Vivek Kaul

Shashi Tharoor before he decided to become a politician was an excellent writer of fiction. It is rather sad that he hasn’t written any fiction since he became a politician. A few lines that he wrote in his book Riot: A Love Story I particularly like. “There is not a thing as the wrong place, or the wrong time. We are where we are at the only time we have. Perhaps it’s where we’re meant to be,” wrote Tharoor.

India’s slowing economic growth is a good case in point of Tharoor’s logic. It is where it is, despite what the politicians who run this country have to say, because that’s where it is meant to be.

The Prime Minister Manmohan Singh in his independence-day speech laid the blame for the slowing economic growth in India on account of problems with the global economy as well as bad monsoons within the country. As he said “You are aware that these days the global economy is passing through a difficult phase. The pace of economic growth has come down in all countries of the world. Our country has also been affected by these adverse external conditions. Also, there have been domestic developments which are hindering our economic growth. Last year our GDP grew by 6.5 percent. This year we hope to do a little better…While doing this, we must also control inflation. This would pose some difficulty because of a bad monsoon this year.”

So basically what Manmohan Singh was saying that I know the economic growth is slowing down, but don’t blame me or my government for it. Singh like most politicians when trying to explain their bad performance has resorted to what psychologists calls the fundamental attribution bias.

As Vivek Dehejia an economics professor at Carleton University in Ottawa, Canada, told me in a recent interview I did for the Daily News and Analysis (DNA) “Fundamentally attribution bias says that we are more likely to attribute to the other person a subjective basis for their behaviour and tend to neglect the situational factors. Looking at our own actions we look more at the situational factors and less at the idiosyncratic individual subjective factors.”

In simple English what this means is that when we are analyzing the performance of others we tend to look at the mistakes that they made rather than the situational factors. On the flip side when we are trying to explain our bad performance we tend to blame the situational factors more than the mistakes that we might have made.

So in Singh’s case he has blamed the global economy and the deficient monsoon for the slowing economic growth. He also blamed his coalition partners. “As far as creating an environment within the country for rapid economic growth is concerned, I believe that we are not being able to achieve this because of a lack of political consensus on many issues,” Singh said.

Each of these reasons highlighted by Singh is a genuine reason but these are not the only reasons because of which economic growth of India is slowing down. A major reason for the slowing down of economic growth is the high interest rates and high inflation that prevails. With interest rates being high it doesn’t make sense for businesses to borrow and expand. It also doesn’t make sense for you and me to take loans and buy homes, cars, motorcycles and other consumer durables.

The question that arises here is that why are banks charging high interest rates on their loans? The primary reason is that they are paying high interest rate on their deposits.

And why are they paying a high interest rate on their deposits? The answer lies in the fact that banks have been giving out more loans than raising deposits. Between December 30, 2011 and July 27, 2012, a period of nearly seven months, banks have given loans worth Rs 4,16,050 crore. During the same period the banks were able to raise deposits worth Rs 3,24,080 crore. This means an incremental credit deposit ratio of a whopping 128.4% i.e. for every Rs 100 raised as deposits, the banks have given out loans of Rs 128.4.

Thus banks have not been able to raise as much deposits as they are giving out loans. The loans are thus being financed out of deposits raised in the past. What this also means is that there is a scarcity of money that can be raised as deposits and hence banks have had to offer higher interest rates than normal to raise this money.

So the question that crops up next is that why there is a scarcity of money that can be raised as deposits? This as I have said more than few times in the past is because the expenditure of the government is much more than its earnings.

The fiscal deficit of the government or the difference between what it earns and what it spends has been going up, over the last few years. For the financial year 2007-2008 the fiscal deficit stood at Rs 1,26,912 crore. It went up to Rs 5,21,980 crore for financial year 2011-2012. In a time frame of five years the fiscal deficit has shot up by nearly 312%. During the same period the income earned by the government has gone up by only 36% to Rs 7,96,740 crore.

This difference is made up for by borrowing. When the borrowing needs of the government go through the roof it obviously leaves very little on the table for the banks and other private institutions to borrow, which in turn means that they have to offer higher interest rates to raise deposits. Once they offer higher interest rates on deposits, they have to charge higher interest rate on loans.

A higher interest rate scenario slows down economic growth as companies borrow less to expand their businesses and individuals also cut down on their loan financed purchases. This impacts businesses and thus slows down economic growth.

The huge increase in fiscal deficit has primarily happened because of the subsidy on food, fertilizer and petroleum. One of the programmes that benefits from the government subsidy is Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act (MGNREGA). The scheme guarantees 100 days of work to adults in any rural household. While this is a great short term fix it really is not a long term solution. If creating economic growth was as simple as giving away money to people and asking them to dig holes, every country in the world would have practiced it by now.

As Raghuram Rajan, who is taking over as the next Chief Economic Advisor of the government of India, told me in an interview I did for DNA a couple of years back “The National Rural Employment Guarantee Scheme (NREGS, another name for MGNREGA), if appropriately done it is a short term insurance fix and reduces some of the pressure on the system, which is not a bad thing. But if it comes in the way of the creation of long term capabilities, and if we think NREGS is the answer to the problem of rural stagnation, we have a problem. It’s a short term necessity in some areas. But the longer term fix has to be to open up the rural areas, connect them, education, capacity building, that is the key.”

But the Manmohan Singh led United Progressive Alliance seems to be looking at the employment guarantee scheme as a long term solution rather than a short term fix. This has led to burgeoning wage inflation over the last few years in rural areas.

