Aswath Damodaran is one of the world’s premier experts in the field of equity valuation. He has written several books like Damodaran on Valuation, Investment Fables, The Dark Side of Valuation and most recently The Little Book of Valuation: How to Value a Company, Pick a Stock and Profit, on the subject. He is a Professor of Finance at the Stern School of Business at New York University where he teaches corporate finance and equity valuation. . In this interview he speaks to Vivek Kaul.

How did you get into the field of valuation?

I started in finance as a general area and then I got interested in valuation when I started teaching. Valuation is a piece of almost everything you do and I was surprised how ill developed it was as a field of thought. It was almost random and not much thinking had gone into thinking about how to do it systematically.

A lot of valuation is basically compound interest when you discount the expected cash flows. So how much of it is math and how much of it is art?

Much of it is not the compound interest or the discount factor it is really the cashflows you have to estimate. So most of it is actually is in the numerator. It is about figuring out what business you are in. Figuring out how you make money. Figuring out what the margins are. What the competition is going to be. So numerator is where all the action is and it is actually very little to do with mathematics. It is more an understanding of business and actually getting it into numbers.

Can you give us an example?

So if you are trying to value Facebook getting the discount rate for Facebook is trivial. It is easy. It is about 11.5%. It is about the 80th percentile in terms of riskiness of companies. The trouble with Facebook is figuring out, first what business they are going to be in, because they haven’t figured it out themselves. How are they going to convert a billion users into revenues and income? And second, if they even manage to do it, how much those revenues will be, what will the margins etc. And those are all functions where you cannot think just Facebook standing alone. It is going to compete against Google. It is going compete against Apple. It is going to compete against other social media companies. So you have to make judgement calls of how it is all going to play out. It is numbers but the numbers come from understanding business. Understanding strategy. Understanding competition. Understanding all the things that kind of come into play.

You just mentioned that the discounting rate for expected cash flows from Facebook was at 11.5%. How did you arrive at that?

I have the cost of capital for by every sector in the US.

So this is the cost of capital for dotcoms?

This is actually the cost of capital for risky technology capitals. So basically I am saying is that I could sit there and try to finesse it and say is it 11.8% or is it 11.2%. But it doesn’t really matter. Getting the revenues and margins is more critical than getting the discount rate narrowed down.

This 11.5% would be from a combination of equity and debt?

For a young growth company it is almost going to be all equity. You don’t borrow money if you are that small and when you are in a high growth phase it is not worth it. It is almost all equity.

I recently read a blog of yours where you said that you have sold Apple shares even though they were undervalued. Why did you do that?

There are two parts to the investment process. One is the value part to the process. And the other is the pricing part to the process. To make money you need to be comfortable with both parts. You want to feel comfortable with value and you have to feel comfortable that price is going to converge on the value. In the case of Apple for 15 years I was comfortable with my estimate of value and I was comfortable that the price would converge on value. In the last year the Apple stockholder base has had a fairly dramatic change. There has been influx of a lot of institutional investors who have coming in as herd investors and momentum investors who go wherever the price is hottest. You have also got a lot of dividend investors who came in last year because they expected Apple to start paying dividends.

What happened because of that?

So you got this influx of new investors with very different ideas of what they expect Apple to do in the future. They are all in there. And right now they are okay for the moment because Apple is able to keep them all reasonably happy. But I think this is a game where I have lost control of the pricing process because those investors turn on a dot. Like they did, when the stock went from $640 to $530 for no reason at all. You look at any news that came out. Nothing came out. So why is the stock worth $640 and eight weeks later $530? But that’s the nature of momentums stocks. It is not news that drives the price anymore, it’s the herd. Basically if it moves in one direction, prices are going to go up $20. If it moves in the other direction, it is going to go down $30. And I looked at the pricing process and said I have lost control of this part of the process. I am comfortable with the value still. But I am leaving not forever. If these guys keep pushing it down, sooner or later they are going to push it to a point where these guys leave and then I can step in buy the stock. So it’s not permanent but I think at the moment it has become a momentum stock.

You have talked about the danger of purely relying on stories while investing. But that’s how most investors invest. What are the problems with that?

Even momentum investors want a crutch. Basically stories give them a crutch. You have decided to buy the stock anyway because everyone else is doing it. You don’t want to tell people because that doesn’t sound good so you look for a story to convince yourself that you area really doing this for a good reason. The power of the story is very strong, I am not denying it. But I am saying that if there is a story my job is to bring it into the numbers and see if that story holds up to scrutiny.

Any example?

You can talk about user base. Facebook the story is that they have lots of users. My job is to take those billion users and talk about what that might mean in revenues and margins and operating income and cash flows. And not just say that there are lot of users therefore the company must be worth a lot. If a Chinese company says we are going to be valued. There are a billion Chinese. Okay. What does that mean? You have a billion Chinese but how much will be you able to sell? How much will they buy your product? So I think you need to get past the macro big story telling because it is easy to fall into saying that hey this company is worth a lot.

Can smaller investors make money by piggybacking on investment decisions of big investors?

If you look at institutional investors they do things so badly why do you want to piggyback on them.

Someone like a Warren Buffett and Rakesh Jhunjhunwala in the Indian context?

You could but I think by the time you get the information it is usually too late. It is not like you are the only one who finds out that Warren Buffett has bought a stock. Half the world has found out. So when you get to lineup to buy the stock, everyone else is buying the stock and price has already moved up.

