Vivek Kaul

Vivek Kaul

One of the well kept secrets about the fragile state of the Indian economy is gradually coming out in the open. The Indian banks are not in great shape. The Financial Express reports that the chances of a lot of restructured loans never being repaid has gone up. It quotes R K Bansal, chairman of the corporate debt restructuring (CDR) cell, as saying that the rate of slippages could go up to 15% from the current levels of 10%. “The slower-than-expected economic recovery and delayed clearances for projects will result in a higher share of failed restructuring cases,” Bansal told the newspaper.

When a big borrower (usually a company) fails to repay a bank loan, the loan is not immediately declared to be a bad loan. The CDR cell is a facility available for banks to try and rescue the loan. Loans are usually restructured by extending the repayment period of the loan. This is done under the assumption that even though the borrower may not be in a position to repay the loan currently due to cash flow issues, chances are that in the future he may be in a better position to repay the loan. Or as John Maynard Keynes once famously said “If you owe your banka hundred pounds, you have a problem. But if you owe a million, it has.”

As of December 2013, the CDR cell had restructured loans of around Rs 2.9 lakh crore. Of this nearly 10% of the loans have turned into bad loans with promoters not paying up. Bansal expects this number to go up to 15%. Interestingly, a Reserve Bank of India (RBI) working group estimates that nearly 25-30% of the restructured loans may ultimately turn out to be bad loans.

And that is clearly a worrying sign. There is more data that backs this up. In the financial stability report released in December 2013, the RBI estimated that the average stressed asset ratio of the Indian banking system stood at 10.2% of the total assets of Indian banks as of September 2013. It stood at 9.2% of total assets at the end of March 2013.

The average stressed asset ratio is essentially the sum of gross non performing assets plus restructured loans divided by the total assets held by the Indian banking system. What this means in simple English is that for every Rs 100 given by Indian banks as a loan(a loan is an asset for a bank) nearly Rs 10.2 is in shaky territory. The borrower has either stopped to repay this loan or the loan has been restructured, where the borrower has been allowed easier terms to repay the loan (which also entails some loss for the bank).

The RBI financial stability report points out that this has happened because of bad credit appraisal by the banks during the boom period. “It is possible that boom period[2005-2008] credit disbursal was associated with less stringent credit appraisal, amongst various other factors that affected credit quality,” the report points out. Hence, borrowers who shouldn’t have got loans in the first place, also got loans, simply because the economy was booming, and bankers giving out loans felt that their loans would be repaid. But that hasn’t turned out to be the case.

Interestingly, Uday Kotak, Managing Director of Kotak Mahindra Bank recently told CNBC TV 18 that the current stressed, restructured or non performing loans amounted to nearly 25% of the Indian banking assets. He put the total number at Rs 10 lakh crore of the total loans of Rs 40 lakh crore given by the Indian banking system. This is a huge number.

Kotak further said that the Indian banking system may have to write off loans worth Rs 3.5-4 lakh crore over the next few years. When one takes into account the fact that the total networth of the Indian banking system is around Rs 8 lakh crore, one realizes that the situation is really precarious.

Interestingly, a few business sectors amount for a major portion of these troubled loans. As the RBI report on financial stability points out “There are five sectors, namely, Infrastructure, Iron & Steel, Textiles, Aviation and Mining which have high level of stressed advances. At system level, these five sectors together contribute around 24 percent of total advances of SCBs (scheduled commercial banks), and account for around 51 per cent of their total stressed advances.”

So, five sectors amount to nearly half of the troubled loans. If one looks at these sectors carefully, it doesn’t take much time to realize these are all sectors in which crony capitalism is rampant (the only exception probably being textiles).

Take the case of L Rajagopal of the Congress party (who recently used the pepper spray in the Parliament). He is the chairman and the founder of the Lanco group, which is into infrastructure and power sectors. As Shekhar Gupta pointed out in a recent article in The Indian Express, Rajagopal’s “company got a Rs 9,000 crore reprieve in a CDR (corporate debt restructuring) process just the other day. His bankrupt companies were given further loans of Rs 3,500 crore against an equity of just Rs 239 crore. Twenty-seven banks were involved in that bailout.”

Here is a company which hasn’t repaid loans of Rs 9,000 crore. It benefits from the restructuring of those loans and is then given further loans worth Rs 3,500 crore. So, if the Indian banking sector is in a mess, it is not surprising at all.