As Ruchir Sharma writes in Breakout Nations – In Pursuit of the Next Economic Miracles “The wages guaranteed by MGNREGA pushed rural wage inflation up to 15 percent in 2011”.

Also as more money in the hands of rural India chases the same number of goods it has led to increased price inflation as well. Consumer price inflation currently remains over 10%. The most recent wholesale price index inflation number fell to 6.87% for the month of July 2012, from 7.25% in June. But this experts believe is a short term phenomenon and inflation is expected to go up again in the months to come.

As Ruchir Sharma wrote in a column that appeared yesterday in The Times of India “For decades India’s place in the rankings of nations by inflation rates also held steady, somewhere between 78 and 98 out of 180. But over the past couple of years India’s inflation rate is so out of whack that its ranking has fallen to 151. No nation has ever managed to sustain rapid growth for several decades in the face of high inflation. It is no coincidence that India is increasingly an outlier on the fiscal front as well with the combined central and state government deficits now running four times higher than the emerging market average of 2%.” (You can read the complete column here).

So to get economic growth back on track India has to control inflation. The Reserve Bank of India (RBI) has been trying to control inflation by keeping the repo rate, or the rate at which it lends to banks, at a high level. One school of thought is that once the RBI starts cutting the repo rate, interest rates will fall and economic growth will bounce back.

That is specious argument at best. Interest rates are not high because RBI has been keeping the repo rate high. The repo rate at best acts as an indicator. Even if the RBI were to cut the repo rate the question is will it translate into interest rate on loans being cut by banks? I don’t see that happening unless the government clamps down on its borrowing. And that will only happen if it’s able to control the subsidies.

The fiscal deficit for the current financial year 2012-2013 has been estimated at Rs Rs Rs 5,13,590 crore. I wouldn’t be surprised if the number even touches Rs 600,000 crore. The oil subsidy for the year was set at Rs 43,580 crore. This has already been exhausted. Oil prices are on their way up and brent crude as I write this is around $115 per barrel. The government continues to force the oil marketing companies to sell diesel, LPG and kerosene at a loss. The diesel subsidy is likely to continue given that with the bad monsoon farmers are now likely to use diesel generators to pump water to irrigate their fields. With food inflation remaining high the food subsidy is also likely to go up.

The heart of India’s problem is the huge fiscal deficit of the government and its inability to control it. As Sharma points out in Breakout Nations “It was easy enough for India to increase spending in the midst of a global boom, but the spending has continued to rise in the post-crisis period…If the government continues down this path India, may meet the same fate as Brazil in the late 1970s, when excessive government spending set off hyperinflation and crowded out private investment, ending the country’s economic boom.”

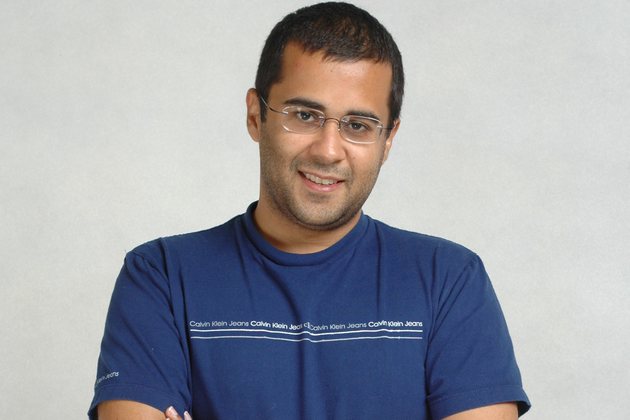

These details Manmohan Singh couldn’t have mentioned in his speech. But he tried to project a positive picture by talking about the planning commission laying down measures to ensure a 9% rate of growth. The one measure that the government needs to start with is to cut down the fiscal deficit. And the probability of that happening is as much as my writing having more readers than that of Chetan Bhagat. Hence India’s economic growth is at a level where it is meant to be irrespective for all the explanations that Manmohan Singh gave us and the hope he tried to project in his independence-day speech.

But then you can’t stop people from dreaming in broad daylight. Even Manmohan Singh! As the great Mirza Ghalib who had a couplet for almost every situation in life once said “hui muddat ke ghalib mar gaya par yaad aata hai wo har ek baat par kehna ke yun hota to kya hota?”

(The article originally appeared on www.firstpost.com on August 16,2012. http://www.firstpost.com/economy/of-9-economic-growth-and-manmohans-pipedreams-419371.html)

Vivek Kaul is a writer and can be reached at [email protected]

Will Ramdev succeed in politics? History isn’t on his side

Vivek Kaul

Some two and a half years back I had told an aunt of mine that Baba Ramdev was getting ready to enter politics. My aunt, who recently retired after nearly four decades of teaching in the Kendriya Vidyalaya system of schools, wouldn’t agree with me. “He just wants us to be healthy,” was her reply.

I had been following Baba Ramdev’s early morning yoga classes on television regularly for almost six months in a bid to control my ever expanding waistline. The aasanas that Baba showed over that period remained more or less the same. But the commentary that accompanied those aasanas had gradually become more and more political.

In that context, I am not surprised at Baba’s decision to take the Congress party led United Progressive Alliance (UPA) Government head on and ask his supporters not to vote for the Congress in the coming elections.

Baba Ramdev may not form his own party in the days to come. He may not even contest any elections but by asking people not to vote for the Congress he has more or less signaled his entry into politics.

