that very disturbing. Maybe it is changing now, but till at least a year ago, the attitude was very clear.

You have set many doubts on China becoming a breakout nation. Why?

In fact I admire China’s success and of what they have done over the past thirty years but my point is that expectations on China have become too high. To me that is the big thing. Even though its per capita income has reached around $6000, IMF still thinks that for the next five years the growth will be 8% per annum. Every time the growth dips below 8%, it leads to panic.

Can you elaborate on this?

Surveys are carried out where fund managers are asked will China have a hard landing. I find two responses interesting. Only 10% say that China will have a hard landing. And how do they define a hard landing, a growth rate of 7% or less. The breakout nation concept is that you got to beat expectations. So what I am saying is that if China records a GDP growth rate of 6% next year, trust me it will lead to a lot of panic in many circles.

There are lots of negatives that you point out about China, which we do not tend to here in the normal scheme of things. Like you talk about salaries going up at a very fast pace i.e. wage driven inflation…

Chinese costs have been going up at the rate of 15% per year, and as I argue at the back of the book, the US in fact is now seeing some reshoring (i.e. factories are moving back to America), as we call it. After all the outsourcing and off-shoring the new trend in the US seems to be reshoring because the wage gap is narrowing. It is still there. But the wage gap is narrowing. An anecdote that I found very useful was when one of my portfolio managers went on the ground and the companies told him was that three years ago we could shout at the workers but today they can shout back at us. I think that’s natural. For the first time in China the urbanization ratio has gone to 50%. So a lot of the workers have moved from rural to urban areas, and the scope of workers left for companies to tap from is diminishing.

Why do you call the $2.5trillion foreign exchange reserves, an illusion?

If you look at the total debt of China as a share of their economy it comes to around 200% of their GDP. The Chinese know that. And therefore they are reluctant now to keep stimulating the economy with debt and they are trying their best to clean up the banking system by sort of being careful about off-balance sheet transactions. When you talk to the entire world, when it comes to debt statistics, they don’t look at the entire picture, they just look at the narrow picture that China’s central government’s debt to GDP is low. But a lot of the debt sits on the local government’s balance sheets or on company balance sheets which are owned by the government, which is all the same if you put it together.

You say that the Chinese consumer not doing well is a big myth…

This is because the Chinese consumer has been doing well. And this myth has got propagated because the Chinese consumption as a share of their GDP is low. But my entire point is that it is low not because consumption is doing badly but because investment and exports have done exceedingly well. My entire point is that the Chinese consumption growth cannot increase further. It can continue at this pace.

I was surprised when I read that the consumer spending in China has been growing in China by 9% every year over the last thirty years.

Yes. It is comparable to what Japan, China and Korea achieved.

So it’s been growing as fast as the Chinese economy…

No. Just a bit below. The Chinese economy has been growing at 10% and the consumption has been growing at 9%. Because the overall economy has grown at 10% and the consumption has grown at 9%, consumption as a share of Chinese GDP has come down, which leads many people to believe that the Chinese consumer is suppressed. Yeah, maybe suppressed relative to exports and investments but not in absolute terms.

Another thing I found quite fascinating in your book is the portion where you describe your experience of taking the maglev train in Shanghai. Can you take us through that?

It was like going to an amusement park. I had heard so much about this train which travels at 400 kilometres an hour. I never thought of taking it because typically someone is there to pick me up at the airport. In 2008, when I was driving from the airport back to my hotel, I heard this train zipping past me like zip. I was like what is this going on? It really feels like a bullet passing you by when you are going by the car. So I decided I have got to try this thing out. When we tried it out, it was a fascinating experience though you have to go out of the way to take the train. In the business class cabin there was nobody else there other than me and my colleague. And you have this fancy stewardess who comes and sort of buys the ticket for you. When you are on the train because it’s a levitation act you just feel zero friction. Outside the train zips past you, but inside you don’t feel as if anything is going on. It’s completely still.

But what is the broader point you were trying to make through this example?

The broader point is that no other country in the world will think of experimenting like this. But they have been investing at such a huge pace that they try out these experiments as well. When I asked why has this not been replicated in other parts of China, and I got all sorts of explanations. One was that now we get environmental protests because it goes through very close to some of the places. This is very new to China that you have got people who are protesting and saying we don’t what this to happen. The fact they are not extending this train to everywhere because it does not make logical sense from the economic point of view. This shows the Chinese thinking also that listen that how much can we keep spending on these things.

You call India and Brazil very high context societies. What is that?

This is a term that the anthropologist Edward Hall came up with. It would always strike me when I went to India and Brazil about the commonalities between the two countries. Someone says you come for dinner and the dinner won’t start till 9.30-10pm. And everyone sort of came late. I go to Brazil every year and in 2008 I heard about this serial called A Passage to India which was a huge hit in Brazil. People were talking about it in the party circles and I was like I want to see this serial. I figured out that it is a soap opera, and people are hooked to it at nine o clock at night. The whole thing is a love story set in Jodhpur and Agra, and the actors were all Brazilians in Indian garb, and they looked pretty much North Indian to me.

