I normally don’t watch business news channels given that I find them quite flaky and get put off by their lack of depth. Nevertheless, these days with nothing better to do while having lunch, I sometimes do end up watching these channels discussing the vagaries and the volatility of the stock market.

And one of the things I have noticed is that the anchors as well as the stock market experts who offer their opinion on these channels speak with a lot of conviction and confidence. They appear to be in control of things. They appear to know what is happening, when the world around them is probably going crazy. We never hear them use words like probably, maybe or phrases like I don’t know. Further, they seem to have this uncanny ability to understand and explain something just as it has started to unravel. Their story telling abilities are simply terrific.

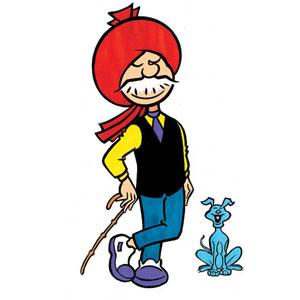

The uncanny ability of these anchors and experts to explain things at the speed of thought reminds me of a thought bubble in the Chacha Chaudhary comics, which used to say: “Chacha Chaudhary ka dimaag computer se bhi zyada tez chalta hai (Chacha Chaudhary’s mind works faster than a computer).” These anchors and experts are perhaps the Chacha Chaudharies of this day and age.

How is such speed possible? If the anchors and experts are so much in control and seem to have so much insight with such clarity, why are they not making money out of it? Why are they offering their advice for free on TV?

As the British economist John Kay writes in his new book Other People’s Money—Masters of the Universe or the Servants of the People?: “We deal with radical uncertainty through storytelling, by constructing narratives…The reality of market behaviour…relies on conviction narratives – stories that traders tell themselves, and reinforce in conversation with each other. Such narratives are the means by which we cope with radical uncertainty – the unknown unknowns that characterise… business and securities markets.”

The anchors and the experts appearing on business news television are in the business of telling us stories, which offer an explanation for why the market moved the way it did on a particular day. These days the most offered explanation is that economic jitters in China caused the stock market to fall. But this explanation is always offered after the stock market has fallen. No anchor or market expert ever says: “The stock market will fall today because there is economic trouble in China”.

As Kay writes: “The ‘explanations’ provided…by…market commentators…are little more than rationalisation of the noise generated by…market volatility.” And given this, it is worth asking that how useful is it for investors to listen to these explanations and make investment decisions after that.

Bob Swarup calls this phenomenon the illusion of explanation. He defines the term in his book Money Mania as: “Believing erroneously that your arguments…explain events.”

Further, how is it that the anchors and the market experts have an explanation for everything that happens in the stock market? And what is even more surprising is how they are able to come up with explanations so quickly. As John Allen Paulos writes in A Mathematician Plays the Stock Market: “Commentators…provide a neat post hoc explanation for every rally, every sell-off, and everything in between…Because so much information is available—business pages, companies’ annual reports, earnings expectations, alleged scandals, on-lines sites and commentary—something insightful can always be said.”

Over and above this there are many data releases which can also be used to come up with explanations. These data releases include inflation as measured by the consumer price index and the wholesale price index, index of industrial production, export and imports numbers, bank credit growth, and so on. And if all this does not fit into a convincing narrative you can always blame the Reserve Bank of India for not cutting interest rates.

Investing in specific stocks is not easy as it is made out to be by business news television. In fact, what anchors and market experts specialise in is making things simplistic rather than simple, given that they have limited time at disposal to say what they want to say. In this situation, where everything has to be said in thirty seconds to a minute, it is hardly surprising that things ultimately become simplistic. And this is clearly not good from an investor point of view.

What works for these anchors and experts is the fact that while coming up with explanations and predictions, their past record is not available for examination.

As Jason Zweig writes in Your Money and Your Brain: “Whenever some analyst brags on TV about making a good call, remember that pigs will fly before he will broadcast a full list of his past predictions, including the bloopers. Without that complete record of his market calls, there’s no way for you to tell whether he knows what he’s talking about.” This is a very important point that needs to be kept in mind when listening to anchors as well as experts on television.

Also, it is worth remembering here that which way a stock market will go is impossible to predict regularly on a day to day basis. Nassim Nicholas Taleb in his book The Black Swan—The Impact of the Highly Probable lists a certain category of experts who tend to be…not experts. In this list he includes economists, financial forecasters, finance professors and personal financial advisers.

As he writes: “Simply, things that move, and therefore require knowledge, do not usually have experts, while things that don’t move seem to have some experts. In others words, professions that deal with the future and base their studies on the nonrepeatable past have an expert problem…I am not saying that no one who deals with the future provides any valuable information…but rather that those who provide no tangible added value are generally dealing with the future.” Given this, the stock market experts clearly have an expert problem.

Hence, the next time you switch on your television to try and understand what is happening in the stock market, do remember all that has been pointed out above.

Happy investing!

The column originally appeared on The Daily Reckoning on September 25, 2015