So the question that arises now is that will he succeed at what he is trying to do or will he just be a flash in the pan and disappear from the limelight in a couple of years?

Babas and religious gurus have always been an essential part of the Indian political system. Dhirendra Bramhachari was known to be close to Indira Gandhi. Chandraswami was known to be close to PV Narsimha Rao.

Long time Gandhi family loyalist Arjun Singh was known to be close to the Mauni Baba of Ujjain. Mauni Baba even took credit for Arjun Singh surviving a massive heart attack in 1989.

As Rashid Kidwai writes in 24 Akbar Road – A Short History Behind the Fall and the Rise of the Congress “The doctors at Hamidia Hospital in Bhopal had almost given up on him( Arjun Singh) when a call from Rajiv Gandhi ensured a timely airlift to Delhi’s Escort Heart Institute. His spiritual guru, Mauni Baba of Ujjain, took credit for the miracle. The guru, who had taken a vow of silence, reached Delhi and shut himself off to conduct various yagnas for his health. As Union Communications Minister, Singh had given the guru two telephone connections. The act promoted a Hindi daily to run the headline, ‘Jab Baba bolte nahin, to do telephone kyun?’

Like Singh, the various politicians took care of their respective gurus. Indira Gandhi ensured that Dhirendra Bramhachari had a weekly show on Doordarshan to promote the benefits of yoga. Several politicians were known to be close to the Satya Sai Baba as well. His trust being a publically charitable trust did not pay any income tax.

So babas and religious gurus have always been close to Indian politicians and politics. They have been the backroom boys who have rarely come out in the open to take on the government of the day head on.

But there are always exceptions that prove the rule. One such person who did this rather successfully for a brief period was Sadhvi Rithambara. Her fiery speeches in the early 1990s were very fairly popular across the length and breadth of North India and Bihar. I remember listening to one of her banned tapes before the demolition of the Babri Masjid. It was full of expletives and exhorted the cause of a Ram Mandir being built at the site of the Babri Masjid in Ayodhya.

As Haima Deshpande writes in the latest edition of the Open “By the early 1990s, the Sadhvi was scandalising secular India with her rabble-rousing along a campaign trail to replace Ayodhya’s Babri Masjid with a Ram Mandir. At first, her anti-Muslim tirades were full of expletives, exhorting Hindus to reclaim what she said was rightfully theirs. After a brush with the law, she toned herself down, but her message was roughly the same. While the entry of Parsis to India was like sugar sweetening milk, she would say, that of Muslims was like lemon curdling the country (delivered with a certain inflexion in Hindi, that verb could sound rather crude).” The Sadhvi is now known as Didi Maa and runs a home for destitute women and abandoned children which was set up in 2002, Deshpande points out.

What these examples tell us is that Babas and religious gurus have never operated in the openly in the open sesame of Indian politics. And when they have they have not survived for a very long period of time.

At a broader level people who have been successful in other walks of life have rarely been able to transform themselves into career politicians. When these people have tried to enter politics they have either been unsuccessful or have retreated back very quickly.

Let’s take the case of Russi Modi, the man who once played the piano along with Albert Einstein, when the great physicist was playing the violin. Modi was the Chairman and Managing Director of the Jamshedpur based Tata Iron and Steel Company (TISCO, now known as Tata Steel). After retiring from TISCO, Modi fought the Lok Sabha elections from Jamshedpur and lost.

Amitabh Bachchan won the Lok Sabha elections from Allahabad in 1984 defeating H N Bahuguna. He resigned three years later. Dev Anand unsuccessfully tried to form a political party in the late 1980s. Rajesh Khanna and Dharmendra were also a one term Lok Sabha members. Hema Malini has achieved some success in politics but she is used more by the BJP to attract crowds rather than practice serious politics. The same stands true for Smriti Irani of the Kyunki Saas Bhi Kabhi Bahu Thi fame.

Deepika Chikalia, the actress who played the role of Sita in Ramanand Sagar’s Ramayana, was a one time member of Lok Sabha from Baroda. So was Nitish Bhardwaj who played Krishna in BR Chopra’s Mahabharat, from Jamshedpur.

The only state where film celebrities have successfully made it into politics and remained there is Tamil Nadu. Andhra Pradesh has the isolated example of NT Rama Rao who was successful at politics as well as being the biggest superstar of Telgu cinema. But more recently when the reigning superstar of Telgu cinema, Chiranjeevi, tried to follow NTR, he was unsuccessful. He had to finally merge his Praja Rajyam party rather ironically with the Congress.

Imran Khan Niazi, the biggest sports icon that our next door neighbour Pakistan ever produced formed the Tehreek-e-Insaf party in 1996. When Imran Khan started making speeches before the 1997 elections, his rallies got huge crowds. But the party failed to win a single seat in the election, despite the fact that Imran Khan contested from nine different seats. He lost in each one of them. But to Khan’s credit he still hasn’t given up.In India cricketers like Manoj Prabhakar and Chetan Sharma have unsuccessfully tried to contest elections.

The broader point is that people from other walks of life haven’t been able to successfully enter politics if we leave out the odd filmstar. There are several reasons for the same. Their expertise does not lie in politics and lies somewhere else, something Amitabh Bachchan found out very quickly. Politics also requires a lot of patience and money. This is something that everybody doesn’t have.

Also some of these successful people come with stories attached with them. Ramdev’s story was “practicing yoga can cure any disease”. Those who have seen his yoga DVDs will recall the line “Karte raho, cancer ka rog bhi theek hoga“. This story helped him build a huge yoga empire with an annual turnover of over Rs 1000 crore. The story was working well, until Ramdev decided to diversify, and enter politics.