As bad loans mount, banks will go slow on giving out newer loans. They are also likely to charge higher rates of interest from those borrowers who are repaying the loans. This is not an ideal scenario for an economy which needs to grow at a very fast rate in order to pull out more and more of its people from poverty. If India has to go back to 8-9% rate of economic growth, its banks need to be in a situation where they should be able to continue to lend against good collateral.

So is there a way out of this mess? A suggestion on this front has come from Saurabh Mukherjea from Ambit. He suggests that the bad assets be taken off from the balance sheets of banks and these assets be moved to create a “bad bank”. This would allow the good banks to operate properly, without worrying about the bad loans on its books. As he writes “This would, in effect, nationalise the bad assets of the Indian banks and the taxpayer would have to bear the burden of these sub-standard loans.”

The government had followed this strategy to rescue Unit Trust of India (UTI). All the bad assets were moved to SUUTI (Specified Undertaking of the Unit Trust of India). The good assets were moved to the UTI Mutual Fund, which has flourished over the years. The government also has gained in the process.

The trouble here is that even if the government does this, there is no guarantee that it might be successful in reining in the crony capitalists. Over the last 10 years crony capitalists like Rajagopal, who are close to the Congress party, have benefited out of the Indian banking system. Given this, it is but natural to assume that after May 2014, the crony capitalists close to the next government (which in all likeliness will be led by Narendra Modi) will takeover. And that is the real problem of the Indian banking sector, for which there can be no solution other than a political will to clean up the system.

The article originally appeared on www.firstbiz.com on February 25, 2014

(Vivek Kaul is a writer. He tweets @kaul_vivek)

Month: February 2014

Post interim budget, the threat of a downgrade remains

Vivek Kaul

Vivek Kaul

On February 28, 2013, the finance minister P Chidambaram, presented the budget for the financial year 2013-2014 (April 2013 to March 2014). In this, he projected a fiscal deficit of Rs 5,42,499 crore or 4.8% of the gross domestic product (GDP). Fiscal deficit is the difference between what a government earns and what it spends, expressed as a percentage of the GDP.

All through the year, Chidambaram maintained that come what may the government won’t cross the fiscal deficit of 4.8% of the GDP. In the end he stood by his promise, but only on paper. The fiscal deficit for 2013-2014 is now estimated to be at Rs 5,24,439 crore or 4.6% of the GDP.

It was important that the government did not cross the target of 4.8% of the GDP that it had set, given the threat of a downgrade from international rating agencies.

The rating agency Standard and Poor’s (S&P) currently rates India as BBB-. This is rating is the lowest rating in the investment grade. If India were to be downgraded, its rating would fall to BB or the first stage of the junk status.

This would mean that a lot of foreign investors would have to sell out of the Indian bond market as well as the Indian stock market,given that they are not allowed to invest in countries with a junk rating. This would lead to huge pressure on the rupee as foreign investors cashing out will convert their rupees into dollars.

In fact, in November 2013, S&P had maintained the “negative” outlook on India. This meant that there were chances of a downgrade, over the next 12 months. As the rating agency had said in a release “The central government’s budget balance[i.e. the fiscal deficit], however, tells only part of the Indian fiscal story. Using a broader measure of general government deficits, we project a 7.2% of GDP deficit for fiscal 2014, to which one should add 1-2 percentage points of GDP deficits for the unprofitable portions of the consolidated public sector, including state electricity boards and oil-marketing companies.”

Keeping this definition of fiscal deficit in mind, how has the finance minister P Chidambaram done? It is safe to say that the fiscal deficit of 4.6% of the GDP is at best a hogwash. In order to arrive at that number, the finance minister has under-budgeted for petroleum, food and fertilizer subsidies in a major way. Estimates suggest that payment of more than Rs 1,20,000 crore worth of subsidies has been postponed to the next year.

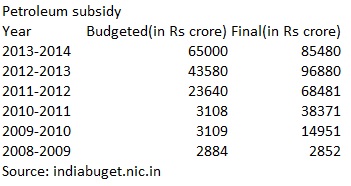

Take the case of petroleum subsidies. Chidambaram had budgeted Rs 65,000 crore towards it. The number has now been increased to Rs 85,480 crore. Of this amount, a substantial chunk has gone towards payments of petroleum subsidies that should have been paid in 2012-2013( April 2012 and March 2013) but were postponed to 2013-2014.

