Vivek Kaul

So all’s well that ends well. Fareed Zakaria is back in business. But the question that remains is what is plagiarism and what is not? Where does inspiration end and plagiarism start? Let’s explore these questions in the context of music and films, both international as well as Indian, and journalism.

As I write this I am listening to the song “Papa Kehte Hain Bada Naam Karega,” from the movie Qayamat Se Qayamat Tak. The song starts of sounding very similar to an old Roy Orbison song “O Beautiful Lana” but changes track after that and acquires an identity of its own.

The composers Anand-Milind may have clearly been inspired by Roy Orbison in the way they composed the song, but they hadn’t plagiarized.

The bestselling author Malcolm Gladwell in an essay titled Something Borrowed – Should a Charge of Plagiarism Ruin Your Life? tries to examine the questions I raised at the beginning of this piece. He describes an experience that he had with a musically inclined friend of this.

As Gladwell writes “He played Led Zeppelin’s “Whotta Lotta Love” and then Muddy Water’s “You Need Love,” to show the extent to which Led Zeppelin had mined the blues for inspiration…He played “Last Christmas” by Wham! followed by Barry Manilow’s “Can’t Smile Without You” to explain why Manilow might have been startled when he first heard the song.” (You can listen to Can’t Smile Without You here and Last Christmas here)

Gladwell talks about the famous heavy metal band Nirvana and their inspiration. ““That sound you hear in Nirvana,” my friend said at one point, “that soft and then loud kind of exploding thing, a lot of that was inspired by the Pixies. Yet Kurt Cobain” –Nirvana’s lead singer and songwriter – “was such a genius that he managed to make its own. And “Smells Like Teen Spirit’?” – here he was referring to perhaps the best-known Nirvana song. “That’s Boston’s ‘More Than a Feeling.’” He began to hum the riff of the Boston hit, and said, “The first time I heard ‘Teen Spirit,’ I said, ‘That guitar lick is from “More Than a Feeling.”’ But it was different – it was urgent and brilliant and new.”

So what this tells us is that a lot of good old music formed the base of a lot of good new music. But does that imply plagiarism? Clearly not!

Let us look at some examples from closer to home. Talat Mehmood once sang a song “Hain sab se madhur geet wohi jo hum dard ke suron main gaate hain.” This song from the movie Patita was written by Shailendra and set to tune by Shankar Jaikishan. Those who know their English poetry well, will know, that this song is clearly inspired from P B Shelley’s poem To a Skylark, in which he wrote “Our sweetest songs are those that tell of saddest thought.”

Or take the case of the song “Jab hum honge 60 saal ke aur tum hoge 55 ke,bolo preet nibhaogee na phir bhi apne bachpan ki” from Randhir Kapoor’s directorial debut Kal, Aaj aur Kal. Any guesses on what is the inspiration for this song? It is the Beatles number “Will you still need me, will you still feed me, when I am 64?”

In both these cases something new was created from something that was already in existence. Anirudha Bhattacharjee and Balaji Vittal explore the difference between inspiration and plagiarism in their brilliant book R.D.Burman – The Man, The Music. As they write “The pièce de résistance of Shaan was the title song, ‘Pyar karne waale pyar karte hain shaan se,’…The recurring beat in the song could have been inspired, in part, from ‘I feel love’ by Donna Summers, but the song in itself was multidimensional, a grand mix of Asha’s voice and a host of instruments, and bore no resemblance to the Donna Summer hit.” (You can listen to I feel love here).

RD Burman was accused of plagiarising right through his career. “Right through his career, this was probably one question that Pancham had to defend himself against, in most of his interviews, and he often clarified that inspiration was part of the game in any field of art and that his rule was to use one line and recreate an entire song out of the same, something that most composers did,” write Bhattacharjee and Vittal. “Pancham’s stand against charges of plagiarism was matter-of-fact; he did not go out to copy tunes if given the chance to operate on his own terms. He might have needed a start, only to help him trudge along,” the authors add.

There was a lot of inspiration that went into the composition of 1942-A Love Story, RD Burman’s swansong. “With ‘Ek ladki ko dekha’, he got on to the full-on mukhra-antara style that his father once pioneered in ‘Borne gondhe chhonde geetitey’ (the original tune for ‘Phoolon ke rang se’ in Dev Anand’s Prem Pujari), where the mukhra and the antara are merged as one… ‘Kuch na kaho’ found Pancham fleetingly referencing the tune of SD’s ‘Rongila rongila’ (SD as in SD Burman, RD’s father) and giving it a totally different colour and contour, with an orchestration bordering on the symphonic…RD went back to Indian classical music and Rabindranath Tagore for ‘Dil ne kaha chupke se’, basing it on the dual inspiration of Raga Desh and Tagore’s ‘Esho shyama sundaro’, and using strains from ‘Panna ki tamanna‘ (Heera Panna) and ‘Aisa kyon hota hai’ (Ameer Aadmi Garib Aadmi,1985),” the authors point out.