George Soros once said that most money is made by entering a bubble early. What are your views on that?

Everybody is guilty of hyperbole when it comes to bubbles and Soros is no exception. Soros has never been a great micro investor. He has made his money on macro bets. He has always been. He has never been a great stock picker. For him it is got to be massive macro bubbles, an asset class that gets overpriced or underpriced. You’re right if you can call macro bubbles you can make a lot of money. John Paulson called the housing bubble made a few billion dollars. So he is right and he is wrong. He is right because if you can call a macro bubble you can make a lot of money. He is wrong because if you make your investment philosophy calling macro bubbles, you better get lucky, because everybody is calling macro bubbles and most of them are going to be wrong.

You have talked about buying the 35worst stocks in the market and holding that investment and making money on it. How does that work?

It’s called the classic contrarian investment strategy where you buy the biggest holders and you hold them for a long period. There is evidence that if you hold them for a long period that they tend to be the best investments. But it comes with caveats. One is that if you buy the 35 biggest losers they often tend to be low priced stocks because they have gone down so much which increases the transaction cost of your trading. The other is that it is very dependant on your time horizon. It turns out that if you buy the lowest price stocks for the first 18 months they actually underperform. It is only after that they turnaround. This means that if you buy these stocks you are going to get about 18 months of heart burn and stomach aches. And for many people they don’t have the patience to stay in. So they often buy the worst stocks after reading these studies. About 12 months in they lose patience they sell it. It is very dependant on both those pieces of puzzle falling in.

How much role does media play in influencing investment decisions of people?

Media and analysts are followers. None of the media told us last week that Facebook was going to collapse. Now of course everybody is talking about it. So basically when I see in the media news stories I see a reflection of what has already happened. It is a lagging indicator. It is not a leading indicator. I have never ever found a good investment by reading a news story. But I have heard about why an investment was good in hindsight by reading a news story about it.

I am not a great believer that I can find good investments in the media. That’s not their job anyway.

(The interview was originally published in the Daily News and Analysis(DNA) on June 2,2012. http://www.dnaindia.com/money/interview_ive-never-found-a-good-pick-by-reading-a-news-story_1696935)

(Vivek Kaul is a writer and can be reached at [email protected])

No, Subbarao won’t be able to clean UPA’s garbage dump

Vivek Kaul

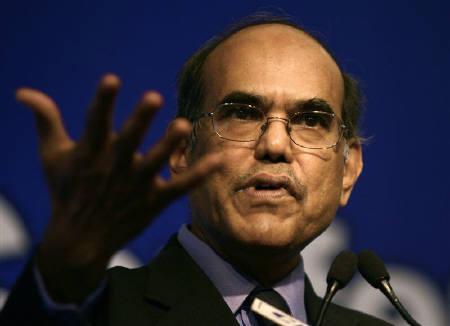

Duvvuri Subbarao, the current governor of the Reserve Bank of India must be a troubled man these days, professionally that is. The gross domestic product (GDP) growth has fallen to 5.3% for the period of January to March 2012. And now he is expected to come to the rescue of the Indian economy by cutting interest rates, so that people and businesses can easily borrow more, and we all can live happily ever after.

Cows would fly, only if it was as simple as that!

The mid quarter review of the monetary policy is scheduled for June 18,2012. On that day the Subbarao led Reserve Bank of India(RBI) is expected to cut the repo rate by at least 50 basis points (one basis point is one hundredth of a percentage). The repo rate is the rate at which banks borrow from the RBI.

Repo rate is a short term interest rate and by cutting this interest rate the RBI tries to manage the other interest rates in the economy, including long term interest rates like the rate at which the bond market lends to the government, the interest offered by banks on their fixed deposits, and the interest charged by banks on long term loans like home loans, and loans to businesses.

But the fact of the matter is it really has no control on these interest rates in the current state of things. To understand why, let us deviate a little.

Greenspan and Clinton

Alan Greenspan and Bill Clinton came from the opposite ends of the political spectrum. Greenspan had been a lifelong Republican whereas Clinton was a Democrat. Unlike India where there are a large number of political parties, America has basically two parties, the Republican Party and the Democratic Party. Greenspan was the Chairman of the Federal Reserve of United States, the American central bank, from 1987 to 2006.

But despite coming from the opposite ends of the political spectrum they got along fabulously well. In fact, when Clinton became the President of America in early 1993, Greenspan approached him with what Americans call a “proposition”.

Greenspan told Clinton that since 1980 the rate of inflation had fallen from a high of around 15% to the current 4%. But during the same period the interest rate on home loans had fallen only by 400 basis points from 13% to 9%. Despite the fact that the Federal Funds Rate (the American equivalent of the Indian repo rate) stood at a low 3%.

Why was the difference between the Federal Funds rate which was a short term interest rate and the home loan interest rate, which was a long term interest rate, so huge?

High fiscal deficit

The difference in interest rates was primarily because of the high fiscal deficit that the government of United States was incurring. Fiscal deficit is the difference between what the government earns and what it spends in a particular year.

When Clinton took over as President on January 20, 1993, the American government had just run a record fiscal deficit amounting to $290.3billion or 4.7% of the GDP for 1992. And this had led to high long term interest rates even though the Federal Reserve had set the short term Federal Funds rate at 3%.