In fact, data released by the Ministry of Petroleum and Natural Gas in early February shows that the oil marketing companies have reported under-recoveries ofa total of Rs 1,00,632 crore during the first nine month of 2013-14 (April-December) on the sale of diesel, PDS Kerosene and cooking gas. Hence, the Rs 85,480 crore budgeted towards oil subsides is clearly not enough.

On the earnings side, Chidambaram has indulged in massive asset stripping to match his numbers. He has forced public sector banks, which are in a financially fragile state, to pay interim dividends of close to Rs 27,000 crore. ONGC and Oil India Ltd have been forced to pick up shares worth Rs 5,000 crore in the loss making Indian Oil Corporation, a company which no private investor wants to touch. And the government has also managed to get more than Rs 19,000 crore from Coal India, as dividend and dividend distribution tax.

Anyone who understands some basic accounting will tell you that using assets to pay for regular expenditure is never a great idea. Rating agencies like S&P obviously understand this. And that is why it had said in November 2013 that using broader measures, the fiscal deficit comes to greater than 7.2% of the GDP. In that sense, the deficit of the government is clearly greater than the 4.6% of the GDP that it has arrived at, once the accounting shenanigans are taken into account.

Given that, the threat of a downgrade remains. As S&P had said in November “we expect to review the rating on India after the next general elections when the new government has announced its policy agenda.” The agency plans to look at the fiscal policy of the next government as well, among other things. Given the mess the current fiscal policy is in, it will be very difficult for the next government to do much about it. The only way out is to slash government expenditure massively. And that is easier said than done.

The article originally appeared in the Daily News and Analysis (DNA) dated February 18, 2014

(Vivek Kaul is the author of Easy Money. He can be reached at [email protected])

How Chidambaram, UPA have turned India into a ponzi scheme

The Congress led United Progressive Alliance (UPA) government has turned India into a big Ponzi scheme. Allow me to explain.

Most governments all over the world spend more than they earn. This difference is referred to as the fiscal deficit and is financed through borrowing. Any government borrows by selling bonds. On these bonds a certain rate of interest is paid every year by the government to the investor who has bought these bonds.

The bonds also have a certain maturity period and once they mature the money invested in the bonds needs to be repaid by the government to the investor who had bought these bonds.

The trouble is that India has reached a stage where the sum of the interest that the government needs to pay on the existing bonds along with the money the government requires to repay the maturing bonds is greater than the value of fresh bonds being issued (which is equal to the value of the fiscal deficit).

Take the current financial year 2013-2014 (i.e. the period between April 2013 and March 2014). The interest to be paid on existing bonds amounts to Rs 3,80,067 crore. The amount that needs to be paid to investors who hold bonds that are maturing is Rs 1,63,200 crore. This total, referred to as the debt servicing cost, comes to Rs 5,43,267 crore (as can be seen in the following table).

The ratio of the debt servicing cost divided by fiscal deficit(referred to as the Ponzi ratio in the above table) for the year 2013-2014 comes to 1.04 (Rs 5,43,267 crore/ Rs 5,24,539 crore). What this means in simple English is that the government is issuing fresh bonds and raising money to repay maturing bonds as well as to pay interest on the existing bonds.

The ratio of the debt servicing cost divided by fiscal deficit(referred to as the Ponzi ratio in the above table) for the year 2013-2014 comes to 1.04 (Rs 5,43,267 crore/ Rs 5,24,539 crore). What this means in simple English is that the government is issuing fresh bonds and raising money to repay maturing bonds as well as to pay interest on the existing bonds.

This is akin to a Ponzi scheme, in which money brought in by new investors is used to redeem the payment that is due to existing investors. So investors buying new bonds issued by the government are providing it with money, to repay the older investors, whose interest is due and whose bonds are maturing. The Ponzi scheme runs till the money being brought in by the new investors is greater than the money being paid out by the existing investors.

In the Indian case, the Ponziness has gone up over the years. In 2009-2010, the Ponzi ratio was at 0.70. This means that money raised by 70% of the new bonds issued by the government went towards meeting the debt servicing cost. In 2013-2014, the Ponzi ratio touched 1.04. This means that the money raised through all the fresh bonds issued were used to pay for the interest on existing bonds and repay the maturing bonds.