So clearly even the best musicians are inspired when they do their best work. The same stands true for cinema as well. Take the case of “Manorama Six Feet Under.” I saw the movie when it was released and was impressed. The screenplay, dialogues, music, performances…everything about the movie was brilliant. Then I read in a review that the movie was copied from Roman Polanski’s 1974 Jack Nicholson starrer Chinatown.

I managed to locate a VCD of the movie sometime later and happened to see it. Broadly speaking, yes Manorama is a copy of Chinatown. The story is more or less the same. But Navdeep Singh the director of the movie has managed to Indianise it very well. And Manorma‘s end is brilliant, much better than Chinatown‘s vague arty ending. Of course, Manorma does not have the incest angle to the story that Chinatown had.

Now this was a clear case of a director who was inspired. Yes he copied, but I don’t think he plagiarised.

So the distinction between plagiarism and inspiration is not always easy to draw. Malcolm Gladwell makes the point when he writes about something that most journalists have to do at some point of time. As he writes “When I worked at a newspaper, we were routinely dispatched to “match” a story from the Times (I presume Gladwell means the New York Times here): to do a new version of someone else’s idea. But had we “matched” any of the Times’ words – even the most banal of phrases – it could have been a firing offence. The ethics of plagiarism have turned into the narcissism of small differences: because journalism cannot own up to its heavily derivative nature, it must enforce originality only on the level of sentence.”

This is a very important point that Gladwell makes furthering the point that in many cases it is difficult to distinguish what is plagiarism and what is not.

But that is not always the case. Musicians like Bappi Lahiri and Annu Mallik made a career out of plagiarising western tunes. So did Anand-Milind by copying Ilaiyaraaja. The same is true about Sanjay Gupta’s Kaante. It is a shameless copy of Quentin Tarantino’s Reservoir Dogs. In fact Anurag Kashyap, the dialogue writer for the film even admitted in an interview that he was given the DVD of Reservoir Dogs and asked to translate the dialogues. So much for being creative. Sanjay Gupta’s Zinda is also a scene by scene lift of the Korean Movie Old Boy even though Gupta claimed that “international films” inspired him.

So that brings me back to the question that I have been trying to answer “Where does inspiration end and plagiarism start?” The answer to this most likely is: It is a very individual thing. Every creative individual knows where inspiration ends and plagiarism starts. As Justice Potter Stewart, a US judge, wrote in Jacobellis versus Ohio (1964), “I cannot define pornography, but I know it when I see it.”

It’s the same with plagiarism.

The article originally appeared on www.firstpost.com on August 29,2012. http://www.firstpost.com/living/where-does-inspiration-end-and-plagiarism-begin-435291.html

Vivek Kaul is a writer and can be reached at [email protected]

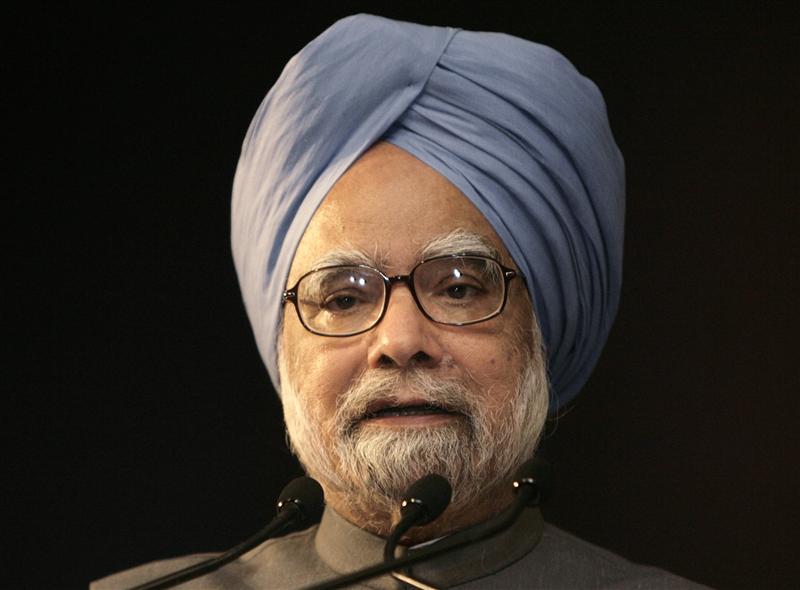

Why Manmohan Singh was better off being silent

Vivek Kaul

So the Prime Minister (PM) Manmohan Singh has finally spoken. But there are multiple reasons why his defence of the free allocation of coal blocks to the private sector and public sector companies is rather weak.

“The policy of allocation of coal blocks to private parties…was not a new policy introduced by the UPA (United Progressive Alliance). The policy has existed since 1993,” the PM said in a statement to the Parliament yesterday.

But what the statement does not tell us is that of the 192 coal blocks allocated between 1993 and 2009, only 39 blocks were allocated to private and public sector companies between 1993 and 2003.

The remaining 153 blocks or around 80% of the blocks were allocated between 2004 and 2009. Manmohan Singh has been PM since May 22, 2004. What makes things even more interesting is the fact that 128 coal blocks were given away between 2006 and 2009. Manmohan Singh was the coal minister for most of this period.

