One of my favourite armchair theories is built around film critics and Salman Khan—the more the critics hate a Salman Khan movie, the more money the movie tends to make. It doesn’t work all the time, but it works often enough to at least be categorised as an armchair theory.

The superstar’s movies get regularly panned by film critics, and yet they end up making a lot of money. Now that doesn’t mean that the critics are wrong about what they think of Salman’s movies. They are actually quite trashy. An apt comparison are the movies that Amitabh Bachchan starred in the 1980s. Movies like Nastik, Mahaan, Pukar, Desh Premee, Mard, Coolie, Geraftaar, Jadugar and Toofan.

Most of these movies made a lot of money nevertheless they are completely unwatchable now, unless you are a die-hard fan to whom the quality of the movie doesn’t really matter. Bachchan’s bubble finally burst with Gangaa Jamunaa Saraswati, which I think is the trashiest film ever made.

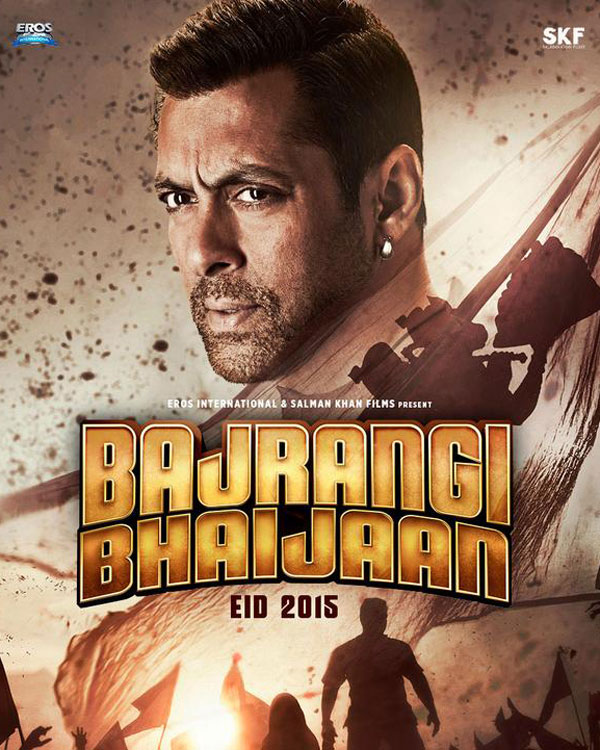

Khan’s bubble is still going strong and it was rather surprising that critics liked his latest film Bajrangi Bhaijaan. And these are not the trade critics whose reviews depend on what kind of business the movie they are reviewing is likely to do. These are critics who are genuinely in love with cinema. And they seem to have liked Bajrangi Bhaijaan and the movie has received a spate of ratings of 3 out of five stars.

So what were these guys smoking? How come so many film critics had nice things to say about a Salman Khan movie? Why have things changed this time around? The answer might perhaps lie in what economists call the contrast effect. Comparison comes naturally to human beings especially when they are making a decision. In such a situation, a particular option can be made to be look better by comparing it with something which is similar, but at the same time a worse alternative. This is known as the ‘contrast effect’.

As Barry Schwartz writes in The Paradox of Choice—Why More is Less: “If a person comes right out of a sauna and jumps into a swimming pool, the water in the pool feels really cold, because of the contrast between the water temperature and the temperature in the sauna. Jumping into the same pool after having just come indoors on a sub-zero winter day will produce sensations of warmth.”

This is the contrast effect and it best explains why film critics have fallen in love with Salman’s latest movie. How is that? Look at the movies Salman has starred in the recent past: Jai Ho, Kick, Dabanng 2, Bodyguard etc. Each one of these movies was pretty trashy. In comparison, Bajrangi Bhaijaan is a slightly better movie with some sort of a storyline and very good performances by the child artist Harshali Malhotra(who the audience has fallen in love with) and as well as Nawazuddin Siddiqui.

Hence, this contrast effect between the earlier movies of Salman and Bajrangi Bhaijaan has led to good reviews. In fact, a similar contrast effect was at work when Ek Tha Tiger had released in 2012. The movie was better than some of Salman’s earlier releases like Veer, Ready, London Dreams etc. And the critics had similarly given it good ratings.

There is another learning here. Bajrangi Bhaijaan has been breaking box-office records. As I write this, the movie has already made close to Rs 200 crore on the Indian box-office. Over and above Salman’s fans who watch every movie of his, however trashy it might be, the non-fans have also been streaming into the theatres because of the good reviews that the movie has universally received.

And what this tells us is that if Salman stars in even half decent movies they are likely to earn much more money than the trash that he chooses to star in. Hope he is reading this.

(Vivek Kaul is the author of the Easy Money trilogy. He can be reached at [email protected])

The column originally appeared in the Bangalore Mirror on July 29, 2015