On February 28, 2017, the ministry of statistics and programme implementation published the Gross Domestic Product(GDP) growth figure for the three-month period between October and December 2016.

During the period the Indian economy grew by 7 per cent. This took most economists by surprise because they were expecting demonetisation to pull down economic growth. On November 8, 2016, the Prime Minister Narendra Modi had announced that come midnight the notes of Rs 500 and Rs 1,000 denomination, would no longer be money. Hence, the GDP growth for the period October to December 2016 was expected to be lower.

In one go 86.4 per cent of the currency in circulation was rendered useless. As Alain de Botton writes in The News—A User’s Manual: “Like blood to a human, money is to the state the constantly circulating, life-giving medium.”

When money is taken out of an economy, it stops functioning given that economic transactions come to a standstill. In the Indian case, cash/currency is the major form of money given that a bulk of transactions happen in cash. As per a PwC report 98 per cent of consumer payments by volume happens in cash. The Economic Survey of 2016-2017 points out: “The Watal Committee has recently estimated that cash accounts for about 78 percent of all consumer payments.”

In this scenario where bulk of consumer transactions happen in cash, the Indian economy for the period October to December 2016, should have come to a standstill. But the government data suggests that it grew by 7 per cent.

This seems unbelievable. The private consumption expenditure has grown by 10.1 per cent, the second fastest since June 2011. This when the retail loan growth of banks during October to December 2016, grew by just 0.5 per cent. The manufacturing sector grew by 8.3 per cent when bank credit to industry contracted by 2.8 per cent. Hence, there is something that is clearly not right about India’s GDP data.

Some analysts and experts have suggested that data is being fudged to show the government in good light. I really don’t buy that given that there is no evidence of the same. Having said that, one reason why the impact of demonetisation hasn’t been seen in the GDP growth figure is because the GDP calculations do not capture the informal sector well enough.

This is primarily because small manufacturers and those in the retail trade do not maintain accounts. Hence, estimates of the informal sector need to be made using the formal sector indicators. As the Economic Survey points out: “It is clear that recorded GDP growth in the second half of financial year 2017 will understate the overall impact because the most affected parts of the economy—informal and cash based—are either not captured in the national income accounts or to the extent they are, their measurement is based on formal sector indicators.”

In simple English, this basically means that the size of the informal sector while calculating the GDP is assumed to be a certain size of the formal sector. The formal sector has not been affected much due demonetisation. Hence, to that extent the size of the informal sector has been overstated in the GDP. It is expected that more information coming in by next year will set this right. This basically means that the GDP growth is likely to be revised downwards as more data comes in.

But this lack of dependable GDP data and other economic data creates its own set of problems for policymakers in particular.

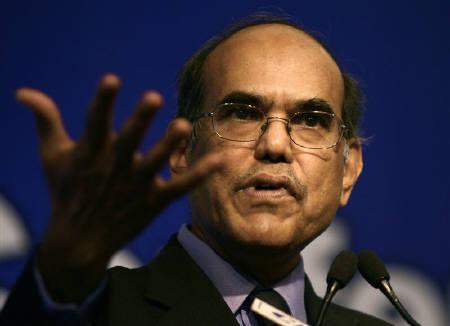

This is a point that former RBI governor D Subbarao makes in his book Who Moved my Interest Rate?. As he writes: “Our data on employment and wages, crucial to judging the health and dynamism of the economy, do not inspire confidence. Data on the index of industrial production(IIP) which gives an indication of the momentum of the industrial sector, are so volatile that no meaningful or reliable inference can be drawn. Data on the services sector activity, which has a share as high as 60 per cent in the GDP, are scanty.”

Further, this poor quality of data is frequently and significantly revised, making things even more difficult for policymakers. And this possibly led YV Reddy, Subbarao’s predecessor at the RBI, to quip: “Everywhere around the world, the future is uncertain; in India, even the past is uncertain.”

Long story short—sometime around this time next year, the GDP for October to December 2016, is likely to see a significant revision.

The column originally appeared in Daily News and Analysis (DNA) on March 9, 2017