The latest item girl in Bollywood is a Brazilian…

Really? You can’t make out the difference very often. And that’s my entire point. There are many parallels. So all this was fun but what was the economic point coming out of it? I hope India does not go down the Brazil way with similar cultural habits of having a welfare state where you want to protect people. At that point of time the government spending in India was beginning to really take off and now it’s clearly sort of very high.

You even hint at India going the Brazilian way of hyperinflation…

This thing of having minimum wages and having them indexed to inflation, all these are traits through which a country like Brazil went down. The fact is that we have found inflation to be more sticky than it should be. This is happening because of all these welfare schemes being put into place. My whole thing is that you just can’t take this for granted. But just because it hasn’t mattered in the past does not mean that it won’t matter in the future.

What is your view on the S&P’s change in outlook on India?

It’s consistent with the fact that we need to obviously get these things under control before we begin to lose the plot.

You also say in the book that India has too many billionaires given its size. What is the point you are trying to make there?

Wealth needs to be celebrated. It is an integral part of a capitalistic society to have billionaires. But when I look at the number of billionaires we have in comparison to the rest of the world, it does seem a bit high. If we had new wealth being created and had new billionaires coming up, that would be a healthy sign. But if it is the same set of people holding onto their wealth, it is not a healthy sign. In the last five years the churn has gone down in comparison to what used to be. And you want high churn to take place because you know then new people are coming in. Also you want billionaires to come from industries which are celebrated because of the general entrepreneurial talent like technology, manufacturing etc, and not from places where the government is issuing licenses . If you look at other countries which have a high share of billionaires compared to the size of their economies they are all countries where cronyism is rampant. Like Russia and Malaysia. And if you look at the countries which have made economic success models in the past, the wealth of the billionaires as a share of their economy is relatively low. This is because to create up an environment conducive for the opening up of the economy, for reform and for wealth generation, you have to have this perception that it is being done in a fair manner.

Can India be a breakout nation?

I think so. I give India a 50:50 chance because expectations have now become lower to 6-7% GDP growth and that at least lowers the bar from growing at the rate of 8-9%, which is a very high bar. Most countries I have categorical stand which is I like I don’t think that Russia and Brazil are on my list of breakout nations. It is a clearly a negative take on them. There is relatively positive take on many of the South East Asian countries and Eastern European countries. But I think in India I am sort of caught in the middle. I see the positives taking place when I travel outside of Delhi, I go to the states. The whole India chapter in the book is about the fact that as the Southern States have dropped off in the growth statistics, but the Northern States which you never thought would do well, from Bihar to even Chattisgarh, are doing well.

I have lived in Bihar for almost 20 years. It is growing from a very very low base, and that’s why the high rate of growth.

Exactly. That is my point on India to you, which is that India’s biggest benefit for becoming a breakout nation is the fact that its base is so low. It is true of India. So what you say of Bihar in an Indian context is true of India in a global context, which is what gives India a 50:50 chance even though the policy makers keep messing it up at the top. As you know with Bihar the base has always been low. But obviously something has happened in the last seven years that the state has started to change.

In the last section of your book you talk about something called the commodity.com. What is that?

My whole point is that the world has developed for years and years and centuries and commodities have followed a very predictable pattern, which is that they go up for one decade and they go down for two decades because new technology, human ingenuity always come up triumph any demand burst that comes through. Yet at this stage all people think that commodities are in some sort of a super cycle that And one sort of stunning statistic that stood out for me is that in 2001 the world has twenty nine billionaires in the energy industry, seventy five in tech. By 2011, the situation had reversed, with thirty-six in tech and ninety one in energy, mostly in oil.

What is the point you are trying to make?

Why should you have so many billionaires out of commodities because all you are doing is digging dirt out of the ground? You are not doing something that is really smart and innovative. This is complete nonsense when you have so many billionaires coming out this sector. You can have a few. These are signs at the peak of any trend when it looks like that this trend is going to go on forever. But those lofty expectations have their own undoing. Along with all this comes my argument that China’s growth is about to graduate to a lower plane. And China is the 800 pound gorilla of the commodity market.

Why do you see the China-commodity connection falling apart soon?

Basically everyone says that China has to grow so it needs commodities. My point is again about expectations. If China’s growth falls to 6-7% as I think it may on a medium term basis, a lot of the investments, a lot of things will appear to be excessive. So China may grow but the demand for commodities could come of very significantly. So steel, copper etc could all face oversupply in the coming years.

One of the things you talk about in your book is that while central banks can print all the money they want, they can’t dictate where it goes…

Exactly. Even in India this whole sort of thing spread…and till date I get some of these questions that we have all this liquidity in the world, central banks are pumping it, you know it has to come here in search of opportunities where else is it going to go. And my point is that it can go into all sorts of wrong places like a lot of it has gone into oil, lot of it has gone into commodities, has gone into people buying fancy wine, luxury goods, gold etc Central banks have put all that money out there because they want growth to revive that the reason for doing it. But you can’t control it. You don’t know where it ends up.