As marketing guru Seth Godin writes in All Marketers Are Liars: “Great stories happen fast. They engage the consumer the moment the story clicks into place. First impressions are more powerful than we give them credit for.”

So Ramdev’s success now clearly depends on the perception that he is able to form in the minds of the people of this country. Will they continue to look at him as a yoga guru who is just dabbling in some politics? Or will they look at him as a serious politician whose views deserve to be heard and acted on? Also will Baba Ramdev want to continue investing time and energy in the hurly-burly world of politics? That time will tell.

But what about the all the people that Baba Ramdev has been able to attract, you might ask me? Crowds as Imran Khan found out are not always a reflection of whether an individual will be successful in politics. And history clearly is not on Ramdev’s side.

(The article originally appeared on www.firstpost.com on August 15,2012. http://www.firstpost.com/india/will-ramdev-succeed-in-politics-history-isnt-on-his-side-418952.html)

(Vivek Kaul is a writer and can be reached at [email protected] )

Why Chetan Bhagat sells, despite the mediocrity tag

Vivek Kaul

It was sometime in late 2005 or early 2006 my memory fails me, when I ran into Chetan Bhagat at the Crossword book store at Juhu in Mumbai. Those were the days when he was still an investment banker based out of Hong Kong. He was passing by the book store and had decided to drop in to check how his second book was selling.

One Night At the Call Centre had just come out and was number one on the bestsellers list. He hadn’t become a celebrity as he is now and people took some time to recognize him. He sat down and started signing books that fans brought to him.

I must confess that I was a fan of his writing back then and had loved reading Five Point Someone (On a totally different note I was even a fan of Himesh Reshammiya for a brief period). So I promptly bought his two books and got them autographed from him.

Bhagat’s first book Five Point Someone wasn’t a literary phenomenon but had broken all sales records. The story was set in IIT Delhi and had a certain charm to it. Bhagat must have borrowed a lot from his own life and that honesty reflected in the book.

But Bhagat had had a tough time finding a publisher for his first book. Bhagat had to do the rounds of several publishers before Rupa latched onto Five Point Someone. As one of the editors who had rejected his manuscript wrote in the Open magazine “He later went to a rival firm and became a publishing sensation overnight, and to this day, our boss complains bitterly that he missed out on the biggest bestseller of the decade because he went by the judgement of three Bengali women—a flawed demographic, if there ever was one!” (You can read the complete piece here).

In the CD that accompanied the manuscript of Five Point Someone Bhagat had also elaborated on a marketing plan. The M word did not go down well with the female Bengali editor and as she remarked in the Open “A marketing strategy that would ensure the book became an instant bestseller…If only he had written his manuscript with half the dedication he had put into his marketing plan! “

Hence, the so called “sophisticated” people at the biggest Indian publishing houses missed out on India’s bestselling English author primarily because his writing wasn’t literary enough. ,Bhagat eventually did find a publisher and the rest as they say is history.

The day I ran into Bhagat was a Sunday and I came back home and finished reading One Night At a Call Centre in a few hours. I found the book pretty boring and at the same time got a feeling that the author had decided to put together a quickie to cash in on the success of his first book. But then I was probably in a minority who thought that way. The book became an even bigger success than Five Point Someone. His next book was The Three Mistakes of My Life. I couldn’t read the book beyond the first twenty pages. His next two books, Two States and Revolution 2020, I haven’t attempted to read till date.

Very recently his sixth book and his first work of non-fiction What Young India Wants has come out. The book is essentially a collection of his newspaper columns. It is also an extension of his attempts over the last few years at building a more serious image for himself of someone who not only writes popular books but also understands the pulse and paradoxes of Young India.

As the Open magazine puts it “Years spent as a pariah in literary circles seem to have caught up with Chetan Bhagat, India’s largest-selling fiction writer. He’s excited that he’s moved on to some “meaningful” writing as well. “The charge against me is I’m too flippant,” he says. The author, who sees himself as a spokesperson for India’s youth, has just launched his latest book, What Young India Wants, a compilation of his essays on issues troubling the country, mainly corruption and discrimination based on caste and religion. He’s hoping that it will gain him some credibility as a writer.”

So what does Bhagat come up in his tour de force? Here are some samples.

On Pakistan:

“More than anything else, we want to teach Pakistan a lesson. We want to put them in their place. Bashing Pakistan is considered patriotic. It also makes for great politics.”

On Voting:

“We have to consider only one criterion—is he or she a good person?”

On Defence:

Money spent on bullets doesn’t give returns, money spent on better infrastructure does…In this technology-driven age, do you really think America doesn’t have the information or capability to launch an attack against India? But they don’t want to attack us. They have much to gain from our potential market for American products and cheap outsourcing. Well let’s outsource some of our defence to them, make them feel secure and save money for us. Having a rich, strong friend rarely hurt anyone

On Women: (Rajyasree Sen hope you are reading this):

“There would be body odour, socks on the floor and nothing in the fridge to eat,” writes Bhagat on what would happen if women weren’t around.

On Self Promotion:

“I had for years wanted to create more awareness for a better India. Wasn’t now the time to do it with full gusto?”

The book like other Bhagat books presents a very simplistic vision of the world that we live in and is accompanied by some pretty ordinary writing. “What young India wants is meri naukri and meri chokri,” Bhagat said while promoting the book. Bhagat also comes up with some preposterous solutions like the one where he talks about outsourcing India’s defence needs to America. Really?