Hence, the defence of Manmohan Singh that they were following only past policy falls flat. Given this, giving away coal blocks for free is clearly UPA policy. Also, we need to remember that even in 1993, when the policy was first initiated a Congress party led government was in power.

The PM further says that “According to the assumptions and computations made by the CAG, there is a financial gain of about Rs. 1.86 lakh crore to private parties. The observations of the CAG are clearly disputable.”

What is interesting is that in its draft report which was leaked earlier in March this year, the Comptroler and Auditor General(CAG) of India had put the losses due to the free giveaway of coal blocks at Rs 10,67,000 crore, which was equal to around 81% of the expenditure of the government of India in 2011-2012.

Since then the number has been revised to a much lower Rs 1,86,000 crore. The CAG has arrived at this number using certain assumptions.

The CAG did not consider the coal blocks given to public sector companies while calculating losses. The transaction of handing over a coal block was between two arms of the government. The ministry of coal and a government owned public sector company (like NTPC). In the past when such transactions have happened revenue from such transactions have been recognized.

A very good example is when the government forces the Life Insurance Corporation (LIC) of India to forcefully buy shares of public sector companies to meet its disinvestment target. One arm of the government (LIC) is buying shares of another arm of the government (for eg: ONGC). And the money received by the government is recognized as revenue in the annual financial statement.

So when revenues from such transactions are recognized so should losses. Hence, the entire idea of the CAG not taking losses on account of coal blocks given to pubic sector companies does not make sense. If they had recognized these losses as well, losses would have been greater than Rs 1.86lakh crore. So this is one assumption that works in favour of the government. The losses on account of underground mines were also not taken into account.

The coal that is available in a block is referred to as geological reserve. But the entire coal cannot be mined due to various reasons including those of safety. The part that can be mined is referred to as extractable reserve. The extractable reserves of these blocks (after ignoring the public sector companies and the underground mines) came to around 6282.5 million tonnes. The average benefit per tonne was estimated to be at Rs 295.41.

As Abhishek Tyagi and Rajesh Panjwani of CLSA write in a report dated August 21, 2012,”The average benefit per tonne has been arrived at by first, taking the difference between the average sale price (Rs1028.42) per tonne for all grades of CIL(Coal India Ltd) coal for 2010-11 and the average cost of production (Rs583.01) per tonne for all grades of CIL coal for 2010-11. Secondly, as advised by the Ministry of Coal vide letter dated 15 March 2012 a further allowance of Rs150 per tonne has been made for financing cost. Accordingly the average benefit of Rs295.41 per tonne has been applied to the extractable reserve of 6282.5 million tonne calculated as above.”

Using this is a very conservative method CAG arrived at the loss figure of Rs 1,85,591.33 crore (Rs 295.41 x 6282.5million tonnes).

Manmohan Singh in his statement has contested this. In his statement the PM said “Firstly, computation of extractable reserves based on averages would not be correct. Secondly, the cost of production of coal varies significantly from mine to mine even for CIL due to varying geo-mining conditions, method of extraction, surface features, number of settlements, availability of infrastructure etc.”

As the conditions vary the profit per tonne of coal varies. To take this into account the CAG has calculated the average benefit per tonne and that takes into account the different conditions that the PM is referring to. So his two statements in a way contradict each other. Averages will have been to be taken into consideration to account for varying conditions. And that’s what the CAG has done.

The PM’s statement further says “Thirdly, CIL has been generally mining coal in areas with

better infrastructure and more favourable mining conditions, whereas the coal blocks offered for captive mining are generally located in areas with more difficult geological conditions.”

Let’s try and understand why this statement also does not make much sense. As The Economic Times recently reported, in November 2008, the Madhya Pradesh State Mining Corporation (MPSMC) auctioned six mines. In this auction the winning bids ranged from a royalty of Rs 700-2100 per tonne.

In comparison the CAG has estimated a profit of only Rs 295.41 per tonne from the coal blocks it has considered to calculate the loss figure. Also the mines auctioned in Madhya Pradesh were underground mines and the extraction cost in these mines is greater than open cast mines. The profit of Rs 295.41was arrived at by the CAG by considering only open cast mines were costs of extraction are lower than that of underground mines.

The fourth point that the PM’s statement makes is that “Fourthly, a part of the gains would in any case get appropriated by the government through taxation and under the MMDR Bill, presently being considered by the parliament, 26% of the profits earned on coal mining operations would have to be made available for local area development.”

Fair point. But this will happen only as and when the bill is passed. And CAG needs to work with the laws and regulations currently in place.

A major reason put forward by Manmohan Singh for not putting in place an auction process is that “major coal and lignite bearing states like West Bengal, Chhattisgarh, Jharkhand, Orissa and Rajasthan that were ruled by opposition parties, were strongly opposed to a switch over to the process of competitive bidding as they felt that it would increase the cost of coal, adversely impact value addition and development of industries in their areas.”

That still doesn’t explain why the coal blocks should have been given away for free. The only thing that it does explain is that maybe the opposition parties also played a small part in the coal-gate scam.