In fact, the projection for 2014-2015 (i.e. the period between April 2014 and March 31, 2015) puts the Ponzi ratio at 1.28. This means that all the money collected through issuing fresh bonds will go towards debt servicing. But over and above that a certain portion of the government earnings will also go towards meeting the debt servicing cost.

The increasing level of the Ponzi ratio from 0.70 in 2009-2010 to 1.28 in 2014-2015, is a clear indication of the fiscal profligacy that the Congress led UPA government has indulged in over the last few years. This has led to a situation where the expenditure of the government has shot up much faster than its earnings. This difference has been financed by the government issuing more bonds. Now its gradually reached a stage wherein the government needs to issue more and more new bonds to pay interest on the existing bonds and repay the maturing bonds.

This is nothing but a giant Ponzi scheme. To unravel, this Ponzi scheme the next government will have to cut down on expenditure dramatically. At the same time it will have to look at various ways of increasing its earnings.

The article originally appeared on www.firstpost.com on February 18, 2014

(Vivek Kaul is a writer. He tweets @kaul_vivek)

Vote of account 2014: Is Chidu Mr Natwarlal of budgeting?

Vivek Kaul

Vivek Kaul

The finance minister P Chidambaram hasn’t crossed the “red line” of achieving a fiscal deficit target of 4.8% of the gross domestic product (GDP), that he had set for the government when he presented the last budget in February 2013. In fact, he has done even better and achieved a fiscal deficit of 4.6% of the GDP.

Fiscal deficit is the difference between what a government earns and what it spends, expressed as a percentage of the GDP. There are essentially three variables that are involved in calculating the number. The amount the government earns. The amount the government spends. These two numbers form the numerator and their difference is then expressed as a percentage of the GDP.

Hence, in order to achieve a targeted fiscal deficit, any of these three numbers can be manipulated. Chidambaram has worked on two of these three fronts to arrive at a fiscal deficit target of 4.6% of the GDP.

Let’s start on the expenditure front. The government expenditure is categorised into two kinds—planned and non planned. Planned expenditure is essentially money that goes towards creation of productive assets through schemes and programmes sponsored by the central government. Non-plan expenditure is an outcome of planned expenditure. For example, the government constructs a highway using money categorised as a planned expenditure. But the money that goes towards the maintenance of that highway is non-planned expenditure. Interest payments on debt, pensions, salaries, subsidies and maintenance expenditure are all non-plan expenditure.

As is obvious a lot of non-plan expenditure is largely regular expenditure that cannot be done away with. The government can at best delay paying subsidies. Hence, when expenditure needs to be cut, it is the asset creating planned expenditure which typically faces the axe and that is not good for the overall economy. If one looks at the numbers that is the direction they point towards.

The planned expenditure target of the government was at Rs 5,55,322 crore. The actual planned expenditure has come in at Rs 4,75,532 crore, which is close to Rs 80,000 crore or 14.4% lower. This as mentioned earlier is not a good sign.

If the government had incurred this expenditure the actual fiscal deficit would have come in at close to 5.3% of the GDP.

When it comes to non planned expenditure the target was at Rs 1,109,975 crore. It came in around 0.44% higher at Rs 1,114,902 crore. Most of the non-planned expenditure is regular in nature and hence, like planned expenditure, cannot be done away with. But there is one accounting trick that the government can resort to even on this front.

It can postpone the payment of petroleum, food and fertilizer subsidies to the next financial year. Let’s take the case of petroleum subsidies for one. Rs 65,000 crore had been allocated on this front. The actual amount spent by the government has come in at Rs 85,480 crore. Of this amount a major chunk has gone towards payment of under-recoveries from the financial year 2012-2013 (i.e. the period between April 2012 and March 2013).

Hence, the amount allocated is clearly not enough for the payment of petroleum subsidies. In fact, data from the Ministry of Petroleum and Natural Gas suggests that the oil marketing companies have reported under-recoveries of a total of Rs 1,00,632 crore during the first nine month of 2013-14 (April-December) on the sale of diesel, PDS Kerosene and cooking gas.

So clearly the amount of Rs 85,480 crore earmarked in the budget is not enough. This means that the payments that need to be made on this front have been postponed to the next year. A recent article in the Business Standard estimates that subsidies of around Rs 1,23,000 crore will be postponed to the next financial year.