(Vivek Kaul is a writer and can be reached at [email protected]. A slightly different version of the interview appeared in the Daily News and Analysis, April 30, 2012)

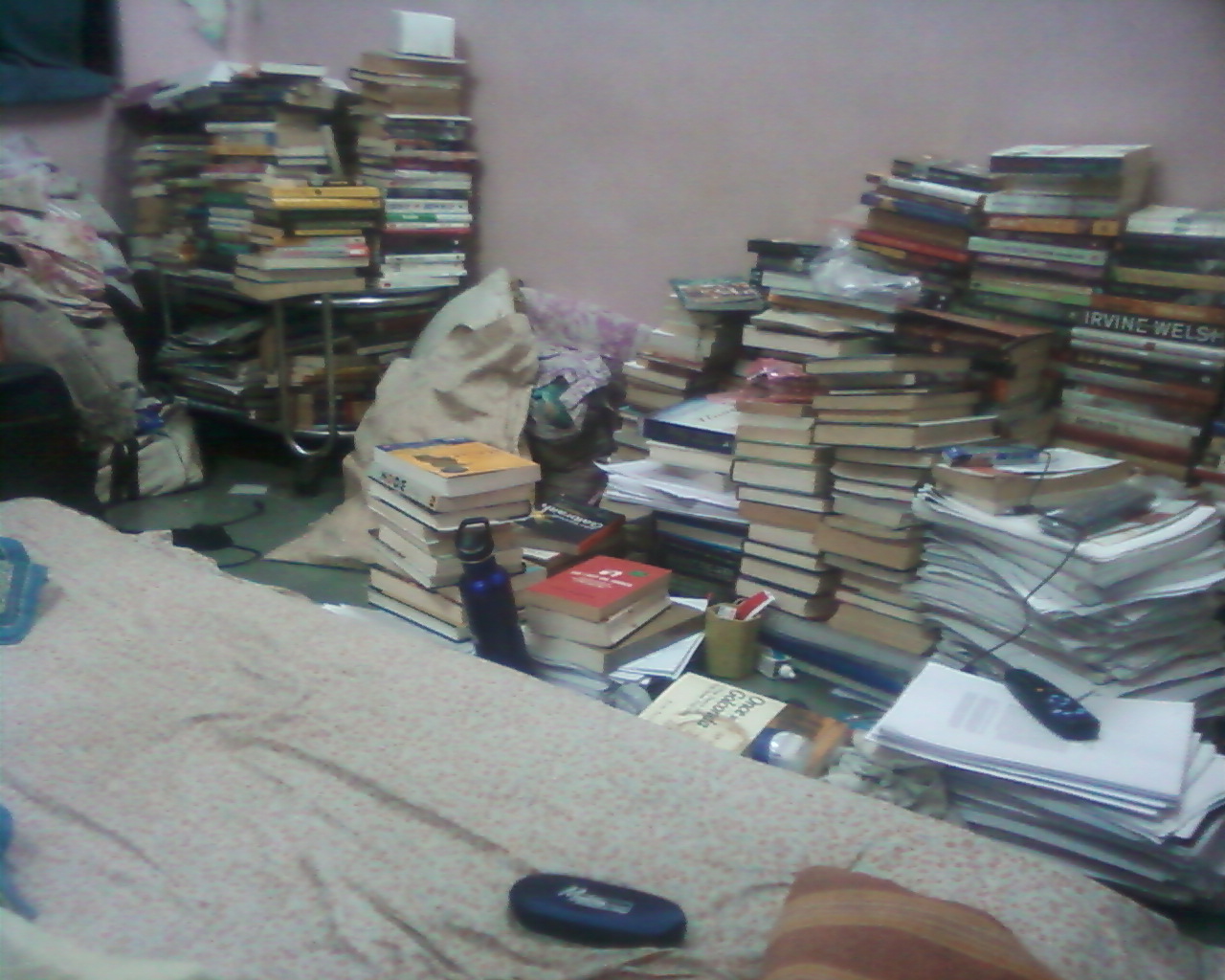

one room kitchen

किताबें इधर उधर पड़ी हुई,

और कुछ तकिये इधर उधर फेके हुए.

कपडे जो धोने के लिए रखे हैं,

और कुछ जो धुले पड़े हैं.

अख़बार के पन्ने जो तेज़ पंखे की वजह से उड़ से जा रहे हैं,

और मेरे कलम जो इधर उधर ठोकर खा रहे हैं.

उस कोने में पड़ा है तुम्हारा jeans पैंट,

और इस कोने में पड़ा है एक महंगा scent

यहीं कहीं है तुम्हारे pink earrings,

जो इस भीड़ में कहीं खो से गए हैं.

और यहीं कहीं है मेरे चश्मे का डब्बा,

जो उन्हें कई दिनों से खोज रहा है.

इन सब के बीच,

सिर्फ एक सफ़ेद टी-शर्ट में लिपटी तुम,

Virginia Woolf की किताब में न जाने कहाँ हो गुम.

चादर रहित गददे पर लेटी हुई,

अपने दायें पाँव के अंगूठे से मेरे कान को सेहला रही हो,

इतने नज़दीक हो कर भी,

मेरे और करीब आ रही हो.