To conclude Manmohan Singh might have been better off staying quiet. His statement has raised more questions than provided answers. As he said yesterday “Hazaaron jawabon se acchi hai meri khamoshi, na jaane kitne sawaalon ka aabru rakhe”.For once he should have practiced what he preached.

(The article originally appeared in the Daily News and Analysis on August 29,2012. http://www.dnaindia.com/analysis/column_why-manmohan-singh-was-better-off-being-silent_1734007))

(Vivek Kaul is a writer and can be reached at [email protected])

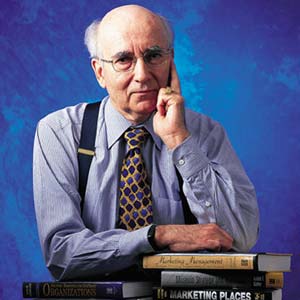

‘The theory of maximizing “shareholder value” has done great harm to businesses’

He is 81 and still going strong. His text book on marketing: Marketing Management is now in its thirteenth edition and still remains an essential read for anyone who hopes to get an MBA degree. He’s often called the father of marketing; something he regards as a compliment, while at the same time ceding the title of the “grandfather of marketing” to management thinker Peter Drucker. Meet Philip Kotler, the S.C. Johnson & Son Distinguished Professor of International Marketing at the Northwestern University Kellogg Graduate School of Management in Chicago. He has been hailed by Management Centre Europe as “the world’s foremost expert on the strategic practice of marketing.” In this freewheeling interview he talks to Vivek Kaul.

Excerpts:

Historically, the vast majority of marketing campaigns have been designed to appeal to our personal needs, lusts, greed or insecurities. To what extent do marketers exploit our human tendencies toward addiction?

Professional marketers see customers as carrying on both mental and emotional processes as they consider purchasing anything. Marketers need to choose the emotional appeal(s) that are relevant to the particular product or service. For a toothpaste, the appeal might be better breath, whiter teeth, or fewer cavities. Or going further, the appeal might be looking sexier, or having longer term dental health. Each competitor must make a choice. In a campaign to get people to stop smoking, one can use a negative appeal (cancer, lung disease, kidney failure) or a positive appeal (better sports performance, living longer for your family). I have advocated using an anti-smoking appeal showing a father who puts out his cigarette when his child comes into view so as not to pass on this bad habit to his children (this is a love appeal). Human emotions range widely and the choice of an appeal is a careful decision that is conditioned by competitors’ appeals and other data. It might seem to the layman that ads often use sex, power, or ego appeals but we could cite many campaigns that use appeals that are less base.

Lately companies have been cutting their marketing budgets, given the troubled times that we are in. Do you think it is a wise move to cut the marketing budget?

That is a panic response and often inappropriate. If competitors decide to cut their marketing budgets, the remaining firm should consider keeping or even increasing its marketing budget. I would go further and sat that a well-heeled firm might even consider buying out some weaker firms during a recession. In normal times, a company finds it hard to move its market share. In recession times, a well-endowed firm can power up its market share. Much depends on the quality of the firm’s products and services. A market leader should consider adding more value rather than cutting its marketing budget. The leader will probably have to alter its messages and media but it doesn’t follow that it needs to cut its marketing budget.

The economist Milton Friedman famously said: “There is one and only one social responsibility of business – to use its resources and engage in activities designed to increase its profits”. What are your thoughts on the social responsibility of marketing?

Milton Friedman was my professor at the University of Chicago and we all admired his brilliance. He was a great believer in leaving businesses unencumbered by regulations and he wanted the leave the business owners to decide what they wanted to do with their profits. I took exception to this view.

Why was that?

Businesses are social organizations that can do great good or great harm. We don’t have to be reminded of the environmental damage companies did by dumping waste into water and pollutants into the air. We don’t have to be reminded of Enron and Madoff and other crooks and pyramid builders. We need appropriate regulations for the competitive system to work. I would argue that companies should go beyond their worship of shareholders who often don’t care about the company and jump in and out of owning its stock. The theory of maximizing “shareholder value” has done great harm to businesses. I have argued that smart companies must focus on the other stakeholders first – customers, employees, suppliers and distributor—and make sure that these stakeholders are all rewarded appropriately and that they work together as a winning team. Satisfying the stakeholders is the best way to maximize the long run profitability of the company. I would propose that as education levels rise in a country, more buyers will expect more from companies and base their brand choices partly on which companies have practiced a caring attitude toward the environment and society. Those companies that operate on the triple bottom line — people, planning and profits – will outperform those who only pursue profit.

A major point in your new book Good Works: ! Marketing and Corporate Initiatives that Build a Better World…and the Bottom Line, is that over the last decade there has been tremendous growth in the number of marketing and corporate initiatives that appeal to our desire to help others or tackle social or environmental problems. Why has this sudden change come about? Can you share some examples with us?