These are subsidies on petroleum, food and fertilizer which should have been paid up by the government in this financial year, but will be postponed to the next financial year. The article points out that the government will need Rs 1,45,000 crore to pay up all the subsidies but is likely to sanction only around Rs 22,000 crore. This leaves a gap of Rs 1,23,000 crore which will be postponed to the next financial year, and will become a huge headache for the next government.

This essentially means that the government will not recognise expenditure when it incurs it, but only when it pays for that expenditure. This goes against the basic accounting principles, where an expenditure needs to be recognised during the period it is incurred.

Lets now look at what Chidambaram and the government have done on the government earnings front to boost that number. The government has indulged in massive asset stripping to boost its earnings. A recent estimate in the Mint newspaper suggests that since January 2014, public sector banks have announced interim dividends of Rs 27,474.4 crore.

These are banks in which the government had put in fresh capital of Rs 14,000 crore earlier in the year. So the government gives from one hand and takes away as much twice as more from another. Also, it is worth noting here that the public sector banks are currently on a very weak wicket. As Shekhar Gupta wrote in a recent column in The Indian Express “You read any of the recent data from the RBI, reputed market analysts and brokerages, economists, even from Uday Kotak on CNBC-TV18 this Thursday. You will know that the current stressed, restructured or non-performing loans in the Indian banking system amount to nearly 25 per cent of their total assets. Kotak put the aggregate at Rs 10 lakh crore out of total advances of Rs 40 lakh crore. Scared yet? He says the banks’ total write-offs over the next couple of years could be Rs 3.5-4 lakh crore. The total net worth of all banks now is about Rs 8 lakh crore. In other words, half their net worth will be wiped out.”

In trying to meet the fiscal deficit target, Chidambaram has further weakened the Indian banking system. And then there is the case of moving money from government owned companies to the government. Take the case of the Oil India Ltd and ONGC buying shares in Indian Oil Corporation worth Rs 5,000 crore, a company which is expected to lose a lot of money during the course of this financial year. Hence, no investor other than the government owned companies would have bought IOC stock.

Continuing with asset stripping, the 90% government owned Coal India Ltd, recently declared a record dividend in January of Rs 18,317.5 crore. Of this, the government will get Rs 16,485 crore, given that it owns 90% of the company. The government will also get Rs 3,100 crore, which Coal India will have to pay as dividend distribution tax. This money should actually have been used by Coal India to develop more coal mines so that India does not have to import coal, like it currently does, despite having massive coal reserves. But that of course, hasn’t happened.

The icing on the cake was the sale of telecom spectrum which made the government richer by more than Rs 61,000 crore.

It isn’t a good idea to meet regular expenditure by selling assets. How many people you know survived for long by selling their home, their car and other assets that they owned, to meet their daily expenditure? Ultimately to meet regular expenditure, regular income is needed. The sale of assets to meet current expenditure is not a great practice to follow. This is because assets once sold, cannot be re-sold.

If all these factors highlighted above are taken into account, there is no way the fiscal deficit would have come in at 4.6% of the GDP. The number is at best a joke that Chidambaram and his UPA colleagues have played on the citizens of this country.

The article originally appeared on www.firstpost.com on February 17, 2014.

(Vivek Kaul is a writer. He tweets @kaul_vivek)

How Chidambaram has screwed the next govt even before it takes over

Vivek Kaul

What we don’t achieve ourselves, we expect from others.

This is a statement I have oft used during family conversations in the context of the “unrealistic” expectations parents and grandparents have from their children and grandchildren.

But it is also true for the current Congress party led United Progressive Alliance (UPA) government. After spending much more than it earned for close to six years now, and managing to screw up the Indian economy left, right and centre, the Congress-led UPA government wants the government that takes over after the next Lok Sabha elections scheduled later this year, to cut down on the fiscal deficit.

The fiscal deficit target set for the financial year 2014-15 (i.e. the period between April 2014 and March 2015) is at 4.1 percent of the gross domestic product (GDP). Fiscal deficit is essentially the difference between what a government earns and what it spends expressed as a percentage of GDP.

The Congress led UPA government set a fiscal deficit target of Rs 1,33,287 crore or 2.5% of the GDP in the financial year 2008-09 (i.e. the period between April 2008 and March 2009). The actual number came in at Rs 3,36,992 crore or 6 percent of the GDP. And so started an era of fiscal profligacy.