The government was borrowing long term to fund its fiscal deficit. And since its borrowing needs were high because of the large fiscal deficit it needed to offer a higher rate of interest to attract lenders. When the government borrowed more it crowded private borrowing, meaning, there was lesser pool of “savings” for the private borrowers to borrow from.

Hence, banks and other financial institutions which needed to borrow in order to give out home loans had to offer an even higher rate of interest than the government to attract lenders. Even otherwise, the private sector has to offer a higher rate of interest than the government, because lending to the government is deemed to be the safest form of lending. Due to these reasons the difference in short term interest rates and long term interest rates in the US was high. So the repo rate was at 3% and the home loan rate was at 9%.

The proposition

Greenspan was rightly of the opinion that a high fiscal deficit was holding economic growth back. This was the argument he made to President Clinton when he first met him. As Greenspan writes in his autobiography The Age of Turbulence – Adventures in a New World “Long term interest rates were still stubbornly high. They were acting as a brake on economic activity by driving up costs of home mortgages (the American term for home loans) and bond issuance.”

Other than the government which issues bonds to finance its fiscal deficit, companies also issue bonds to raise debt to meet the needs of their business. If interest rates are high companies normally tend to put expansion plans on hold because high interest rates may not make the plan financially viable.

Greenspan’s proposition to Clinton was that if the Wall Street got enough of a hint that the government was serious about bringing down the fiscal deficit, long term interest rates would start to fall . This would be good for the overall economy because at lower interest rates people would borrow more to buy houses and as well as everything else that needs to be bought to make a house a “home”.

As Greenspan writes “Improve investors’ expectations, I told Clinton, and long-term rates could fall, galvanizing the demand for new homes and the appliances, furnishings, and the gamut of consumer items associated with home ownership. Stock values too, would rise, as bonds became less attractive and investors shifted into equities.”

The US Congressional and Budget Office(CBO), a US government agency which provides economic data to the US Congress (the American parliament) to help better decision making, upped its projection of the fiscal deficit at that point of time. It said that the fiscal deficit is likely to reach $360billion a year by 1997. This data point put out by the US CBO helped buttress Greenspan’s point further and Clinton decided to do something about the fiscal deficit.

The Clinton plan

Clinton put out a plan which would cut the deficit by $500billion over a period of four years through a combination of higher tax rates as well as lower spending by the government. The fiscal deficit of the United States of America which had been growing steadily for years, started to fall from 1993. In 1993, it was down by 12% to $255billion. By 1997, the fiscal deficit was down to $21billion. In Clinton’s second term as President, the deficit turned into a surplus, something that had not happened since 1971. Between 1998 and 2001, the US government earned a surplus of $559.4billiondollars.

A lower fiscal deficit led to lower long term interest rates and good economic growth. The United States of America grew at an average rate of 3.9% between 1993 and 2000. In the eight years prior to that the country had grown at an average rate of 2.9% per year. So the US grew at a much faster rate on a higher base because the fiscal deficit was turned into a fiscal surplus.

This was also the period of the dotcom bubble but the fiscal surplus was clearly not the reason for it.

The moral of the story

As we clearly see from the above example, at times there is not much that a central bank can do on the interest rate front, especially when the government is running a high fiscal deficit. As I have often said over the past one month the fiscal deficit of the government of India has increased by 312% between 2007 and 2012. During the same period its income has increased by only 36%. The fiscal deficit target for the current financial year is at Rs Rs 5,13,590 crore, a little lower from the last year’s target. But as we have seen in the past this government has a tendency to miss its fiscal deficit targets regularly. So the government will have to borrow to finance its fiscal deficit and that means an environment in which long term interest rates will remain high.

In fact, some banks have quietly raised the interest rates they charge to their existing home loan borrowers, after the Subbarao led RBI last cut the repo rate by 50 basis points on April 17, 2012.

The interest being charged to some of the existing home loan borrowers has even crossed 14.5%, a difference of more than 6% between a long term interest rate and the repo rate, as was the case in America.

India has another problem which America did not in the early 1990s, high inflation. The consumer price inflation was at 10.36% for the month of April 2012. Urban inflation was at 11.1% whereas rural inflation was just below 10% at 9.86%. If Subbarao goes about cutting the repo rate in a rapid manner, he runs the danger of inciting further inflation.

So the only way out of this mess is to cut subsidies. Cut fuel subsidies. Cut fertilizer subsidies. This of course would mean higher prices in the short term, particularly if diesel prices are raised. An increase in the price of diesel will immediately lead to higher inflation, given that diesel is the major transport fuel, and any increase in its price is passed onto the consumers. The government thus has to make a choice whether it wants high interest rates for the long term or high inflation for the short term. It need not be said it will be a politically difficult decision to make.

Over the longer term it also needs to figure out how to bring more Indians under the tax ambit and lower the portion of the “black” economy in the overall economy. (You can read this in detail here: It’s not Greece: Cong policies responsible for rupee crashhttp://www.firstpost.com/economy/dont-blame-greece-cong-policies-responsible-for-rupees-crash-318280.html)

And there is nothing that RBI can do on any of these fronts. The predicament of the RBI was best explained in a recent column titled Seeking Divine Intervention, written by Rajeev Malik, an economist at CLSA. He said: “There are three institutions that keep India running: the Supreme Court, the Election Commission and the Reserve Bank of India (RBI). To be sure, most of the economic mess in India has the government behind it. And often the RBI is called in as a vacuum cleaner. But even the world’s best vacuum cleaner cannot be successfully used to clean up a garbage dump.”