Let’s recognise that societies are facing a growing number of difficult problems – world hunger and poverty, local wars, pollution, environment damage, and faulty education and health systems. Solutions are badly needed. Solutions can only come from the three sectors found in any economy: businesses, NGOs, and government. Today, the governments in most countries are in no condition to solve these problems, given their debt levels and their political impasses. The NGOs have as their purpose to help solve these social problems but are even with less funds available in these recessed times. Business is the only agent of change with the means of doing something to improve the sad state of affairs. The public is increasingly interested in which companies are willing to help make a difference in some of these problems. Consider what Wal-Mart is doing now to reduce air pollution. It is not only ordering the most fuel efficient delivery trucks but now asking its suppliers to change to more efficient trucks or else not be accepted as a supplier. Timberland, the maker of shoes and clothing, does a thorough job of waste reduction and of choosing only suppliers who have good environmental practices. The message is that companies have the capacity to be proactive in making the world a better place for all of us.

What do think are the biggest challenges facing marketing today?

Marketing used to be pretty straight forward. Hire able salespeople and brand managers and a top advertising agency and the team will attract many triers and buyers. Marketers didn’t have much input into the product: their job was to get the product sold. Today the picture is radically different. The social media revolution has diminished the power of advertising and requires new skills in the marketing group to successfully use Facebook, You Tube, Linked in, and Twitter. Buyers are now all-knowing thanks to Google and their Facebook friends and they can get excellent information on different brands and their worth. Companies have to make a basic decision: Should the marketing department basically remain a communication group (one P – Promotion), or a 4P group (Product, Price, Place and Promotion)? I am in favor of giving marketing more power to participate in the product development process, and pricing, and place (distribution decisions).

Could you elaborate on that?

I would go further. The ideal marketing department would be headed by someone with the mindset of Steve Jobs. The Chief Marketing Officer (CMO) would be responsible for identifying the best opportunities for the business for the next five years, calibrating the profitability of the different opportunities, and participating with the other senior officers to make the right choices. The marketing group should know more about what is happening in the marketplace and what is likely to happen over the next few years and therefore be in a position to visualise where the business should be going. I remember that some years ago, GE asked its appliance marketing group to anticipate what will be the size and activities in kitchens in the next five years. The marketers came up with a great number of new ideas, many of which GE Appliance implemented. So the basic choice is whether marketing should remain largely a “service” department dishing out communications or it should be a proactive marketing group helping the company identify its best future opportunities. I sometimes say that a company should have two marketing departments: a large one that is busy selling what the company is making , and a smaller marketing group trying to figure out what the company ought to be making the in the coming years.

What is social marketing? Can you share some examples with us?

In July 1971, Professor Gerald Zaltman and I published “Social Marketing: An Approach to Planned Social Change” in the Journal of Marketing. The question was: “could you sell a cause the way we sell soap.” At the time, there was a lot of interest in how we could help people avert unwanted pregnancies, stop smoking, and say no to drugs. We could imagine creating ads that would change certain beliefs and behaviours. We could imagine making new products and services that would provide solutions in these problem areas. We could imagine distribution arrangements that would reduce the accessibility of unsalutory products or increase the availability of better substitute products and services. We could imagine using price to encourage or discourage certain behaviors. All four Ps would work on these social questions as they have worked in the commercial market.

And things have changed since then?

Since that time, social marketing has become another branch of marketing. There are over 2,000 social marketers operating in the world and addressing social causes of poverty and hunger, health, environment, education, littering, literacy and others. Social marketers don’t stop with advertising: they use a planning framework that applies the ideas of segmentation, targeting and positioning and the 4Ps to craft a workable social marketing plan. Dozens of social marketing examples are described in the 4th edition of Social Marketing that Nancy Lee and I published. There is now a hotline where social marketers interested in working on some social problem can put it out to other social marketers to learn of previous work and results in the same problem area. I believe that social marketing methodology has been a major contributor to the decline of smoking, the practice of birth control, the improvement of the environment, the providing of more health facilities and practitioners in poor countries, and rising rates of literacy.

Your basic training is as an economist. How did you move on to marketing?

Marketing is economics, even if many trained economists don’t recognise or read marketing and ignore the one hundred years of marketing writing. As I majored in economics at the University of Chicago (M.A.) and M.I.T. (Ph.D), I was impressed with the high level of theory but disappointed at the neglect of the real actions taking place in the marketplace. Classical economists didn’t say much about several key forces affecting demand such as sales force, advertising, sales promotion, and public relations. Economists focused mainly on price and how it affects demand and supply. They didn’t say much about distribution and the roles played by wholesalers, jobbers, retailers, agents, brokers and other transactional and facilitating forces. In fact, the first marketing books written around 1910 were written primarily by economists who wanted to bring the role of Promotion and Place into the understanding of markets. Even when economists discussed price, they rarely described how price is set separately by manufacturers, wholesalers, and retailers as price setting moves down the value chain.

So how did you move onto teaching marketing?

When I joined the Kellogg School of Management at Northwestern University, I was given a choice to teach either economics (macro or micro) or marketing. I chose marketing because it brought in all these additional forces that affect demand and supply. Earlier I was in a Ford Foundation program with Jerry McCarthy who was writing his textbook on Basic Marketing and proposing a 4P framework: Product, Price, Place, and Promotion. He was influenced by his professor of marketing at Northwestern University, Richard Clewett who taught Product, Price, Promotion and Distribution (which Jerry renamed Place to get the alliteration of 4Ps). Remember that the 4Ps are demand-shaping forces and should be part of basic economic theory. The interesting development today is that classical economics is undergoing the challenge of a different school of thought, namely behavioural economics. Behavioral economics drops the assumption that producers, middlemen and consumers always make rational decisions. At best there is “bounded rationality” and “satisficing” behavior rather than rational profit maximization. What is most interesting is that “behavioural economics” is just another name for “marketing” and what marketing has been researching for 100 years.