At the same time the book stinks of self promotion. In interviews that Bhagat has given after the book came out he continues to refer himself as destiny’s child.

Thus it’s not surprising that Bhagat has come in for a barrage of criticism for his overtly simplistic views and his unabashed attempts at promoting himself. “Bhagat is not a thinker. He is our great ‘unthinker’, as sure a representative of heedless ‘new India’ as the khadi-clad politician is of old India,” wrote Shougat Dasgupta in Tehalka. (You can read the complete piece here).

The criticism notwithstanding Bhagat’s books sell like hot cakes. “His publishers, Rupa & Co., are counting on it. Rupa, which has brought out all of Bhagat’s novels since Five Point Someone in 2004, says that 500,000 copies of an initial print run of 575,000 were sold to retailers in a day, and booksellers have already begun to place repeat orders,” reports the Mint.

Given that there must be something right about them. The answer lies in the fact that the mass market is not intellectual. It’s mediocre. It would rather prefer the movies of Salman Khan than an Anurag Kashyap. It would rather go and watch a mindless Rowdy Rathore rather than a Gangs of Wasseypur, which demands attention from the viewer. It would rather watch a Kyunki Saans Bhi Kabhi Bahu Thi than the History channel.

The mass market likes stuff which is not too heavy. Chetan Bhagat fulfills that need. There has always been space for the kind of mindless and simple stuff that Bhagat writes. How else do you explain the success of the Mills & Boons series? Also in a country like India where people are just about starting to learn English, it’s easier for them to understand a Chetan Bhagat than a Salman Rushdie or even a much easier Jeffrey Archer for that matter.

Bhagat’s writing is thus initiating people into reading. And in that sense it’s a good thing. Let me give a personal example to elaborate on this. Recently I started listening to Hindustani Classical music, more than 25 years after I first started listening to music. My taste has evolved the years. I started with the trashy Hindi film music of the 1980s, moved onto the Hindi film music of the fifties and the sixties, then went into Ghazals (which had its own cycle. First Jagjit Singh, then came Ghulam Ali, then Mehdi Hasan and finally came the likes of Begum Akhtar) and so on. It took me almost 25 years to start listening to Hindustani classical music. Maybe I was slower than the usual. But the point is that nobody starts of listening to Hindustani classical music from day one. We have to go through our share of “crappy” music to arrive at that. If I hadn’t heard the crappy music of the 1980s, I wouldn’t be listening to Ustad Bismillah Khan today.

Similarly readers who start reading books with Chetan Bhagat are likely to move onto much better stuff over the years. In that sense Bhagat’s writing is a necessary evil. The entire market for Indian writing in English has expanded since Chetan Bhagat started writing. Before that Indian writing in English did not appeal to the average Indian. Now it does.

It would also help them reach a stage of understanding where they will be able to understand the following paragraph written by Shougat Dasgupta in Tehelka.

“Bhagat is adept at this sort of corporate speak, bland pabulum that appears to be reasonable, but is buzzword piled upon truism piled upon platitude, a tower built on the soft, tremulous sands of cliché. A Bhagat column makes a house of cards seem as substantial as the pyramid at Giza.”

(The article originally appeared on www.firstpost.com on August 14,2012. http://www.firstpost.com/india/why-chetan-bhagat-sells-despite-the-mediocrity-tag-417177.html)

(Vivek Kaul is a writer and can be reached at [email protected])

Why Fareed Zakaria failed, and Salim-Javed got away

Vivek Kaul

“So you must be shocked?” asked a friend on Facebook chat on Saturday.

Now given the times that we live in it took me a while to figure out that she was talking about Fareed Zakaria and not about yet another train accident, riot or a flash flood.

“Nothing is sacrosanct in the media anymore,” was her far reaching conclusion.

For the uninitiated Fareed Zakaria is a former editor of the Newsweek magazine who has recently admitted to plagiarizing a column he wrote advocating gun control in America. He was stupid enough to borrow portions of the column liberally from a column written by Jill Lepore in the New Yorker magazine. (You can read about the entire controversy here). Till recently Zakaria was Editor-at-Large at the Time magazine and also hosted a programme called GPS on CNN.

As I spoke to my friend on Facebook chat there was a qawali playing on my CD player. Sabri Brothers were singing “ajmer ko jaana hai”. It was one of the random CDs that I had picked up around a couple of years back but had never gotten around to listening.

I had heard the tune before. The tune was exactly similar to that of the super-hit song “ek pyar ka nagma hai, maujon ki rawani hai” sung by Mukesh and Lata Mangeskhar, written by Santosh Anand and set to tune by Laxmikant-Pyarelal (LP).

Soon I logged out of Facebook chat and was trying to figure out who copied whom? Typically some Googling always helps in these cases. (The best website to visit in such cases is www.itwofs.com. The website normally has the original song as well as the copied song).

But it did not help in this case. Various questions cropped up in my mind.

Did LP set to tune their song first? Or were Sabri brothers singing what is a traditional tune? Or did they copy LP? Or for that matter did LP copy the Sabri brothers? I don’t know (Maybe the readers can throw some light on this).

No such problems exist in Zakaria’s case though. It’s an open and shut case. He copied from the New Yorker and has admitted to doing the same.

But such clarity is not always there. Let me give an example to explain. A couple of years back I discovered this Jim Reeves song called “My Lips Are Sealed”. As I heard the song over and over again it sounded very similar to a Hindi film song. But I just couldn’t which one.