(The article originally appeared at www.firstpost.com on June 4,2012. http://www.firstpost.com/economy/no-subbarao-wont-be-able-to-clean-upas-garbage-dump-331114.html)

(Vivek Kaul is a writer and can be reached at [email protected])

Sonia’s UPA is taking us to new ‘Hindu’ rate of growth

Vivek Kaul

Raj Krishna, a professor at the Delhi School of Economics, came up with the term “Hindu rate of growth” to refer to Indian economy’s sluggish gross domestic product (GDP) growth of 3.5% per year between the 1950s and the 1980s. The phrase has been much used and abused since then.

A misinterpretation that is often made is that Krishna used the term to infer that India grew slowly because it was a nation dominated by Hindus. In fact he never meant anything like that. Krishna was a believer in free markets and wasn’t a big fan of the socialistic model of development put forward by Jawahar Lal Nehru and the Congress party.

In fact he realised over the years looking at the slow economic growth of India that the Nehruvian model of socialism wasn’t really working. This was visible in the India’s secular or long term economic growth rate which averaged around 3.5% during those days.

The word to mark here is “secular”. The word in its common every day usage refers to something that is not specifically related to a particular religion. Like our country India. One of the fundamental rights Indians have is the right to freedom of religion which allows us to practice and propagate any religion.

But the world “secular” has another meaning. It also means a long term trend. Hence when economists like Krishna talk about the secular rate of growth they are talking about the rate at which a country like India has grown year on year, over an extended period of time. And this secular rate of growth in India’s case was 3.5%. This could hardly be called a rate of growth for a country like India which was growing from a very low base and needed to grow at a much faster pace to pull its millions out of poverty.

So Krishna came up with the word “Hindu” which was the direct opposite of the word “secular” to take a dig at Jawahar Lal Nehru and his model of development. Nehru was a big believer in secularism. Hence by using the word “Hindu” Krishna was essentially taking a dig on Nehru and his brand of economic development, and not Hindus.

The policies of socialism and the license quota raj followed by Nehru, his daughter Indira Gandhi and grandson Rajiv ensured that India grew at a very slow rate of growth. While India was growing at a sub 4% rate of growth, South Korea grew at 9%, Taiwan at 8% and Indonesia at 6%. These were countries which were more or less at a similar point where India was in the late 1940s.

The Indian economic revolution stared in late July 1991, when a certain Manmohan Singh, with the blessings of PV Narsimha Rao, initiated the economic reform process. The country since then has largely grown at the rates of 7-8% per year, even crossing 9% over the last few years.

Over the years this economic growth has largely been taken for granted by the Congress led UPA politicians, bureaucrats and others in decision making positions. Come what may, we will grow by at least 9%. When the growth slipped below 9%, the attitude was that whatever happens we will grow by 8%. When it slipped further, we can’t go below 7% was what those in decision making positions constantly said. On a recent TV show Montek Singh Ahulwalia, the Deputy Chairman of the Planning Commission, kept insisting that a 7% economic growth rate was a given. Turns out it’s not.

The latest GDP growth rate, which is a measure of economic growth, for the period of January to March 2012 has fallen to 5.3%. I wonder, what is the new number, Mr Ahulwalia and his ilk will come up with now. “Come what may we will grow at least by 4%!” is something not worth saying on a public forum.

But chances are that’s where we are headed. As Ruchir Sharma writes in his recent book Breakout Nations – In Pursuit of the Next Economic Miracles “India is already showing some of the warning signs of failed growth stories, including early-onset of confidence.”

The history of economic growth

Sharma’s basic point is that economic growth should never be taken for granted. History has proven otherwise. Only six countries which are classified as emerging markets by the western world have grown at the rate of 5% or more over the last forty years. These countries are Malaysia, Singapore, South Korea, Taiwan, Thailand and Hong Kong. Of these two, Hong Kong and Taiwan are city states with a very small area and population. Hence only four emerging market countries have grown at a rate of 5% or more over the last forty years. Only two of these countries i.e. Taiwan and South Korea have managed to grow at 5% or more for the last fifty years.

“In many ways “mortality rate” of countries is as high as that of stocks. Only four companies – Procter & gamble, General Electric, AT&T, and DuPont- have survived on the Dow Jones index of the top-thirty U.S. industrial stocks since the 1960s. Few front-runners stay in the lead for a decade, much less many decades,” writes Sharma.

The history of economic growth is filled with examples of countries which have flattered to deceive. In the 1950s and 1960s, India and China, the two biggest emerging markets now, were struggling to grow. The bet then was on Iraq, Iran and Yemen. In the 1960s, the bet was Philippines, Burma and Sri Lanka to become the next East Asian tigers. But that as we all know that never really happened.

India is going the Brazil way

Brazil was to the world what China is to it now in the 1960s and the 1970s. It was one of the fastest growing economies in the world. But in the seventies it invested in what Sharma calls a “premature construction of a welfare state”, rather than build road and other infrastructure important to create a viable and modern industrial economy. What followed was excessive government spending and regular bouts of hyperinflation, destroying economic growth.

India is in a similar situation now. Over the last five years the Congress party led United Progressive Alliance is trying to gain ground which it has lost to a score of regional parties. And for that it has been very aggressively giving out “freebies” to the population. The development of infrastructure like roads, bridges, ports, airports, education etc, has all taken a backseat.