How do you manage to write about marketing from almost every angle?

I recognised early that marketing is a pervasive human activity that goes beyond just trying to sell goods and sales. What is courtship, after all, if not a marketing exercise? What is fundraising, if not a marketing exercise? What about building a stronger brand for your city, if not a marketing exercise? Every celebrity and many professionals are engaged in building and marketing their brand. This led me to want to bridge marketing theory and practice to other things than goods and services. I started to research and write on place marketing, person marketing, cultural areas marketing (museums and performing arts), cause marketing (i.e., social marketing), religious institution marketing, and so on.

(The interview originally appeared in the Daily News and Analysis on August 27,2012. http://www.dnaindia.com/analysis/interview_theory-of-maximising-shareholder-value-has-done-great-harm-to-businesses_1733089))

(Interviewer Kaul is a writer and can be reached at [email protected])

Chimpanzee Ai knows what zero means, but does Chidambaram?

Vivek Kaul

Tetsuor Matsuzawa is the director of the Primate Research Institute at Kyoto University in Japan. Among other things, Matsuzawa has taught a chimpanzee named ‘Ai’ to recognize the number zero.

As Alex Bellos writes in Alex’s Adventures in Numberland, “Ai had mastered the cardinality of the digits from 1 to 9…Matsuzawa then introduced the concept of zero. Ai picked up the cardinality of the symbol easily. Whenever a square appeared on the screen with nothing in it, she would tap the digit.”

So human beings are not the only ones to understand the concept of zero and what it means these days. Even chimpanzees do.

But one individual who does not seem to understand the concept of zero is Finance Minister P Chidambaram. He said on Friday that the government of India did not incur any losses by giving away coal blocks for free, while the Comptroller and Auditor General (CAG) of India put the losses at Rs 1,86,000 crore.

“If coal is not mined, where is the loss? The loss will only occur if coal is sold at a certain price or undervalued,” said Chidambaram. So what he essentially meant was that the government incurred zero losses by giving away the coal blocks for free.

Let’s go into some detail to try and understand why Chidambaram does not understand – or pretends he doesn’t – the concept of zero, his education credentials of having studied at Harvard Business School (HBS) notwithstanding. But then, even George Bush studied at HBS.

Between 2004 and 2011, the government allocated 218 coal blocks to private sector and public sector companies (including ultra mega power projects). Of these, the major allocations were made between 2004 and 2009 with only two allocations being made in 2010 and 2011. Twenty-one allocations made during the period have since been cancelled.

“If coal is not mined, where is the loss? The loss will only occur if coal is sold at a certain price or undervalued,” said Chidambaram.

These coal blocks were given away for free. This was done in order to increase the total coal production in the country. The government-owned Coal India Ltd, which accounts for 80 percent of the total coal production in the country, hasn’t been able to produce enough to meet the growing energy needs of the country.

Between 1 April 2004 and 31 March 2012, the production of coal by Coal India has increased by just 65 million tonnes to 436 million tonnes. This means a growth of 2.3 percent per year on an average.

Hence, to increase the overall production, the government gave away coal blocks for free so that power plants, including captive plants, are not starved of coal.

The CAG put the losses on giving away these blocks at Rs 1,86,000 crore. They used a certain methodology to arrive at the figure. First and foremost the blocks given to the public sector companies were ignored while computing losses. Secondly, only open-cast mines were considered while calculating these losses, underground mines were ignored.

The coal that is available in a block is referred to as geological reserve. But due to various reasons, including those relating to safety, the entire coal cannot be mined. What can be mined is referred to as an extractable reserve. The extractable reserves of these blocks (after ignoring the public sector companies and the underground mines) came to around 6,282.5 million tonnes. The average benefit per tonne was estimated to be at Rs 295.41.

As Abhishek Tyagi and Rajesh Panjwani of CLSA write in a report dated 21 August 2012, “The average benefit per tonne has been arrived at by first, taking the difference between the average sale price (Rs 1,028.42) per tonne for all grades of CIL (Coal India Ltd) coal for 2010-11 and the average cost of production (Rs 583.01) per tonne for all grades of CIL coal for 2010-11. Secondly, as advised by the ministry of coal vide letter dated 15 March 2012, a further allowance of Rs 150 per tonne has been made for financing cost. Accordingly, the average benefit of Rs 295.41 per tonne has been applied to the extractable reserve of 6,282.5 million tonnes calculated as above.”

Using this very very conservative methodology the losses were calculated to be at Rs 1,85,591.33 crore (Rs 295.41 x 6,282.5million tonnes) by the CAG.

