In a little over a week, the Narendra Modi government will complete two years in office. The finance minister Arun Jaitley, has already started to give interviews in the media, highlighting the success of the Modi government on the economic front. The Vice Chairman of the NITI Aayog, Arvind Panagariya, has written columns around the same, as well.

What both of them haven’t really talked about is the oil price and its dramatic fall, during the time the Modi government has governed India. On May 26, 2014, the day Modi was sworn in as the prime minister, the price of Indian basket of crude oil was $ 108.05 per barrel. Nearly two years later, as on May 16, 2016, the price of the Indian basket of crude oil stood at $46.18 per barrel.

Interestingly, it even touched a low of $26.95 per barrel on February 12, earlier this year. This was a massive fall of 75%. The point being if this hadn’t happened, the finances of the Modi government would have gone for a toss totally. The petroleum subsidy number fell from Rs 92,000 crore in 2013-2014, to a little over Rs 60,000 crore in 2014-2015, to around Rs 30,000 crore in 2015-2016. For 2016-2017, around Rs 27,000 crore has been budgeted for the petroleum subsidy.

The government benefitted on two counts. First, it got a lower petroleum subsidy bill. Second, it captured a large part of this fall in oil price by increasing the excise duty on petrol and diesel. Between November 2014 and now, the excise duty on oil and petrol, has been increased nine times.

The total excise duty collected by the government on petrol and diesel in 2014-2015, had stood at around Rs 1,56,000 crore. This jumped by 59% to a little over Rs 2,48,200 crore in 2015-2016. Hence, lower oil prices were of huge benefit to the government. The state governments also cashed in by increasing the value added tax on petrol and diesel.

By doing this, the fall in the price of oil wasn’t passed on to the end consumers. The trouble is that now oil prices have started to go up again. Between February and mid-May, the price of the Indian basket for crude oil has gone up by more than 71%. As on May 16, 2016, it quoted at $46.18 per barrel.

In a scenario of falling oil prices, the government did not pass on the entire fall in oil prices to the end consumer. Hence, in a scenario of rising oil prices it shouldn’t pass on the entire increase to the end consumer as well by cutting down the excise duty on petrol and diesel. That will be a fair thing to do.

In an ideal world, the Modi government should have freed up the price of petrol and diesel totally, and let the international price of oil, decide the market price of petrol and diesel. If they had done that people would have adjusted to the idea of high oil prices, given that they would have seen low oil prices as well.

But that hasn’t turned out to be the case. The price of oil now is 57.3% lower than it was in May 2014. But the price of petrol and diesel has fallen by 17.4% and 12.9% only, in Mumbai.

Also, it is important to remember here that high oil prices can end up screwing the accounts of the government. This is simply because the government still subsidises the sale of cooking gas as well as kerosene oil.

Further, what does the government plan to do if oil prices continue to go up? If the government continues to raise petrol and diesel prices, I am sure there is going to be a public outcry.

This will happen simply because last time around when oil prices really went up, the end consumer did not have to pay for higher petrol and diesel prices. The oil marketing companies, the oil producing companies and the Manmohan Singh government bore the brunt of high oil prices. The consumer did not. This ended up screwing up the finances of the government.

Also, this time around the Modi government has benefitted tremendously from lower oil prices by raising excise duty on petrol and diesel. It had a tremendous opportunity to move towards a market driven price of petrol and diesel. But if it did that, it would have had to look for alternative sources of revenue.

It would no longer be possible for it to continue financing loss making public sector enterprises. This would mean that some ministers would have become totally jobless. It would have had to sell more shares in profitable public sector enterprises and so on. It would also have to look at ways for cutting down on frivolous expenditure that almost all governments indulge in. It would also have to sell its shares in the cigarette maker ITC, which it strangely continues to hang on to.

Of course, all these would have been difficult decisions and the government chose to latch on to the low hanging fruit of raising excise duty on petrol and diesel. A huge opportunity was missed out on.

Further, what is the government’s view on higher oil prices? As finance minister Arun Jaitley said in an interview to The Economic Times recently: “You see as far as the oil prices are concerned, this is one area where nobody has been able to predict, even reasonably what is going to happen. It is only after the event that people analyse what has happened. When the prices were close to a $120, nobody really thought that they will come down below 30. At 30, they said it would stabilise at 40, now it is 50.”

What Jaitley said was that oil prices cannot be predicted. This is a view that I have often maintained in the past. Nevertheless, after saying this, Jaitley went on to do exactly the opposite i.e. he tried to predict oil prices. As he said: “I think they are still range bound. And being range bound they are within the limits of what India can consider to be affordable and therefore unless there is some very alarming increase, which does not look likely at the moment, I think we are reasonably comfortable.”

So Jaitley feels that there are no chances of any alarming increase in oil prices. He said this after explaining in detail that no one can predict oil prices. This prediction came after oil prices have risen by 71% in a little over three months.

As Philip Tetlock and Dan Gardner write in Superforecasting—The Art and Science of Prediction: “Take the price of oil, long a graveyard topic for forecasting reputations. The number of factors that can drive the price up or down is huge—from frackers in the United States to jihadists in Libya to battery designers in Silicon Valley—and the number of factors that can influence those factors is even bigger.”

While, the government and those who run the government may not be able to predict oil prices, it is important that they think through what they plan to do if oil prices do continue to go up. This becomes especially important given that they did not pass on the fall in oil prices to the end consumer. Also, they are well and truly addicted to all the easy money coming in from raising the excise duty on petrol and diesel.

What is the Plan B of the Modi government? And more specifically, do they have one?

The column originally appeared in the Vivek Kaul Diary on May 18,2016

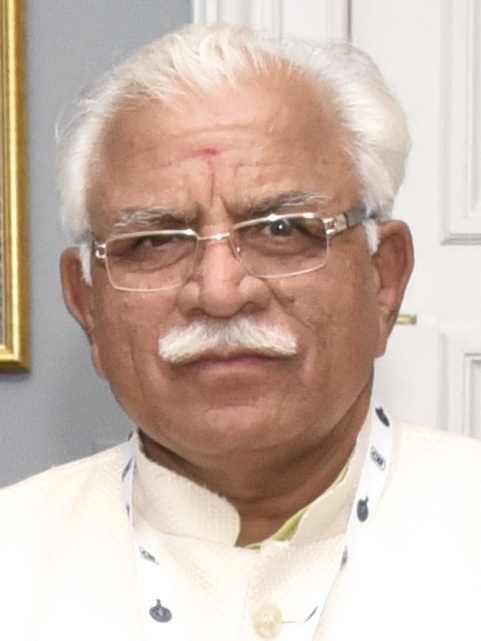

Last week, the government of Haryana notified the the Haryana Backward Classes (Reservation in Services and Admission in Educational Institutions) Act, 2016.

Last week, the government of Haryana notified the the Haryana Backward Classes (Reservation in Services and Admission in Educational Institutions) Act, 2016.