It took me an entire day to figure out that the song sounded similar to “ajeeb dastan hai ye” from the movie Dil Apna Aur Preet Parai. The song had some beautiful lyrics written by Shailendra and set to tune by Shankar-Jaikishan.

If I were to use the language of the Hindi film industry the song was inspired and not copied. And the interesting part was that Shailendra had written some amazing lyrics to the tune of My Lips Are Sealed. And Lata Mangeshkar had made the song immortal by lending her melodious voice to it. So something good came out of the copying.

Now here are a few lines to ponder over.

‘So, young man. So now you have also starred frequenting these places?’

‘Yes. I often come by to pay Flush,’ Imran said respectfully.

‘Flush! Oh, so now you play Flush…

”Yes, yes. I feel like it when I am a bit drunk…

”Oh! So you have also started drinking?’

‘What can I say? I swear I’ve never drunk alone. Frequently I find hookers who do not agree to anything without a drink…’

If you were starting to wonder whether these lines are from that movie, which they happen to call the biggest Hindi film hit of all time, well you are not totally wrong.

The lines do sound surreptitiously similar to the ‘Veeru Ki Shaadi‘ proposal scene in the biggest Hindi blockbuster of all time Sholay. But these lines are not from Sholay.

Actually, these are lines from a book called The House of Fear written by the grandmaster of Urdu crime fiction Ibn-E-Safi. The book was originally published in Urdu in 1955 as Khaufnak Imarat. It was first in the series of 120 odd books that Safi wrote featuring the quirky detective Ali Imran MSc, PhD.

Ibn-E-Safi was the pen name of Asrar Narvi, who came from the village Nara in the Allahabad district. Born in 1929, his pen name literally means ‘son of Safi’ (his father’s name was Safiullah). Narvi, who moved to Pakistan after partition, was a poet who started writing detective fiction in 1952, with the Jasoosi Duniya series which had Colonel Faridi and Captain Hameed as the main protagonists.

In 1953, Saifi started writing the Imran series in Urdu. The same series of books appeared in Hindi as well with exactly the same story line except for the fact that a character called Vinod replaced Imran.

Sholay was released in 1975, whereas Safi’s Khaufnak Imarat was released two decades earlier in 1955. Given this, Salim Khan and Javed Akhtar (the writers of Sholay) copied (or should we say “were inspired” in the Bollywood sense of the term) the scene which is regarded by many as one of the greatest comic scenes in the history of Hindi cinema, from Ibn-E-Safi.

This is not surprising given that Javed Akhtar in his growing up years is known to have read Ibn-E-Safi. “He had tremendous flair and sophistication…Safi’s novels created an imaginary city that could have been the San Francisco of the 50s in India. His penchant for villains with striking names like Gerald Shastri and Sang Hi taught me the importance of creating larger-than life characters such as Gabbar and Mogambo as a scriptwriter,” Akhtar told the Hindustan Times a couple of years back.

In the book The Making of Sholay, Anupama Chopra, writes about the inspiration behind the scene. “A disgruntled parent also inspired the classic ‘Veeru Ki Shaadi‘ proposal scene. Javed was in love with actress Honey Irani. They had first met on the sets of Seeta aur Geeta and much of their courtship was conducted there. But Mama Perin Irani kept a strict eye on her daughters. And Javed, still a struggling writer, had little to recommend him. He had presented himself but had failed to make an impression at all. Salim was a little senior. He had also worked in Bachpan, which Irani had produced. Naturally, Javed requested his partner to carry the proposal. He didn’t know that partner didn’t approve either.”

What followed was an interaction between Perin Irani and Salim Khan, which went like this:

‘Ladka kaisa hai?’

‘We are partners and I wouldn’t work with anyone unless I approve of him. Lekin daaru bahut peeta hai’

‘Kya? Daaru bahut peeta hai!’

‘Aaj kal bahut nahi peeta, bas ek do peg. Aur ismein aisi koi kharabi nahin hai. Lekin daaru peene ke baad red light area main bhi jaata hai.’

Chopra further writes in her book that the last line of the dialogue in the movie- ‘khandaan ka pata chalet hi aapko khabar kar denge‘ is fiction.

There are a few issues that arise here. The first of course is that Salim-Javed copied a scene without any attribution. But that has always been the norm with the Hindi film industry. The bigger issue of course is that even though the copied the scene they tried to pass it off as an inspiration from real life, which as I have shown above it clearly is not. Unless of course, Salim Khan had also read the book and repeated the lines when he went to meet Javed Akhtar’s would be mother-in-law. But that still doesn’t mean the scene wasn’t copied.

(On a different note, 20 years back I saw Mahesh Bhat’s Dil Hai Ki Maanta Nahi at the Sandhya Cinema in Ranchi and fell in love with the movie and its heroine Pooja Bhat. A few years back I saw It Happened One Night, the Hollywood original. Dil Hai Ki Maanta Nahi other than the songs it has is a scene by scene lift of It Happened One Night, even its dialogues are translated from the English original.)

Getting back to the topic at hand, Fareed Zakaria unlike Salim-Javed, is unlucky to be living in an era where copying something, and passing it off as your own creation, is getting more and more difficult. Zakaria is just finding that out. He has been suspended by both the Time magazine as well as CNN.