These coal blocks, after being handed over for free, have been producing very little coal. Guidelines issued by the coal ministry call for captive blocks to start production within 36 or 42 months. According to CAG, these blocks were producing around 34.64 million tonnes of coal as on 31 March 2011. This is minuscule in comparison to the extractable reserves of 6,282.5 million tonnes that these blocks are supposed to have.

The fact that there has been very little production of coal is what Chidamabaram was referring to when he said that if coal has not been mined, how can there be a loss?

But this is a specious argument to make and in no way takes away the fact that the government of India gave away coal blocks for free. The CAG needed a method to calculate the losses on account of this. And it went about it in the best possible way. It essentially assumed that if the government had sold the coal that could be extracted from these mines it would have made around Rs 1,86,000 crore. In fact, by not taking into account the blocks given to public sector companies and and the underground mines, CAG underestimated the quantum of the loss.

The CAG can be criticised for not taking the time value of money into account. But the moot point is that whatever the assumptions made to calculate the losses, the resulting number would have been very big. And that is something that the government cannot shy away from.

Chidambaram is basically trying to confuse us by mixing two issues here. One is the fact that the government gave away the blocks for free. And another is the inability of the companies who got these blocks to start mining coal. Just because these companies haven’t been able to mine coal doesn’t mean that the government of India did not face a loss by giving away the mines for free.

All this does not change the fact that between 2006 and 2009 the Congress-led UPA government gave away 146 coal blocks to private and public sector companies for free. These blocks had geological reserves amounting to a total of around 40 billion tonnes of coal.

The CAG, in its report, points out that India has geological reserves of coal amounting to around 286 billion tonnes. Of this nearly 40 billion tonnes, or nearly 14 per cent, was given away free.

If Chidambaram still feels this means zero losses, then I guess we will have to redefine the entire concept of zero and mathematics. And this, during a time when even chimpanzees have started understanding the concept of zero.

The article originally appeared on www.firstpost.com on August 25,2012. http://www.firstpost.com/business/chimpanzee-ai-knows-what-zero-means-but-does-chidambaram-430073.html

Vivek Kaul is a writer and can be reached at [email protected]

Why you shouldn’t write off the Tata Nano just yet

Vivek Kaul

A little over three years after it was first introduced Tata Nano is being widely touted as a flop. The car which was supposed to cause traffic jams all over India is not selling as much as it was expected to.

Between January and July this year 55,398 units of the car have been sold. This is 13.3% more than the number of units that were sold during the same period last year. So even though the numbers are looking better this year they are nowhere near the installed capacity that the Nano plant in Sanand in Gujarat has, as an earlier piece pointed out. (You can read the complete piece here).

Numbers of reasons are being pointed out for the Nano flop show. Let me discuss a few here. In the book The Little Black Book of Innovation Scott D Anthony, who is an innovation consultant, points out a conversation he had with a colleague in late 2009. ““Here’s a provocative perspective,” my colleague said in late 2009… “I think the Tata Nano is going to be a disappointment.”… So why was my colleague being so skeptical? “Look at it from a customer’s perspective,” he said. These people could already afford to pay twenty-five-hundred dollars (or around Rs 1 lakh as the Nano was expected to be priced initially) for a perfectly good used car. Instead they consciously chose the scooter.”

Ratan Tata had the idea to build a car like Nano when he saw a family of four struggling on a two-wheeler on a rainy night in Mumbai. But despite the safety hazards people still preferred a two wheeler to a Nano. “Why would consumers choose a scooter? It wasn’t that these people didn’t care about their family. Rather, they didn’t have the space to park a car, or they found scooters that fit into tiny gaps on India’ chaotic streets a much more convenient form of transformation,” writes Anthony.

Another major reason being pointed out for Nano’s failure is it’s positioning. As Rahul Shankar points out in a blog post titled “Why did the Tata Nano fail as a disruptive innovation?” “The Nano was essentially branded as the world’s cheapest car…The truth is that no one wants to own a car that is thought off as cheap. Very few people treat a car as just a machine that takes them from point A to point B. This is basically what the Nano has been reduced to. People want to brag about how awesome their car is and how it kicks their neighbor/friends car’s butt….The advertisements that I have seen for the Nano have unfortunately come off as bland and catering again to the theme of affordability.” (You can read the complete post here)

These are valid points that have been raised. Even Ratan Tata has admitted to mistakes having been made. “We never really got our act together…I don’t think we were adequately ready with an advertising campaign, a dealer network,” Tata remarked earlier this year.

But these reasons notwithstanding, it’s too early to write off the Nano. Nano is what innovation experts call a disruptive innovation. This term was coined by Harvard Business School professor Clayton Christensen. “A disruptive innovation is an innovation that transforms an existing market or creates a new one by introducing simplicity, convenience, accessibility and affordability,” is how Christensen defined disruptive innovation when I had interviewed him a few years back for the Daily News and Analysis (DNA).

An important thing with disruptive innovations is that they tend to work out over a period of time. As Christensen said “It is initially formed in a narrow foothold market that appears unattractive or inconsequential to industry incumbents.”