The fiscal deficit target set for the financial year 2013-2014 (i.e. the period between April 2013 and March 2014) was set at Rs 5,42,499 crore or 4.8% of the GDP. But it is expected to come in at Rs 5,24,539 crore or 4.6% of the GDP.

This is primarily a result of accounting shenanigans as explained earlier and does not reflect the true state of the government accounts.

The fiscal deficit target set by the finance minister P Chidambaram for the next financial year is at Rs 5,28,631 crore or 4.1% of the GDP. Prima facie, the target is unachievable and there are several reasons for the same.

The petroleum subsidy allocated for 2014-15 stands at Rs 63,426.95 crore. In comparison, the petroleum subsidy for 2013-14 has come in at Rs 85,480 crore. This after, Rs 65,000 crore had been allocated towards it, at the beginning of the year.

Even a higher allocation of Rs 85,480 crore is not enough, given that the under-recoveries of the oil marketing companies for the first nine months of the year stand at Rs 1,00,632 crore during the first nine months of 2013-14 (April-December) on the sale of diesel, PDS Kerosene and cooking gas. The interesting bit here is that since 2009-10, the government has never been able to match the petroleum subsidy it allocated originally at the beginning of the year (as can be seen from the following table).

Take the case of 2012-13, when Rs 43,580 crore was allocated towards petroleum subsidy at the beginning of the year. The actual bill came in at close to Rs 96,880 crore, which was more than double. Given this, it is highly unlikely that Rs 63,426.95 crore will turn out to be enough.

This means greater expenditure for the government, and hence, a higher fiscal deficit, unless of course it balances the expenditure by cutting down asset creating planned expenditure. That is not the best strategy to follow, especially in a scenario of low economic growth which currently prevails.

Interestingly, even after making a higher allocation, a portion of subsidy payments is typically postponed to the next year. Estimates suggest that this year close to Rs 1,23,000 crore of subsidies have been postponed to the next year. The next finance minister would have to meet this expenditure.

If this expenditure has to be made and assuming that everything else stays equal, the fiscal deficit of the government would shoot to Rs 6,51,631 crore (Rs 5,28,631 crore + Rs 1,23,000 crore) or 5.1% of the GDP, against the currently assumed 4.1% of the GDP.

The only way the next finance minister would be able to meet the fiscal deficit target of 4.1% of the GDP, would be by following Chidambaram’s strategy of postponing expenditure, which is not the best way to go about it.

Another interesting point is the allocation of Rs 1,15,000 crore made towards food subsidies. Prima facie this does not seem to be enough to meet the commitments of the Food Security Act.

The government estimates suggest that food security will cost Rs 1,24,723 crore per year. But that is just one estimate. Andy Mukherjee, a columnist with Reuters, puts the cost at around $25 billion. The Commission for Agricultural Costs and Prices(CACP) of the Ministry of Agriculture in a research paper titled National Food Security Bill – Challenges and Options puts the cost of the food security scheme over a three year period at Rs 6,82,163 crore. During the first year (which 2014-15 more or less is) the cost to the government has been estimated at Rs 2,41,263 crore.

Economist Surjit Bhalla in a column in The Indian Express put the cost of the scheme at Rs 3,14,000 crore or around 3 percent of the gross domestic product (GDP). Ashok Kotwal, Milind Murugkar and Bharat Ramaswami challenge Bhalla’s calculation in a column in The Financial Express and write “the food subsidy bill should…come to around 1.35% of GDP.”

Even at 1.35 percent of the GDP, the cost of the food security scheme comes in at close to Rs 1,73,000 crore (1.35 percent of Rs 12,839,952 crore that Chidambaram has assumed as the GDP for 2014-2015).

All these numbers are more than the allocation of Rs 1,15,000 crore made by Chidambaram towards food subsidies. This means that there will be trouble for the next government in balancing the budget.

Of course, the new government that takes over after the Lok Sabha elections will present a fresh budget, in which it can junk all the calculations of the current budget (or to put it correctly, the vote of account). But even if the next government does that the expenditure commitments that the Congress-led UPA government has created are so huge, that it will be completely screwed on the finance front, even before it takes over.

This article originally appeared on www.FirstBiz.com on February 17, 2014

Vivek Kaul tweets @kaul_vivek