In some cases all it takes it is a Google search to figure out whether the article has been copied or not. Even those who copy do not copy from a mainstream magazine like the New Yorker. They are more likely to copy it from some obscure journal or research paper. But even there the chances of getting caught remain pretty high. Also if the original creators find out these days that someone else has copied them they tend to sue for damages.

When Salim-Javed copied times were different. People were not as much aware as they are today and it was easy to pass off someone else’s work as your own. In fact, the writer duo even went to the extent of creating a background for how they had been inspired in writing the “Veeru ki Shaadi” proposal scene. They got away with it. Zakaria clearly didn’t.

To conclude all I can say is that clearly “The Times They Are A Changin!” Now before I get accused of plagiarizing. I didn’t write this. We all know who did.

(The article originally appeared on www.firstpost.com on August 13,2012. http://www.firstpost.com/world/why-fareed-zakaria-failed-and-salim-javed-got-away-416134.html)

(Vivek Kaul is a writer and can be reached at [email protected])

The Armchair Economist talks about seatbelts, popcorn at the movies, why we vote and safe sex

Most economists talk about the graver things in life. Fiscal deficits, interest rates, GDP growth rate and once in a while about why they think that the financial world is coming to an end. But that is not the case with Steven E Landsburg, a Professor of Economics at the University of Rochester in the United States, where students recently elected him Professor of the Year. Nearly twenty years back he wrote The Armchair Economist, a book which brought an easy understanding of the dismal science to the masses. The book has been a bestseller since then motivating him to write a new and revised edition which was published this.

Landsburg is also the author of Fair Play, More Sex is Safer Sex and The Big Questions. He considers himself as the most important figure in the world of modern poetry, in consequence of the his status as the only living being who reads poetry but does not write it. In this freewheeling interview to Vivek Kaul, he talks about why safe belts are unsafe and more sex is safer. He also speaks on why he has no clue of why people vote and popcorns being so expensive at the movies.

Excerpts:

You write that “most of economics can be summarized in four words: people respond to incentives. The rest is commentary.” Why do you say that?

I say that because it’s true, and because it’s important. When the price of lettuce falls, people buy more lettuce. When the price of haircuts falls, people get more haircuts. When the penalty for murder becomes more certain, people commit fewer murders. Due to some combination of arthritis (which makes it difficult for me to turn my head to the right) and irresponsibility, I had a years-long habit of backing the right rear corner of my car into lamp posts, trees and other stationary obstructions. Often enough so the body shop owner joked about giving me a quantity discount. I paid $180 to get my bumper repaired, and I came to think of this as an unavoidable expense. Then in 2002 I got a new car with a fiberglass bumper, backed it into a tree, and discovered that this repair was going to cost me over $500. I have not backed into anything since. Even economists respond to incentives.

Do seatbelts bring down the number of traffic related deaths?

This is a good illustration of why it’s important to think about incentives. A seat belt makes it easier to survive an accident, and so reduces the incentive to avoid accidents in the first place.

But research shows that drivers with seat belts drive less carefully —to such a large extent that they’re just about as likely to die as drivers without seat belts. Also pedestrian deaths seem to have increased. If you find it hard to believe that people drive less carefully when their cars are safer, consider the proposition that people drive more carefully when their cars are more dangerous. This is, of course, just another way of saying the same thing, but somehow people find it easier to believe. If I took the seat belts out of your car, wouldn’t you be more cautious when driving? What if I took the doors off? So if we really wanted to reduce the number of driver deaths, the best policy might be to require every new car to come equipped with a spear, mounted on the steering wheel and pointed directly at the driver’s heart. I predict we’d see a lot less tailgating.

Why is popcorn so expensive at the movies?

Not for any of the reasons that pop quickly into most people’s minds. It’s not enough, for example, to observe that the theater owner is exercising his monopoly power. If that were the whole story, he’d be charging monopoly prices not just for popcorn but for everything else in the theater — the water fountains, the restrooms, and the right to sit down once you’ve entered the theater, for example. The reason he doesn’t charge monopoly prices for those things is that his theater would become less desirable, and to maintain his clientele, he’d have to slash prices at the box office. The same would be true of popcorn, if everyone bought the same amount of popcorn. What’s gained at the popcorn stand is lost at the box office. In fact, it would be even worse than that: By jacking up the price of popcorn, he makes the entire theater experience less desirable, so the total amount he can extract from his customers is lowered, not raised. So the high price of popcorn can’t be explained as a way to exploit customers generally; it must be a way to exploit popcorn-lovers in particular. And this makes sense only if the theater owner believes that popcorn-lovers are more likely to tolerate high prices than popcorn-haters are. Why should that be the case? I’m honestly not sure.

Why is more sex safer sex?

In economics, we’re always thinking about the incentives faced by decision-makers. A decision-maker who does not face all the consequences of his actions often makes bad decisions from a social point of view. For example, the factory owner who decides to pollute the air usually does not feel all the consequences to other people’s health, and therefore over-pollutes. Likewise, people who are very likely to be infected with terrible diseases, when they take new sexual partners, are not accounting for all the consequences of their decisions, which means that from a social point of view, they have too many partners. But the flip side of that is that people who are very likely to be *un*infected, because of their cautious past behavior, when they take new sexual partners, make sex (on average) *safer* for the rest of us. If the likely-to-be-infected are like polluters, then the likely-to-be-uninfected are like anti-polluters: People who go out and pick up trash in the parks.

Why do people vote even when they know that there one single vote is unlikely to influence the outcome? Do they do it because they think that in a democracy it’s a good thing to do?