But the distribution of “freebies” has led to a burgeoning fiscal deficit. Fiscal deficit is the difference between what a government earns and what it spends.

For the financial year 2007-2008 the fiscal deficit stood at Rs 1,26,912 crore against Rs 5,21,980 crore for the current financial year. In a time frame of five years the fiscal deficit has shot up by nearly 312%. During the same period the income earned by the government has gone up by only 36% to Rs 7,96,740 crore. The huge increase in fiscal deficit has primarily happened because of the subsidy on food, fertilizer and petroleum.

This has meant that the government has had to borrow more and this in turn has pushed up interest rates leading to higher EMIs. It has also led to businesses postponing expansion because higher interest rates mean that projects may not be financially viable. It has also led to people borrowing lesser to buy homes, cars and other things, leading to a further slowdown in a lot of sectors. And with the government borrowing so much there is no way the interest rate can come down.

As Sharma points out: “It was easy enough for India to increase spending in the midst of a global boom, but the spending has continued to rise in the post-crisis period…If the government continues down this path India, may meet the same fate as Brazil in the late 1970s, when excessive government spending set off hyperinflation and crowded out private investment, ending the country’s economic boom.”

Where are the big ticket reforms?

India reaped a lot of benefits because of the reforms of 1991. But it’s been 21 years since then. A new set of reforms is needed. Countries which have constantly grown over the years have shown to be very reform oriented. “In countries like South Korea, China and Taiwan, they consistently had a plan which was about how do you keep reforming. How do you keep opening up the economy? How do you keep liberalizing the economy in terms of how you grow and how you make use of every crisis as an opportunity?” says Sharma.

India has hardly seen any economic reform in the recent past. The Direct Taxes Code was initiated a few years back has still not seen the light of day, but even if it does see the light of day, it’s not going to be of much use. In its original form it was a treat to read with almost anyone with a basic understanding of English being able to read and understand it. The most recent version has gone back to being the “Greek” that the current Income Tax Act is.

It has been proven the world over that simpler tax systems lead to greater tax revenues. Then the question is why have such complicated income tax rules? The only people who benefit are CAs and the Indian Revenue Service officers.

Opening up the retail sector for foreign direct investment has not gone anywhere for a long time. This is a sector which is extremely labour intensive and can create a lot of employment.

What about opening up the aviation sector to foreigners instead of pumping more and more money into Air India? As Warren Buffett wrote in a letter to shareholders of Berkshire Hathaway, the company whose chairman he is, a few years back “The worst sort of business is one that grows rapidly, requires significant capital to engender the growth, and then earns little or no money. Think airlines. Here a durable competitive advantage has proven elusive ever since the days of the Wright Brothers. Indeed, if a farsighted capitalist had been present at Kitty Hawk, he would have done his successors a huge favor by shooting Orville down…The airline industry’s demand for capital ever since that first flight has been insatiable. Investors have poured money into a bottomless pit, attracted by growth when they should have been repelled by it.”

If foreigners want to burn their money running airlines in India why should we have a problem with it?

The insurance sector is bleeding and needs more foreign money, but there is a cap of 26% on foreign investment in an insurance company. Again this limit needs to go up. The sector very labour intensive and has potential to create employment. The same is true about the print media in India.

The list of pending economic reforms is endless. But in short India needs much more economic reform in the days to come if we hope to grow at the rates of growth we were growing.

To conclude

Raj Krishna was a far sighted economist. He knew that the Nehruvian brand of socialism was not working. It never has. It never did. And it never will. But somehow the Congress party’s fascination for it continues. And in continuance of that, the party is now distributing money to the citizens of India through the various so called “social-sector” schemes. If economic growth could be created by just distributing money to everyone, then India would have been a developed nation by now. But that’s not how economic growth is created. The distribution of money creates is higher inflation which leads to higher interest rates and in turn lower economic growth. Also India is hardly in a position to become a welfare state. The government just doesn’t earn enough to support the kind of money it’s been spending and plans to spend.

Its time the mandarins who run the Congress party and effectively the country realize that. Or rate of growth of India’s economy (measured by the growth in GDP) will continue to fall. And soon it will be time to welcome the new “Hindu” rate of economic growth. And how much shall that be? Let’s say around 3.5%.

(The article originally appeared at www.firstpost.com on June 1,2012. http://www.firstpost.com/politics/sonias-upa-is-taking-us-to-new-hindu-rate-of-growth-328428.html)

(Vivek Kaul is a writer and can be reached at [email protected])

Facebook is a corporate dictatorship.

When the whole world was going gaga about Facebook’s Initial Public Offering (IPO), there was one man who did not fall for all the hype, looked at the numbers of the company, asked some basic questions and concluded “they don’t know how they are going to make money.” Looks like, he was proved right in the end. The stock was sold at a price of $38 per share, and has fallen since then. Aswath Damodaran was the man who got it right. “In hindsight everybody will tell you that they were bearish on Facebook. Nobody will admit to buying the shares,” points out Damodaran. He is a Professor of Finance at the Stern School of Business at New York University where he teaches corporate finance and equity valuation. In some circles he is referred to as the “god of valuation”. In this interview he speaks to Vivek Kaul.

Excerpts:

Let us start with Facebook, you have been critical about their IPO pricing?

