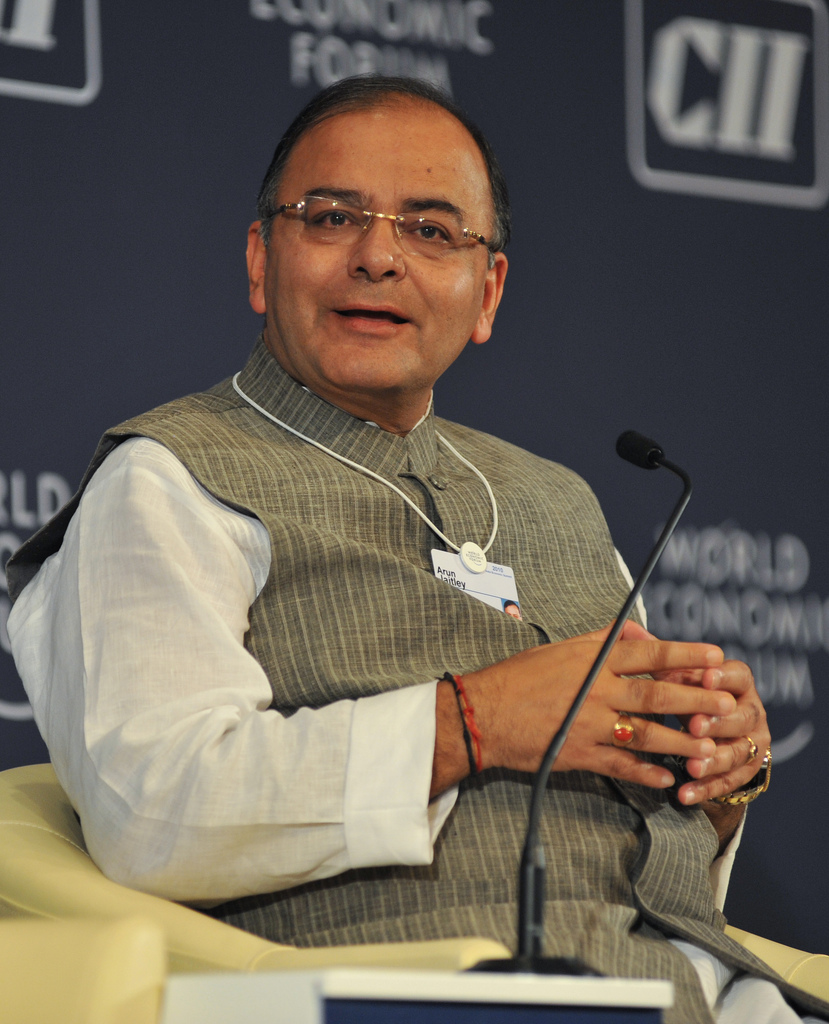

In the budget speech, the finance minister Arun Jaitely made in February 2017, he said: “Even 70 years after Independence, the country has not been able to evolve a transparent method of funding political parties which is vital to the system of free and fair elections.”

He further added: “An amendment is being proposed to the Reserve Bank of India Act to enable the issuance of electoral bonds in accordance with a scheme that the Government of India would frame in this regard. Under this scheme, a donor could purchase bonds from authorised banks against cheque and digital payments only. They shall be redeemable only in the designated account of a registered political party. These bonds will be redeemable within the prescribed time limit from issuance of bond.”

If one were to summarise the above two paragraphs what Jaitley basically said was that the government of India proposed to introduce electoral bonds to make transparent the method of funding political parties in India.

Eleven months later on January 2, 2018, the Narendra Modi government notified “the Scheme of Electoral Bonds to cleanse the system of political funding in the country.” The press release accompanying the decision listed out the various features of these bonds. They are:

1) Electoral bonds would be issued/purchased for any value, in multiples of Rs 1,000, Rs 10,000, Rs 1 lakh, Rs 10 lakh and Rs 1 crore, from specified branches of the State Bank of India (SBI).

2) The electoral bond would be a bearer instrument in the nature of a promissory note and an interest free banking instrument. A citizen of India or a body incorporated in India will be eligible to purchase the bond.

3) The purchaser would be allowed to buy electoral bonds only on due fulfilment of all the extant KYC norms and by making payment from a bank account.

4) It will not carry the name of payee.

5) Once these bonds are bought they will have a life of only 15 days. During this period, the bonds need to be donated to a political party registered under section 29A of the Representation of the Peoples Act, 1951 (43 of 1951) and which secured not less than one per cent of the votes polled in the last general election to the House of the People or a Legislative Assembly.

6) Once a political party receives these bonds, they can encash it only through a designated bank account with the authorised bank.

7) The electoral bonds shall be available for purchase for a period of 10 days each in the months of January, April, July and October, as may be specified by the central government. An additional period of 30 days shall be specified by the central government in the year of the general election to the House of People.

So far so good. There are a number of points that crop up here. Let’s discuss them one by one:

1) The finance minister Jaitley in his budget speech last year had talked about electoral bonds introducing transparency into political funding. These bonds will not have the name of the person buying the bond and donating it to a political party. The question is how do anonymity and transparency, not exactly synonyms, go together? This is something that Jaitley needs to explain.

2) The electoral bonds continue with the fundamental problem at the heart of political funding—the opacity to the electorate. With the KYC in place, the government will know who is donating money to which political party, but you and I, the citizens of this country, who elect the government, won’t. This basically means that crony capitalists who have been donating money to political parties for decades will continue to have a free run. The electoral bonds do nothing to break the unholy nexus between businessmen and politicians.

3) For these bonds to serve any purpose, they should have the name of the person buying the bond. And these names should be available in public domain, with the citizens of the country clearly knowing where are the political parties getting their funding from.

4) Supporters of the bonds have talked about the fact that anonymity is necessary or otherwise the government can crack down on those donating money to opposition parties. This is a very spurious argument. With the KYC in place, the State Bank of India will immediately know who is donating money to which political party. And you don’t need to be a rocket scientist to conclude that this information will flow from the bank to the ministry of finance. Hence, we will be in a situation where the government knows exactly who is donating money to which political party, but the opposition parties don’t. If the government of the day can know who is funding which political party, so should the citizens.

Now what stops the government (and by that, I mean any government and not just the current one) from going after the citizens or incorporated bodies for that matter, donating money to opposition parties. The logic of anonymity clearly does not work.

The structure of the electoral bonds seems to have been designed to choke the funding of opposition parties, more than anything else. Also, it is safe to say, given these reasons, cash donations will continue to be favoured by crony capitalists close to opposition parties.

5) There is one more point that needs to be made regarding political donations as a whole and not just the recently notified electoral bonds. Earlier the companies were allowed to donate only up to 7.5 per cent of their average net profit over the last three years, to political parties. They also had to declare the names of political parties they had made donations to. This was amended in March 2017. The companies can now donate any amount of money to any political party, without having to declare the name of the party.

To conclude, electoral bonds do not achieve the main purpose that they were supposed to achieve i.e. the transparency of political funding. All they do in their current form is to ensure that the ruling political party continues to consolidate its position, at the cost of the citizens of this country. Of course, given the marketing machinery they have in place, they will spin it differently. Given this, the WhatsApp wars on this issue have already begun.

The column was originally published in Equitymaster on January 5, 2018.