I haven’t the foggiest idea why people vote. But to say that it’s “a good thing to do” is hardly an explanation. There are lots of good things to do. Instead of spending 15 minutes at the voting booth, you could spend 15 minutes picking up trash in the street. If all you’re looking for is “a good thing to do”, it’s still not clear why you’d choose to vote.

Why are failed corporate chieftains often retired by their boards with very high pensions and a lot of other facilities?

Partly so the chieftains won’t be afraid to take risks. We want our corporate executives to take reasonable risks in order to boost profits. Sometimes reasonable risks lead to failures. If every failure meant personal ruin, executives would be far too cautious. When a corporate risk turns out badly, it’s often hard for the stockholders to know whether the executive was foolish or just unlucky. In case he’s proven foolish, they want to fire him. In case he was just unlucky, they want to treat him well, so that future executives will be willing to risk bad luck.

What is common between college education and long useless peacock tails?

They’re both used to show off. And for that reason, they can both be wasteful. Growing a longer tail than your neighbors’, just to outshine him, is, from a social point of view, a waste of effort — you gain status but your neighbors lose status, so on average nobody comes out ahead. Likewise, getting more years of schooling than your neighbors, insofar as you’re doing it just to advertise your willingness to endure the ordeal, can be socially wasteful. Of course, some students actually learn something useful while they’re in school, so the analogy with the peacock’s tail is incomplete.

Do death penalties deter crime or are there better ways out?

The bulk of the evidence is that passing a death penalty law has very little effect on crime, but that actually executing people has a very substantial effect. In the United States, quite a few studies have found that each execution prevents several murders — typically the studies find that “several” means approximately eight. Of course that doesn’t prove that the death penalty is a wise policy — you might worry, for example, that a government empowered to exact the death penalty will not always use that penalty wisely or even honestly.

An increasing amount government debt puts more money into people’s pockets. What is the logic behind saying that?

There are two ways the government can increase its debt. One is by spending more; the other is by taxing less. Obviously, when they tax less, they put more money into people’s pockets. In that case, the net effect on individual finances is mixed: On the one hand, you, as an individual taxpayer, will eventually be taxed to pay off not just the government’s debt, but also the interest on that debt. On the other hand, you, as an individual taxpayer, not only have more money in your pocket, but also the opportunity to earn interest on that money. Those effects roughly balance out. So if government debt is causing you harm, it must be for reasons more subtle than the ones we usually hear about.

Why do celebrity endorsements increase the sales of the product even when we know that the celebrity has been paid to recommend the product and isn’t really an expert on that product?

The company that hires a celebrity endorser is sinking a lot of money into advertising — money that will take them years to earn back. You can be pretty sure this is a company that cares about its reputation, and so is likely to provide a quality product.

You write that advocates of mandatory helmet laws for motorcycles argue that arider without a helmet raises everyones insurance premiums. The opposite might very well be true. Why do you say that?

If helmets are voluntary, then helmet-wearers get better insurance rates for two reasons. First, helmets prevent injuries. Second, by wearing a helmet you can advertise that you’re a generally cautious person — the sort who probably gets his brakes checked regularly and so on. If helmets become mandatory, you still get the first break — the helmet is just as effective when it’s mandatory. But you no longer have an opportunity to earn the second break, so your premiums might well rise.

Why are employees better off with some amount of monitoring from their employers?

If your employer had no way of knowing whether you were showing up for work or performing any of your duties, it’s unlikely he’d be willing to pay you very much. The more he can verify, the more valuable you’re likely to be. So, for example, software programs that keep track of office workers’ keystrokes, while they might feel intrusive to the worker, are also making that worker more valuable and quite likely account for the employer’s willingness to pay the worker’s salary.

Why does the business world reward good dressers?

I don’t know for sure, but I suspect that the ability to dress well is a signal of several valuable skills: The ability to observe fashion trends, the intuition to understand the limits of what’s acceptable, and the talent to be creative within those well-defined limits.

What made you write the book The Armchair Economist?

One day in 1991, I walked into a medium sized bookstore and counted over 80 titles on quantum physics and the history of the Universe. A few shelves over I found Richard Dawkins’s bestseller *The Selfish Gene* along with dozens of others explaining Darwinan evolution and the genetic code. In the best of these books, I discovered natural wonders, confronted mysteries, learned new ways of thinking, and felt I had shared in a great intellectual adventure,

founded on ideas that are dazzling in their scope and their simplicity. Economics, too, is a great intellectual adventure, but I could find, in 1991, not a single book that proposed to share that adventure with the general public. There was nothing that revealed the economist’s unique way of thinking, using a few simple ideas to illuminate the whole range of human behavior,shake up our preconceptions, and jolt us into new ways of seeing the world.

I resolved to write that book. *The Armchair Economist* was published in 1993, and attracted a large and devoted following. In the intervening 20 years, it has earned much high praise. But what I take most pride in is that *The Armchair Economist* is still widely recognized among economists as the book to give your mother when she wants to understand what you do all day. After 20 years of correspondence with readers, I found new ways of explaining this material that I thought were even clearer and more engaging than in the original book. That — plus my desire to update many of the examples for the 21st century — motivated me to write the new and revised edition that was published in 2012.

(The interview originally appeared in the Daily News and Analysis on August 13,2012. http://www.dnaindia.com/money/interview_the-more-your-employer-snoops-the-more-valuable-you-re-likely-to-be_1727258)

(Interviewer Kaul is a writer and can be reached at [email protected])