A great example is the Apple personal computer which took around a decade to establish itself. As Christensen put it “A great example is the Apple personal computer. The incumbent companies of the time were those like Digital Equipment Corporation (DEC) that made minicomputers, which were big machines that sold for lots of money and could handle very complex tasks. When the personal computer burst on the scene, it sold for significantly less money than the minicomputer did…the PC wasn’t as good as the minicomputer for the market as it existed at that time. Apple made a wise decision and first sold the personal computer as a toy for children. Over time Apple and the other PC companies improved the PC so it could handle more complicated tasks. And ultimately the PC has transformed the market by allowing many people to benefit from its simplicity, affordability, and convenience relative to the minicomputer.”

Given this any disruption does not come as an immediate shift. “Disruption rarely arrives as an abrupt shift in reality,” write Clayton Christensen, Michael B Horn and Curtis W Johnson in Disrupting Class —How Disruptive Innovation Will Change the Way the World Learns.

This is something that Nirmalya Kumar, a professor at the London Business School (LBS) agrees with. “What I know about is radical versus incremental innovation. The more radical the innovation is the longer the time customers take to adopt it. People think of Nesspresso as being as a great radical innovation, but what they don’t know is that for 20 years it did not sell a whole lot and then the sales went up in a spike,” Nirmalya Kumar had told me in an interview I did for the Economic Times. Nespresso is a cappuccino maker sold by Nestle.

Amazon, which started off as a bookseller is another great example of a disruptive innovation which took time to get settled in. Another great example from the field of cinema is the movie Sholay. The film was massacred by critics when it released on August 15,1975. As Anupama Chopra writes in Sholay: The Making of a Classic “Taking off on the title of the film, K.L.Almadi writing in the India Today called it a ‘dead ember’… Filmfare’s Bikram Singh wrote: ‘The major trouble with the film is the unsuccessful transplantation it attempts – grafting a western on the Indian milieu.”

The Indian audience had never seen anything like this before. And it thus took time to sink in. The film went onto become the biggest box office hit of all time.

What these examples tell us is that it is too early to write off the Nano, despite the fact that the initial planks on which it was sold are largely not true anymore. “A cheap car that’s not really cheap. A safe car whose safety has been questioned. A poor people’s car that poor people aren’t buying. That sounds like a failure, certainly. But really it’s not. It’s par for the course for almost every breakthrough innovation,” writes Matthew J. Eyring the president of Innosight, a strategy innovation consulting and investment firm, on the HBR blog network. (you can read the complete piece here). “In fact, I can think of only one example of a CEO who pre-announced an innovation that was going to change the world and actually delivered it. That’s Steve Jobs of course,” he adds.

Critics point out that a lot of assumptions that Nano’s initial strategy was built on are not turning out to be true. The two wheeler riders aren’t upgrading to the Nano as they were. It’s no longer as cheap as it was initially promised to be. And people are buying it more of as a second car rather than their main mode of transport. But this is again in line with the way breakthrough or disruptive innovations operate.

As Eyring puts it “There’s nothing unusual about a company having to adjust the price, the production process, the marketing, or even the market of a breakthrough offering. The Nano’s price changes, the new maintenance contract Tata is rolling out to assure buyers of quality, the test drives it’s introducing, the new smaller showrooms, and the new commercials — all widely discussed in the press — should not really be news.”

All these things are also happening with the Nano because Tata Motors went in for a full fledged launch of the car rather than a small one. As Nirmalya Kumar put it “When the product development is radical you always do a small launch. They did a huge launch for Nano. They should have done a smaller launch. With radical innovation you need to keep tinkering and figuring out what is it exactly that the customer wants. This is because with radical innovation pre market testing is not really relevant because the consumers are not good at telling you whether they will buy a radical new product because they have no conceptualisation.”

This is something that Godrej & Boyce did with the ChotuKool refrigeratior. “Long before most people had heard of the low-power fridge ChotuKool, Godrej & Boyce spent quite some time investigating people’s refrigeration needs, designing and redesigning the product, and redoing its distribution strategy, carefully, slowly, and quietly,” writes Eyring.

It would have helped if Tata Motors had followed a similar strategy with Nano. As Eyring points out “It might not have been easy, but had Tata piloted the Nano quietly, on a small scale, perhaps through a limited production run in a small city like Durgapur in West Bengal or Ranchi in Jharkand, its engineering, pricing, financing, and marketing might have been adjusted far from the limelight to suit the needs of an optimal target customer… the Nano might have made its debut to the wider world with less hype and greater effect. It might not have been a 1 lakh car or even an alternative to motorscooters. But when it first appeared in the mainstream, it would have been right product for the right price in the right market.”

So now the Nano has entered the tinkering phase. And as this goes along Tata Motors will figure out what works and what does not. And this may be totally different from the assumptions the company started out with.

What still doesn’t change is its low price, despite the fact that it never sold for Rs 1 lakh as it was initially expected to. As Nirmalya Kumar put it “That’s the real startling novelty of the product because there is no car available anywhere in the world for $5000.”

The article originally appeared on www.firstpost.com on August 24,2012. http://www.firstpost.com/business/why-you-shouldnt-write-off-the-tata-nano-just-yet-429044.html

(Vivek Kaul is a writer and can be reached at [email protected])