The trouble with Facebook is figuring out, first what business they are going to be in, because they haven’t figured it out themselves. How are they going to convert a billion users into revenues and income? And second, if they even manage to do it, how much those revenues will be, what will the margins etc. They don’t know how they are going to make money. Whether they are going sell advertising to these users? Whether they are going to sell products to these users? Services to these users? I think all they know right now is that they have a lot of users.

But if they have no idea of what to do with their users, how did they make the $4billion in sales that they did last year?

They are selling. 12% of that came from selling stuff for Zynga (The maker of popular games such as “FarmVille” and “CityVille,”). The remaining 88% did come from very subtle advertising. The question is that whether they can scale that up? Because right now it is kind of invisible. You can’t see it because it is relatively small. But if they want to generate the kind of revenues they want, you are going to see it on your Facebook page. And it is going to be very very clear that they are using what they know about you to pick those ads. And I am not sure people will be comfortable with that knowing that they are seeing not just your profile but your interactions. So they can see how old you are. What political party your support? What sports you like? It is all going to go. And that’s their selling point.

So it will be some sort of invasion of privacy?

It is not some sort of invasion of privacy. It is an invasion of privacy. The question is can they do that without people getting pissed off and saying I am leaving Facebook and going elsewhere. And that I think is the big unknown. Because let’s face it, they have not just a billion users, but they know more about these users than any other company on the face of this earth. If you want a company to find 35million people who fit a specific demographic characteristic, the place to go is Facebook. They can show it to you. The only question is that if you did advertise through Facebook to those 35million is this the kind of forum were they are inclined to click on an ad.

How does it compare with Google?

In case of Google it is a much more direct business model. It’s search. You click and that’s it, everybody could see what they were doing. Facebook is a much more subtle model. On Facebook you are talking to your friends, which is a private conversation between you and your friends, but when you see these intrusive ads on the side, you realize you are not just talking to your friends, you are talking to your friends and somebody at Facebook is monitoring you at the same time. That’s a very tricky challenge. So they have made the $4billion, but at the value (the market capitalization of the Facebook stock) they have they have to make $35billion. And that’s a very different game because that would mean a lot more ads on every page directly focused in on what the users are doing.

In face very frankly I didn’t realize there are ads on my Facebook page for a long time…

It is pretty subtle right now because they don’t have that much advertising. If you think of revenue of $4billion spread out across a billion users, you are going to see a very few ads because it is still on the sides. And sometimes it doesn’t even look like an ad. Right. It’s a Facebook friend with GM. You click on it and before you know it you are looking at GM’s product offerings. So it is very subtle right now. But it can’t stay subtle for them to make the kind of revenues they have to make to justify their price now. The kind of scary thing here is that Mark Zuckerberg has said that he wants to build a social enterprise and not a business enterprise.

What does he mean by that?

What he means by that is he built Facebook so that people could talk to each other. He didn’t want ads on it. For a long time he refused to take ads on Facebook until he was told that if you can’t take ads there is no other way to make money in this. So I am not sure how willing he is to go the distance because it is going to be a fight. It’s going to be a fight against not other social media companies but against the big players. The Googles and The New York Times of the world. This is a tough game to fight and you got be willing to act like a business and I am not sure is willing to yet.

You called the business model of Facebook, a Field of Dreams. Why is that?

Yeah. You ever seen that movie? Field of Dreams.

No.

In the movie Kevin Costner moves to the American Midwest and he is walking through this cornfield. And hears this voice and it says “if you build it he will come”. He being Shoeless Joe Jackson, a baseball player from a 100 years ago. On the faith that these old baseball players will show up, he builds this baseball field in the middle of Iowa and everybody asks him, why are you building this huge baseball field in the middle of nowhere? And he tells them, if I build it they will come. And that in a sense is what social media companies are doing right now. They are building this place where there are lots of users and they are telling people trust us if we build this, they will come. They being advertisers, product sellers, they will come. But in the Field of Dreams they did come but I am not sure in these companies that they will.

Talking about the current price of Facebook how do you see it? Yesterday is closed at around $33.(The interview was conducted on Thursday, May 24,2012) Has it fallen enough?

I think it fell enough in those two days that you are going to get a consolidation. The next run on them will tell how far they might go back. The low 30s are close enough to my intrinsic value that I wouldn’t call them massively overvalued. I think there is enough potential in the company. If it dropped to $15 then it’s pretty much a bargain. At $31-32 its pretty close to intrinsic value

The intrinsic value you calculated for Facebook was $29?

Yeah.

So why was the stock valued at such a high price of $38 per share when it was sold to the public?

It wasn’t valued. It was priced.

So why was it priced at such a high price?

Remember they weren’t pricing it on a blank slate. They could see transactions happening in the private share market where people were buying and selling Facebook shares. And there the prices were going at about $42-43. So they said if people are buying and selling at this price, these are real transactions.

What sort of stock market was this?

For the last two years Facebook has been on what’s called a private share market where people who owned shares of Facebook were allowed to trade.

So is it like over the counter?

Not even over the counter. They are actually beyond the counter. These are private companies that are not incorporated. So this is a completely unregulated share market. Like Goldman Sachs could sell shares. Players in this market are pretty big institutional investors they are not individual investors. Transactions here have particular merit because these are two informed investors transacting and they are coming to a price. And investment bankers saw that price and they said if they are paying $42, then we should be able to sell it at $38. And they also got onto the phone and they called institutional investors. They tried to gauge demand until Thursday evening (May 17,2012). And that’s why they set the price at 4 o’clock on Thursday because that’s how late they were pushing this off to make sure that there was enough demand.

