For many years, the most widely used economics textbook all over the world was written by the American economist Paul Samuelson. Samuelson in different editions of his textbook maintained for a very long period of time that in the years to come the economy of the Soviet Union would grow bigger than that of the United States.

As Daniel Acemoglu and James A Robinson write in Why Nations Fail – The Origins of Power, Prosperity and Poverty: “The most widely used university textbook in economics, written by Nobel Prize-winner Paul Samuelson, repeatedly predicted the coming economic dominance of the Soviet Union. In the 1961 edition, Samuelson predicted that Soviet national income would overtake that of the United States possibly by 1984, but probably by 1997. In the 1980 edition there was little change in the analysis, though the two dates were delayed to 2002 and 2012.”

Of course nothing of this sort happened and the Soviet Union broke up in December 1991. But those were the days and the narrative of the success of the Soviet style of economics driven by five-year-plans was very popular. Samuelson was not the only one to be seduced by it. In fact, an entire generation was.

The trouble as Acemoglu and Robinson point out was: “In reality, what got implemented in Soviet Union had little to do with the five-year-plans, which were frequently revised and written or simply ignored. The development of industry took place on the basis of commands by Stalin and the Politburo, who changed their minds frequently and often completely revised their previous decisions.”

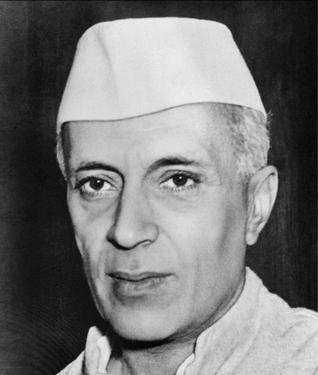

Closer to home, Jawaharlal Nehru was also a great fan of the Soviet style of economic development. So India had its own set of five-year-plans. The second five year plan (1956-1961) put into practice the idea of economic growth driven by public sector enterprises. Further, trained people were needed to run these public sector enterprises.

As PC Mahalanobis who was the Honorary Statistical Advisor to the government of India as well as the brain behind the second five year plan said in November 1954: “In dealing with the programme of industrial production one of the most important questions would be an adequate supply of trained personnel at all levels. This may indeed prove to be a serious bottleneck.”

In order to tackle this bottleneck the government moved its focus towards higher education. As Sanjeev Sanyal writes in The Indian Renaissance—India’s Rise After a Thousand Years of Decline: “Rather than invest in the general primary education, the country used up all its education budget to provide specialized personnel for grandiose public-sector-projects…The needs of the Mahalonobis model…meant that the country had invested heavily in tertiary education and built up a handful of world-class institutions.”

An impact of this, as Sanyal writes was that “the bulk of the country’s workforce was effectively not employable in anything other than subsistence agriculture.” And this is something which hasn’t really changed. Currently more than half of country’s population works in agriculture but contributes only around 18% of the gross domestic product (GDP).

This means there are many more people working in agriculture than there should be. If India needs to get its millions out of poverty, it is critical that other earning opportunities are created for these individuals. In fact, only 17% of the people who work on farms survive only on money they make from their farm. Everyone else does some extra work.

Hence, a bulk of these people need to be moved on to other jobs. The question is what kind of jobs they can really take on, given that many of them have very basic literacy skills or almost none at all. This pushes skilled or even semi-skilled jobs for that matter, out of the equation.

The point here being that the choice of a wrong economic model has had major consequences for India. And the sad part is that we still don’t seem to have learnt enough from the disaster of public sector driven development.

(Vivek Kaul is the author of the Easy Money trilogy. He tweets @kaul_vivek)

The column originally appeared in the Bangalore Mirror

on Sep 23, 2015