Vivek Kaul

Franklin D Roosevelt became the President of the United States in 1933, at the height of the Great Depression. Known for his no nonsense manner of speaking, Roosevelt is said to have remarked that “any government, like any family, can, for a year, spend a little more than it earns. But you know and I know that a continuation of that habit means the poorhouse.”

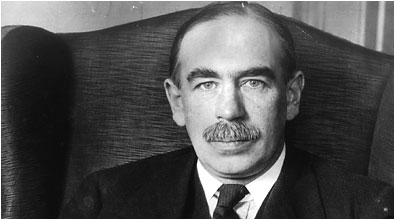

Those were the days when it was believed that governments should be balancing their budgets i.e. their income should be equal to their expenditure. Also, John Maynard Keynes, the most influential economist of the 20th century hadn’t gotten around to writing his magnum opus, The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money, till then. The book would be published in 1936.

In this book, Keynes introduced a concept called the “paradox of thrift”.

As Paul Samuelson, the first American to win a Nobel Prize in economics, wrote in an early edition of his bestselling textbook “It is a paradox because in kindergarten we are all taught that thrift is always a good thing….And now comes a new generation of alleged financial experts who seem to be telling us…that the old virtues may be modern sins.”

What Keynes said was that when it comes to thrift or saving, the economics of an individual differed from the economics of the system as a whole. An individual saving more by cutting down on expenditure made tremendous sense. But when a society as a whole starts to save more then there is a problem. This is primarily because what is expenditure for one person is an income for someone else. Hence, when expenditures start to go down, incomes start to go down as well. In this way the aggregate demand of a society as a whole falls, impeding economic growth.

Keynes used the “paradox of thrift” to explain the Great Depression. He felt that cutting interest rates to low levels would not tempt either consumers or businesses to borrow and spend. Cutting taxes, so as people have more to spend was one way out. But the best way out of a depression was the government spending more money, and becoming the “spender of the last resort”. Also, it did not matter if the government ended up running a fiscal deficit in doing so. Fiscal deficit is the difference between what a government earns and what it spends.

After the stock market crash in late October 1929 which started the Great Depression, people’s perception of the future changed and this led them to cutting down on their expenditure. In 1930, consumer durable expenditure in America fell by over 20% and residential housing expenditure fell by 40%. This continued for the next two years and the economy contracted, leading to huge unemployment.

As per Keynes, the way out of this situation was for someone to spend more. The citizens and the businesses were not willing to spend more given the state of the economy. So, the only way out of this situation was for the government to spend more on public works and other programmes. This would act as a stimulus and thus cure the recession.

In fact in his book Keynes even went to the extent of saying “If the Treasury(i.e. The government) were to fill old bottles with banknotes, bury them at suitable depths in disused coalmines which are then filled up to the surface with town rubbish, and leave it to private enterprise on well-tried principles of laissez-faire to dig the notes up again…there need be no more unemployment and, with the help of the repercussions, the real income of the community, and its capital wealth also, would probably become a good deal greater than it actually is. It would, indeed, be more sensible to build houses and the like; but if there are political and practical difficulties in the way of this, the above would be better than nothing.”

In the later years this became famous as the “dig holes and fill them up” argument. During the time Keynes was expounding on his theory, it was already being practiced by Adolf Hitler, who had put 100,000 construction workers for the construction of Autobahn, a nationally coordinated motorway system in Germany, which was supposed to have no speed limits. Italy and Japan had also worked along similar lines.

Very soon Britain would end up doing what Keynes had been recommending. Great Britain had more or less done away with both its army and air force after the First World War. But the rise of Hitler led to a situation where massive defence capabilities had to be built in a very short period of time.

The Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain was in no position to raise taxes to finance the defence expenditure. What he did was instead borrow money from the public and by the time the Second World War started in 1939, the British fiscal deficit was already projected to be around £1billion.

The deficit spending which started to happen, even before the Second World War started, led to the British economy booming specially in south of England where ports and bases were being expanded and ammunition factories were being built.

This evidence left very little doubt in the minds of politicians, budding economists and people around the world that the economy worked like Keynes said it did. Keynesianism became the economic philosophy of the world for the next few decades.

Lest we come to the conclusion that Keynes was an advocate of government’s running fiscal deficits all the time, it needs to be clarified that his stated position was far from that. What Keynes believed in was that on an average the government budget should be balanced. This meant that during years of prosperity the governments should run budget surpluses. But when the environment was recessionary and things were not looking good, governments should spend more than what they earn and even run a fiscal deficit.

The politicians over the decades just took one part of Keynes’ argument and ran with it. The belief in running deficits in bad times became permanently etched in their minds. Meanwhile, they forgot that Keynes had also wanted them to run surpluses during good times.

So, the politicians ran deficits in good times and bigger deficits in bad times. This meant more and more borrowing. And that’s how the Western world ended up with all the debt, which has brought the world to the brink of an economic disaster. The way the ideas of Keynes have evovled, has cost the world dearly.

Keynes, of course, understood the power (or danger) of economic ideas and he wrote in The General Theory that “The ideas of economists and political philosophers, both when they are right and when they are wrong, are more powerful than is commonly understood. Indeed the world is ruled by little else. Practical men, who believe themselves to be quite exempt from any intellectual influence, are usually the slaves of some defunct economist.”

Now, only if he knew that a lot of practical men(read politicians) in the years to come would become the slaves of his ‘distorted’ ideas. The ghost of Keynes is still haunting us.

This column originally appeared in the Wealth Insight Magazine edition dated October 1, 2013

(Vivek Kaul is the author of Easy Money. He tweets @kaul_vivek)