Wasn’t this a throwback to the days of the dotcom bubble?

This is how all pricing is done in IPOs. IPOs are always priced they are never valued because essentially your job as an investment banker is to sell at that price. What was unusual here was that demand and supply that they gauged collapsed. They didn’t realize how thin the market was until one hour into the offering when they saw the price collapse. It started at $38, it went to $43, and then very quickly it kind of collapsed. My theory is when you price things you are building in market perceptions, what you think will happen etc. You are basing it in on momentum. That’s a very fragile thing. You don’t want mess with it. Even people who are buying based on pricing and momentum like to tell themselves that they are buying based on value. So they look for a good story and they don’t want to have their face rubbed at the fact that they are buying because everybody else is paying the price.

In case of Facebook it was quite the opposite…

If you look at what the investment banks and Facebook insiders did in the last week they almost rubbed the investors faces in this. They rubbed it in the sense that they kept hiking up the offering price, saying we know you are suckers. At the same time the insiders were selling the shares in the week leading up to the offering. If I had been the investment banker I would have spent the last week talking about the user base, and advertising because that would have given the momentum investors a crutch. I am purely buying it because of advertising revenues. Instead it was all about pricing. They made it very transparent that they were not valuing the company. It was all demand and supply. I have a feeling that if you point to midday on Friday (May 18,2012) and say that was the time when the momentum on social media companies, not just on Facebook, shifted. And if you look at what has happened since it is not just Facebook which has seen its price collapse. It’s Groupon. It’s LinkedIn. It’s the entire sector. And I wager that there are IPOs lined up to go to investment banks of social media companies, that are either being pulled right now or being dramatically repriced.

You have said in the past that Facebook has huge corporate governance issues. Can you elaborate on that?

It has got voting shares and non-voting shares. Zuckerberg has got the voting rights. It is also incorporated as a controlled corporation which basically means that you don’t have to follow the corporate governance rules (like the Sarbanes Oxley Act) that publically traded companies need to do. They can have insiders on the board.

Is that allowed?

If you are controlled corporation it is. And Facebook has been very open about that they are going to be a controlled corporation.

How does regulation allow for something like that?

As long as you make it public. If it is a controlled corporation investors have to make a judgement as to whether they care. In case of Facebook initially it looked like they didn’t care. Right from the beginning Facebook has been very open that they are not really going to be a publically traded company and that really they are a private business that wants the capital that public markets give them. But it is going to be Zuckerberg’s company.

So they won’t give out much information?

They might give out the information but you will have no say in what they do. So if they do an acquisition…

Did they overpay for Instagram?

They paid. I don’t know whether they overpaid. But the paid and there was no accountability. Zuckerberg basically decided to pay a billion (dollars) then he told the board that I have bought the company and I have paid a billion. This is not the way a company should be bought. A CEO shouldn’t be deciding what to pay overnight and you shouldn’t be telling the board of directors after you have bought a company that I just bought a company for a billion and I just want you to know.

This is like how mom and pop shops down the road operate…

It is a way a dictatorship operates. Facebook is a corporate dictatorship.

So who influenced Zuckerberg to do what he is doing?

Google set the framework that Facebook is using right now. The voting shares, non-voting shares. Sergey Brin and Larry Page are the models that Zuckerberg is using.

Can you elaborate on that?

Until Google came along, US companies generally did not have two classes of shares. Voting shares and nonvoting shares were for a long time banned by the New York Stock Exchange. So most companies didn’t even try. So if you look at Apple, you look at Microsoft they had only one class of shares. Google essentially did two things. They did their IPO through an auction rather than through investment banks. And secondly they decided to have voting and nonvoting shares. If institutional investors had risen at that point of time and said we are not buying these shares because we don’t have enough voting rights, then Google would have been forced to go back to drawing board and then come back. Institutional investors were okay with Google doing that. Once they opened that door every social media company you look at LinkedIn and Groupon, they follow what Google did.

So these shares are listed on NASDAQ?

Yes. NASDAQ allows for voting and nonvoting shares that is the part of the reason for listing on it. The New York Stock Exchange because it is in competition with NASDAQ has now also started relaxing, they want the money, they want the listings. So they will take Facebook even if it’s voting and nonvoting shares. So this will be a race to the bottom.

So the shares sold to the public were nonvoting shares?

They are low voting shares. The shares that Zuckerberg owns have 10 times the voting rights, which means he has 57% of voting rights with 35% of the shares. And he will always make sure that remains above 50%.

So he can go ahead and buy anything without requiring clearance from the board?

Google for instance recently issued new shares which have no voting right at all. So that is the third layer. You have ten voting rights shares. One voting rights shares. And no voting rights shares. Zuckerberg can go out and raise as much capital as he wants. If he issues no voting rights he will always have 57%. He going to lock in that voting percentage.

But how is something like this allowed in a developed market like the US?

I don’t think it should be banned. Let the investors decide for themselves. Lots of countries you have two classes of shares. Its par for the course. And you just price it in.

It’s just that it hasn’t happened in the US for a long time?

I think you will wake up one day and see I wish I had voting rights. But you chose to be a part of this game. I am not feeling sorry for the institutional investors in Google who are crying about the fact that Google does things they don’t like. You bought the stock you live with it.

(The interview was originally published in the Daily News and Analysis(DNA) on May 28,2012. http://www.dnaindia.com/money/interview_facebook-is-a-corporate-dictatorship_1694603)

(Interviewer Kaul is a writer and can be reached at [email protected])

Higher Oil Prices or Higher EMIs? Take your pick

Vivek Kaul

The petrol prices were raised by Rs 6.28 per litre yesterday. With taxes the total comes to Rs 7.54 per litre. Let’s try and understand what impact this increase in prices will have.

The primary beneficiary of this increase will be the oil marketing companies like Indian Oil, Bharat Petroleum and Hindustan Petroleum. The companies had been losing Rs 6.28 per litre of petrol they sold. Since December, when prices were last raised the companies had lost $830million in total. With the increase in prices the companies will not lose money when they sell petrol.

The increase in price will have no impact on the fiscal deficit of the government. The fiscal deficit is the difference between what the government spends and what it earns. The government does not subsidize the oil marketing companies for the losses they make on selling petrol.

It subsidizes them for losses made on selling diesel, kerosene and LPG, below cost.

The losses on account of this currently run at Rs 512 crore a day. The loss last year to these companies because of selling diesel, kerosene and LPG below cost was at Rs 138,541crore. They were compensated for this loss by the government. Out of this the government got the oil and gas producing companies like ONGC, Oil India Ltd and GAIL to pick up a tab of Rs 55,000 crore. The remaining Rs 83,000 odd crore came from the coffers of the government.

What is interesting that when the budget was presented in March, the oil subsidy bill for the year 2011-2012 (from April 1, 2011 to March 31,2012) was expected to be at around Rs 68,500 crore. The final number was Rs 14,500 crore higher.

The losses for this financial year (from April 1, 2012 to March 31,2012) are expected to be at Rs Rs. 193,880 crore. If the losses are divided between the government and the oil and gas producing companies in the same ratio as last year, then the government will have to compensate the oil marketing companies with around Rs 1,14,000 crore. The remaining money will come from the oil and gas producing companies.

The trouble is in two fronts. It will pull down the earnings of the oil and gas producing companies. But that’s the smaller problem. The bigger problem is it will push up the fiscal deficit. If we look at the assumptions made in the budget for the current financial year, the oil subsidies have been assumed at Rs Rs 43,580 crore. If the government has to compensate the oil marketing companies to the extent of Rs 1,14,000 crore, it means that the fiscal deficit will be pushed up by around Rs 70,000 crore more (Rs 1,14,000crore minus Rs 43,580 crore), assuming all other expenses remain the same.

A higher fiscal deficit would mean that the government would have to borrow more. A higher government borrowing will ‘crowd-out’ the private borrowing and push interest rates higher. This would mean higher equated monthly installments(EMIs) for people who have loans to pay off or are even thinking of borrowing.

The only way of bringing down the interest rates is to bring down the fiscal deficit. The fiscal deficit target for the financial year 2012-2013 has been set at Rs 5,13,590 crore. The government raises this money from the financial system by issuing bonds which pay interest and mature at various points of time. Of this amount that the government will raise, it will spend Rs 3,19,759 crore to pay interest on the debt that it already has. Rs 1,24,302 crore will be spent to payback the debt that was raised in the previous years and matures during the course of the year 2012-2013. Hence a total of Rs 4,44,061 crore or a whopping 86.5% of the fiscal deficit will be spent in paying interest on and paying off previously issued debt. This is an expenditure that cannot be done away with.

The other major expenditure for the government during the course of the year are subsidies. The total cost of subsidies during the course of this year has been estimated to be at Rs Rs 1,90,015 crore. The subsidies are basically of three kinds: oil, food and petroleum. The food subsidy is at Rs 75,000 crore. This is a favourite with Sonia Gandhi and hence cannot be lowered. And more than that there is a humanitarian angle to it as well.

The fertizlier subsidies have been estimated at Rs 60,974 crore. This is a political hot potato and any attempts to cut this in the pst have been unsuccessful and have had to be rolled back. There are other subsidies amounting to Rs 10,461 crore which are minuscule in comparison to the numbers we are talking about.

This leaves us with oil subsidies which have been estimated to be at Rs 43,580 crore. This as we see will be overshot by a huge level, if oil prices continue to be current levels. Even if prices fall a little, the subsidy will not come down by much. .

Hence if the government has to even maintain its deficit (forget bringing it down) the only way out currently is to increase the price of diesel, LPG and kerosene. Diesel is a transport fuel and an increase in its price will push prices inflation in the short term. But maintain the fiscal deficit will at least keep interest rates at their current levels and not push them up from their already high levels.

If the government continues to subsidize diesel, LPG and kerosene, interest rates are bound to go up because it will have to borrow more. This will mean higher EMIs for sure. It would also mean businesses postponing expansion because higher interest rates would mean that projects may not be financially viable. It would also mean people borrowing lesser to buy homes, cars and other things, leading to a further slowdown in a lot of sectors. In turn it would mean lower economic growth.

That’s the choice the government has to make. Does it want the citizens of this country to pay higher fuel and gas prices? Or does it want them to pay higher EMIs? There is no way of providing both.

(The article originally appeared at www.rediff.com on May 24,2012. http://www.rediff.com/business/slide-show/slide-show-1-special-higher-oil-prices-or-higher-emis-take-your-pick/20120524.htm)

(Vivek Kaul is a writer and can be reached at [email protected])